Only. a Trailer Can Do It

Page 40

Page 41

Page 42

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

says F. W. Knight

Some of the Transport Tasks for which a Trailer or Semi-trailer is Particularly Suitable

JUST as the laws of libel and copyright impose restrictions on authorship, so. do the Construction and Use Regulations and the Road Traffic Act restrain trailer

manufacture. The trailer factory can produce standard or special machines as required; the varieties of " specials " are almost infinite in number, and both legal and technical aspects of design must be studied, often to a degree unsuspected by the uninitiated.

Take, for example, the question of loading heights. Oddly enough (as I pointed out in my previous article), although the law is harsh concerning width and length of vehicles, it is virtually silent about vertical dimensions. Possibly this is a calculated concession by the lawmakers to compensate for the great technical difficulties which frequently arise, but space does not permit me to examine the ways in which trailer design would be influenced if legislation controlling heights did exist.

It sometimes happens that an operator wants the normal loading height of a vehicle increased to line up • with his loading bay, or to tip over a barrier, but it is more often the case that he wants it reduced. Where goods are shifted in bulk from one depot to another, the use of -loading bays, fork-lift trucks and hoppers may make the loading height comparatively unimportant: For heavy plant and machinery, how a6 ever, or for goods delivered to sites, shops, houses, and other places where external mechanical aids are lacking, the loading height must be kept to a minimum.

This is one of the fields of transport where the trailer—and particularly the semi-trailer—really comes into its own, for even the built-in tailboard loader, increasingly popular and useful though it is, does not always provide the complete answer.

Low-loaders may roughly be divided into three groups: the stepframe, the drop-frame and the machinery-carrier. The step-frame is most frequently employed for miscellaneous loads where the maximum space is required, but where the intrusion of wheel-boxes into the deck is not acceptable. The stepped portion of the frame is carried flush over the top of the trailing axle tyres. This particular shape of frame is also gaining favour for container traffic, not so much because it is easier to load, but because it reduces the overall height for bridge clearance, takes up less space on a ship, and improves stability by lowering the centre of gravity.

The drop-frame is favoured by furniture removers and manufacturers. Complaints are sometimes made about the inconvenience of wheel-arch boxes in the body, and operators have been known to request that they be removed, without explaining how a two-foot loading height can be obtained whilst using a three-foot diameter tyre! This type is also successfully employed to provide miscellaneous services to outlying villages, and to open-air events. Mobile shops, libraries, display vans, canteens, ticket offices, post offices and banks are notable examples of this trend.

The machinery-carrier takes several forms in different parts of the world. In the U.S.A., the stepframe model with reinforced frame and thin, detachable deck-plates over the rear axle, is popular. The disadvantage of this type lies in handling and transporting the long ramps which are essential to obtain a reasonable loading gradient. Cranking the rear end of the frame some times provides a partial answer for suitable loads, as in the army Tank transporters, based on American design, which have been a familiar sight in recent years.

Other machinery-carriers, such as the self-loader, the tipping deck, and the detachable goose-neck, are frequently employed in special operations overseas, but in this country by far the most common method of handling heavy indivisible loads is by means of the detachable-axle machine, in which the trailer axle, or axles, are mounted behind the low platform or bed which carries the weight. Obviously, this platform must be kept as low as possible for stability and ease of loading, and to enable high loads to have clearance under bridges and overhead wires. On the other hand, there must be a frame of adequate depth and yet have enough clearance underneath to prevent it from fouling obstructions or " bellying " on hump-backed hills or bridges.

To reconcile these conflicting requirements, some heavy-duty trailers have built-in hydraulic equipment which enables the bed to be raised or lowered as the circumstances 'demand.

In the three types of low-loading operation described, a rigid vehicle either cannot do the job as-well as a trailer, or cannot do it at all. There are various reasons for this which were summarized in the first article of this series; manceuvrability, cost, operating conditions, may all be contributory factors, but also, and particularly in the case of the detachable-axle machine, physical characteristics such as the transmission of power to the road wheels may put the rigid truck at a severe disadvantage.

