What Britain owes to road transport

Page 14

Page 15

Page 16

Page 17

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

THIS YEAR Britain's manufacturing industries have more reason than usual to thank road transport. By maintaining supplies it has helped to keep the economy going, ensuring the flow of exports and imports.

And if the road transport industry had not been burdened with a number of over-zealous restrictions, many instigated by well-meaning but ill-informed legislators, it could have done more. However, rather late in the day it is being realised that manufacturers and vehicle operators can be relieved of some economic burdens without compromising environmental standards.

A House of Lords select committee, examining the complicated regulations on driving time, has concluded that they could be simpler, more flexible and have wider limits.

While it makes sense to guard against drivers' mistakes from tiredness, closer examination has always shown that safety is influenced more by the period between driving breaks and the total amount of rest obtained in a week than by the number of hours a day that a driver is at the wheel.

Eight hours was chosen by the Common Market as the daily driving limit because it matched a usual day's work in other industries (which do not, however, have overtime banned by statute). It was a social, not a safety, regulation.

The compromise between social and safety considerations now seems likely to include an overall limit on weekly or fortnightly driving time, but allowing nine or 10 hours' driving on odd days within that period. Such flexibility would be a big help to road transport's efficiency. The Common Market is reconsidering the issue.

The 38-tonne limit brought some benefits, but nothing like as many as could have been enjoyed by the nation if the upper weight limit had been the 44 tonnes recommended by Government's Armitage Inquiry at the end of 1980. Now 20 per cent fewer trucks would have been needed to deal with emergency movement of raw materials.

Political compromises do not alter economic truths. The fact remains that a vehicle with a gross weight capability of 44 tonnes is needed to handle 30tonne containers, without discharging part of the load inside them.

It was a waste of national resources to make the gross limit any less. Dimensionally, the heavy commercial vehicle is much the same, whatever its weight, but the average weight per axle is actually less at 44 tonnes; an extra axle spreading the load contributes to greater safety as well as reduced road damage.

Dimensional restrictions are also too restrictive. More goods -these days are distributed on standard sized 1 x 1.2-metre pallets. They can just be accommodated within the regulation 2.5m width, but many firms stipulate that foodstuffs are carried in insulated and refrigerated vans to make sure they are absolutely fresh. Thicker insulated walls diminish interior width to less than 2.4m.

Examples of insulated vans with walls only an inch thick were seen at the Birmingham Motor Show this year. Thin wall constructions do not so easily meet the Government's acceptance tests for temperature stability. The Institute of Road Transport Engineers wants the Government to raise the overall width limit to 2.53m. In Sweden and the USA the maximum width has already been increased to 2.6m.

This small concession of about an inch could make the difference between 22 and 24 pallets being accommodated in semi-trailers vans, already limited on height and length.

More enlightenment in public and political attitudes could be even more productive.

The industry does not quarrel with laws which are rationally based and protect the public interest. It does resent unfairness.

Taxation remains a burning issue. Rises this year were claimed to equate with roaddamage, but the tax scales remain wildly erratic. Only some types of commercials are taxed in line with the theoretical road damage factor proportional to the fourth power of axle weights.

For example, the 30.5-tonne eight-wheelers pay nearly 1.8 times as much tax as might be expected while 36 and 38-tonne tractive units with three-axle trailers pay nearly twice as much as they should. It is no consolation to operators of these vehicles that a 24-tonne artic with a single-axle trailer pays less than it should.

If damage is the criterion on which to base a tax structure, charges should be made according to the maximum weights at which the vehicle actually runs. Carriers of low density goods often come nowhere near the technical capability of their vehicle. A tax based on the licensed operating weight of the vehicle would be fair.

Despite the 20 per cent reduction in the legal driving time allowed, productivity has improved by 12 per cent in terms of ton-miles per vehicle, over the past 10 years. With a big swing to packaged produce, the volume of goods is also much greater.

Double shifting of drivers has increased the number of hours a vehicle spends on the road, and big investments in equipment have been made to speed deliveries and to reduce time spent loading and waiting.

A movement towards sliding door or curtainsided bodies and the fitment of electro-hydraulic lifting platforms cuts delivery time and improves access.

At the Motor Show examples of sliding doors were shown with special tracks that enable them to close flush with one another without infringing on floor width.

The trend towards lower load height continues with smaller wheels and the ultimate in low platforms provided by dropframe chassis.

Demount bodies carry the development of the low level truck one step further. Instead of waiting at the depot to be loaded, the vehicle can leave its body behind and pick up another, preloaded, within a few minutes.

Telescopic hydraulically operated legs can be lowered to the ground to give walk-in access for loading or unloading.

Unfortunately development of any good idea is now constrained by type approval. Alterations and conversions can be expensive under this bureaucratic retesting procedure further complicated by the secret nature of the original type-approval documentation.

This is particularly relevant to changes in the load-carrying capacity. Increasing payload capacity has been important in road transport's rise in productivity. Statistics make the economic sense of big-load capacity crystal clear. The number of trucks running at over 28 tonnes gross has settled down to about 95,000 over the past three years (six per cent of all commercial vehicles and half a per cent of Britain's whole vehicle population). Yet that small proportion carries 51 per cent of the freight tonnage that goes by road and accounts for 70 per cent of the ton-mileage.

Productivity is expected to continue to improve with the limit set at 38 tonnes. Although maximum weight vehicles cost around £45,000 a year to run, they carry each ton of load for 10 per cent less cost than do the 32.5-tonners, which themselves carry each of their 20 tonnes for less than half the cost of 16-tonner, but only with full loads. Vehicle selection must suit the maximum, not the usual, load they might be called on to carry.

Some solutions to providing maximum volume capacity were provided at this year's Motor Show in the form of close-coupled drawbar outfits. One example, with only a gap of 0.6m (2ft) between truck and trailer, affords over 15.5m (51ft) of total load length.

Using a Luton head is another way of gaining volume, but interior height can be maximised where small lowprofile tyres are fitted. The ultimate interior volume may be gained by slinging the drivers cab below the body but that is perhaps best left to futuristic designers.

The price to fit anti-collision guards, anti-spray equipment and noise insulation has been estimated to cost road transport operators at least £320 million over the next 10 years, or £500 more per unit, at 1984 prices.

These refinements, required by law, take no account of the equipment being fitted voluntarily. For instance, more than 30,000 heavy trucks and trailers are already equipped with anti-skid devices — more than in any other country in the world, at a typical cost of £500. Devices that might fall into the voluntary category include sonar tail-end transmitters to warn of anyone behind when a vehicle reverses. Good systems are being fitted at £300 a time.

Other electronic accessories which are increasingly specified include overload indicators and top-speed limiters costing from £200 upwards.

It is no longer unusual for £2,000 worth of extra equipment to be specified on larger machines — all in the cause of social acceptability.

No representative body of the industry has ever opposed legislation to make trucks more acceptable. However, there have been plenty of arguments about priorities, cost effectiveness and technical requirements. The £160 million estimated cost of fitting sideguards and rear bumpers could save about 700 lives over the next 10 years. The same amount spent on anti-skid equipment would save about 1,100 lives in the same period.

As for spray, unpleasant as it is, there are no statistics which reveal any attributable accidents. Yet fitment of the antispray mudguards proposed in a new draft law will cost at least £65 million. The road transport industry says it is in favour of anti-spray measures but wants the public to see visible improvement for the large investment involved.

Tests of the proposed equipment have indicated only a 10 per cent improvement at best; the industry wants to see at least 30 per cent reduction in spray — and believes that with more time and more flexibility in the wording of the law it could be done.

On noise the authorities are more understanding. Most new trucks and buses are already quieter than the minimum stipulated by law (86 decibels for light trucks and 88 for the powerful heavy ones). In only three years their noise has been halved. It will be halved again over the next three years. By 1987 no new truck will be allowed to be noisier than 84 decibels. The aim for about 1990 is 80 decibels — as quiet as today's cars.

Technically it is possible to achieve 80 decibels already, but at a cost of about £1,500 per vehicle and by adding a quarter of a ton to the unladen weight. There has to be a better way. Not least of the challenges is to make engines quieter in the first place.

The Government is helping with finance and research facilities, but at the same time has made the task harder. This year a change in the way nois.e is measured makes 88 decibels equivalent to 86 under the old rules. Operators say that financial incentives, such as vehicletax allowances already given by the Dutch Government, are needed to make the initial cost of noise suppression more acceptable.