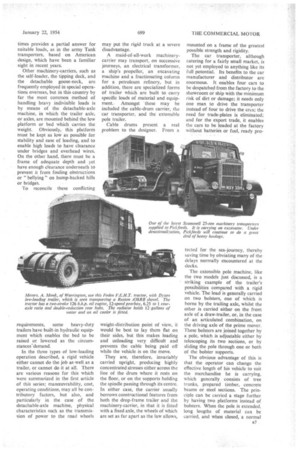

A maid-of-all-work machinerycarrier may transport, on successive journeys, an electrical transformer, a ship's propeller, an excavating machine and a fractionating column for a petroleum refinery, but in addition, there are specialized forms of trailer which are built to carry specific loads of material and equipment.Amongst these may be included the cable-drum carrier, the car transporter, and the extensible pole trailer.

Cable drums present a real problem to the designer. From a weight-distribution point of view, it would be best to lay them flat on their sides, but this makes loading and unloading very difficult and prevents the cable being paid off while the vehicle is on the move.

They are, therefore, invariably carried upright, producing highly concentrated stresses either across the line of the drum where it rests on the floor, or on the supports holding the spindle passing through its centre. In either case, the carrier usually borrows constructional features from both the drop-frame trailer and the machinery-carrier, in that it is fitted with a fixed axle, the wheels of which are set as far apart as the law allows, mounted on a frame of the greatest possible strength and rigidity.

The car transporter, although catering for a fairly small market, is not yet employed to anything like its full potential. Its benefits to the car manufacturer and distributor are enormous. It enables four cars to be despatched from the factory to the showroom or ship with the minimum risk of dirt or damage; it needs only one man to drive the transporter instead of four to drive the ens; the need for trade-plates is eliminated; and for the export trade, it enables the cars to be loaded at the factory without batteries or fuel, ready pro tected for the sea-journey, thereby saving time by obviating many of the delays normally encountered at the docks.

The extensible pole machine, like the two models just discussed, is a striking example of the trailer's possibilities compared with a rigid vehicle. The load is generally carried on two bolsters, one of which is borne by the trailing axle, whilst the other is carried either on the front axle of a draw-trailer, or, in the case of an articulated combination, on the driving axle of the prime mover. These bolsters are joined together by a pole, which is adjustable either by telescoping its two sections, or by sliding the pole through one or both of the bolster supports.

The obvious advantage of this is that the operator can change the effective length of his vehicle to suit the merchandise he is carrying, which generally consists of tree trunks, prepared timber, concrete beams or steel sections. The principle can be carried a stage further by having two platforms instead of bolsters. When the pole is extended, long lengths of material can be carried, and when closed, a normal type of goods-carrier is formed by joining the two platforms into one continuous body.

Another development has taken place which is especially suitable for long, rigid loads, such as largediameter oil pipes. The adjustable pole is omitted in this case, the pipes themselves forming the link between front and rear bolsters. Such models are so designed that, after the pipes have been delivered, the rear axleand-bolster assembly is hoisted picka-back on to its prime mover for the return journey to its base.

New Openings I have touched on only a few of the specialized forms of transport in which the trailer plays an indispensable part, but there is no doubt that there are many spheres of activity where its possibilities have not, as yet, been exploited or even explored. I firmly believe that the oil-engined tractor and semitrailer will be the principal goodscarrier of the immediate future. The word "immediate " is used advisedly, because it may only be decades before the atomic-powered helicopter becomes a commercial proposition.

One can only hope, however, that something will be done to improve our roads before that time comes.

The Government's road-construction programme, recently announced, recognizes the need for action, but indicates that although the spirit is willing, the Exchequer is weak. This penny-wise, pound-foolish attitude is rather like a man constantly spending money on corn plasters, instead of buying himself a larger pair of shoes to fit his swollen feet.

200 Tons by Road

Single pieces of equipment used in the electrical, petroleum and shipbuilding industries commonly weigh up to 200 tons, and these must often perforce travel by road. The cost of such journeys due to slow speeds, escort cars and lengthy detours is immeasurably higher than it need be if only, the state of our highways had not :Jagged so far behind the needs of modern commerce.

It is no exaggeration to say that there are several thousand different types of trailer in Great Britain today. Yet every post brings some new problem for the manufacturer to solve, necessitating either a modification to an existing model, or a com pletely new design. Rarely is he forced to confess "It can't be done." Far more likely is he to claim with some degree of pride: "Only a trailer can do it."

a8