Even before the last Budget, commercial vehicles paid, in taxation, more than one-and-ahalf times the whole country's current expenditure on roads. By comparison, the railways receive £1 billion in state subsidies. In return for substanial investment by specifying more acceptable vehicles for everyone the transport operator needs a little support, too.

Turbocharged six-litre diesel engines in trucks deliver over 200hp. Ten years ago it would have taken nine litres and more to do that — and with a great deal more noise. Since 1982 the power of many diesels has gone up by 20 per cent.

Current development work with ceramic-coated pistons and valves will produce further improvements.

For the time being, efforts are being concentrated towards getting as large a mass of air as possible into cylinders and burning the fuel efficiently. It is being done by new, fast-injection techniques in fuel systems and by turbocharging in conjunction with charge-cooling, but heat is a limiting factor.

At maximum weight power of about 350hp is becoming commonplace. Yet fuel eco

nomy is improving so that 38tonners use no more fuel than the 24-tonners did in the early 1960s. Not all the benefits are caused by engine design; atten

tion to streamlining and transmission efficiency, plus the development of tyres reducing rolling resistance have had ' their part to play.

In the past, extracting more power included raising the en

gine speed. Turbocharging changed that. In many cases, the speed has been reduced and the high-revving portion of the performance curves, where the fuel consumption starts to rise more steeply, is no longer used.

Slower revving engines matched to high-geared trans missions, is a recipe for fuel economy but presents problems at low road speed.

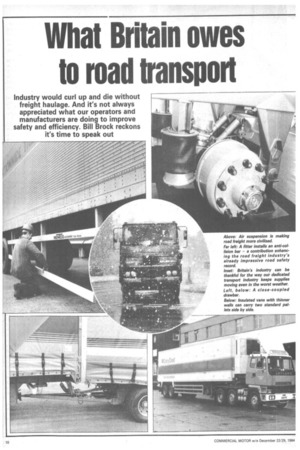

Low-speed pulling power has been improved by tuning the exhaust-gas flow to the turbocharger so that it keeps up the Air suspension on trailers is resulting in longer tyre life, reduced maintenance, better weight distribution over axles and quieter travel. boost at low engine speeds. It is helped further by tuning the length of the inlet manifold, so that a resonance pulse is generated over a selected narrow speed range to give an additional self-supercharge effect just where the turbocharger needs some assistance.

Pulse-resonance can adversely be used to spoil turbocharger performance at the top end, so limiting top-speed power.

A more positive method to restrict top-speed performance Is by fitting a road speed governor which works off the transmission and cuts off the fuel when a predetermined road speed is reached, but the power available for hIll-climbing or acceleration remains unrestricted. Average speeds are higher without the need to drive fast. Fuel economy is not impaired and traffic flow is improved for other road users.

Softer suspensions not only reduce impact damage to our roads and buildings, they im-prove vehicle roadholding, stability and braking.

This has not meant departing from the simple leaf-spring arrangement.

Instead, springs have been lengthened to make them more supple, and the number of leaves has been reduced. Often just one, tapering in thickness, is used, designed so that stress is constant over its whole length while eliminating friction encountered with multileaf de sign.

Results of further developments were seen at the Motor Show this October. Tapered-leaf springs, made out of strands of glass or carbon fibre, are encased in a strong plastics such as epoxy.

They are claimed to have better resilience yet with as much as 60 per cent weight saving. Pricing forecasts suggest they will not cost much more than steel springs.

Softer conventional springing will usually incur greater spring deflection leading to large differences between loaded and unloaded conditions, so making coupling of artics and loading of rigids chassis more difficult.

There is a cure; it is air suspension. Here, the springing is by rubber bags filled with air by the vehicle's compressed-air systems. A valve linking the chassis and axle keeps the distance between them constant. As load is removed, the valve lets air out of the springs.

When loaded, the valve feeds compressed air into the springs until the vehicle is level again. Whatever the load, the vehicle height remains constant.

Air springs automatically stiffen as more weight is applied so that the quality of ride stays the same whatever the load.

Air suspension is proving to be economic on trailers. Despite a greater initial capital outlay, subsequent pay-back comes in longer tyre life, reduced maintenance, better weight distribution over axles and quieter travel.