The Tramway's Decay.

Page 13

Page 14

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

By the Rt. Hon. Sir J. H. A. Macdonald, G.C.B., Member of the Road Board.

The time seems to have fully come for dealing with the tramway question in its entirety, and specially in its relation to omnibus traffic. In the past, much might be said, and justly said, in favour of the tramway system, as a public convenience in great cities and towns wherever the roadway was wide enough to admit Of the use of tramway cars without undue interference with the freedom of the way for other road users. At a time when cheap locomotion was provided for the community only in the form of slow horse traction, moving on rough, ill-kept causeways, and in small cramped omnibuses, the provision of a comparatively smooth-running surface by the laying of iron rails was not altogether unreasonable.

The Lead of Birkenhead and Liverpool.

When Francis Train succeeded in introducing a. tramway line into Birkenhead in the 'fifties of the 19th century, the revolution began. His road, consisting of ordinary railway rails and guard rails, was soon rejected on it merits. But the idea caught On. Very soon a system of tramways consisting of specially-grooved rails, and with small flanges on the wheels, was established in Liverpool and found public acceptance. This success Was followed up gradually, until to-day there are from 600 to 700 miles of tramroad in the United Kingdom.

The use of mechanical power by steam tractors on the tramlines was introduced in some places, and in others traction by cables worked by steam-power stations was adopted. But neither of these expedients was found satisfactory, and for nearly 30 years horse traction was practically dominant. It was so until the 'eighties of last century, when electric energy, cheap in quantity, became available, in consequence of installations for electric lighting being organized. Then tramways came to be electrically driven, horse and cable being gradually ousted.

Inconveniences Caused in Narrow Streets.

The pioneer in the electrification of tramways was Magnus Volk, whose tramcar ran back and forward along the shore below the Parade at Brighton, as to which one heard the cabmen on the cabstand above expressing themselves in strong language of their inability to conceive how the — it was done. From that time onwards the tramway attained a position of predominance, and found its way into many streets where any inconveniences which it caused were often forced by promoters and Parliament on the inhabitants, the preponderance of advantage to the public being considered to be in its favour. The tide of tramway success ran strong. Parliamentary sanction was given to hundreds of schemes. There seemed for a time to be no limit to the courage of promoters in demanding, or the complacency of committees in granting. Parliamentary sanction, even in cases where the establishment of a tramline involved a total disregard of important. public and private interests. Two instances may suffice--Coventry and Brentford. The restriction thought wise by the Board of Trade, by which a space of 9 ft. was prescribed as necessary between the tramline and the kerb, was passed by, and rails were permitted to be laid filling the roadway to within 3 ft. and sometimes 2 ft. of the pavement, so that no tradesman could load or unload his van without being constantly called upon to remove his vehicle to the other side of the street so as to allow the tramcars to pass, and no one driving and requiring to stop at a house or shop could do so without being hustled to one side when a tramcar was approaching, sounding its bell imperatively for the road vehicle go clear out of its way. It may be doubted whether, now, any such interference

with general traffic and the comfort and convenience of the general community would be sanctioned.

Bad Road Surfaces Gave First Encouragement.

The plating of tramway rails upon the public streets came to be permitted because the promoters were able to show that in the then existing state of the highways the surface& consisted of rough and uneven stone sett a or badly-laid macadam, which. made locomotion slow for the animal energy expended, involved expensiverunning owing to wear and tear on horses and vehicles, and caused jolting and discomfort to the traveller, who was carried at a slow speed to his destination. They were able to demonstrate that the haulage could be conducted more economically from the artificial surface provided for the wheels being free .from roughness, and that the running would not involve so much discomfort to the passenger as he had to suffer in the horsed omnibus. Tramways to produce easy and smooth running were not new devices. They were originally colliery expedient. Tram rails, not like those of to-day, but consisting of flat plates with inner flanges, were laid down for use by ordinary carts, to save the expense of road making and maintenance, in the haulage of coals from the pit head to the public road. They were in use many years before Francis Train, coming from the United States, where the streets and roads were as had as the worst in any civilized country, set the street-tramway ball rolling. Thus it was the bad road which gave the tramway its impetus to carry it into public favour. Had there been good, smooth, and durable surfaces and roads in the first half of the last century, it may well be doubted whether a proposal to lay down railways on public streets would have drawn capital from promoters, or have found favour with Parliamentary committeesIt certainly would not have found favour with the public.

Railways on Streets Are Now Superfluous.

The question has to be considered now in the light of the undoubted fact that the road of to-day in all populous places—in which alone tramways can be laid down profitably-can be made, and is being made, so as to give smooth running for ordinary vehicles with a minimum of noise. Anyone -who is as old as the writer can remember that the loud roar of the traffic—caused by the iron-tired wheels on the hard and inelastic surface of the street—was both by day and by night. He can recall living within a stone's throw of the Strand, in Buckingham Street, and when in bed, and waking at any hour up to 1 a.m. or after 6 a.m., hearing the rough, loud rumble of the traffic as the iron wheels ground their way, and the heavy, horses' shoes clattered over unevenness of the unyielding and often irregular causeway. The change to-day, although the volume of traffic has largely increased, is wonderful. The disturbers are not the vehicles, but the shrieking whistles, the nuisance from which one is glad to learn is being modified. Anyone can observe the contrast with the past general noisiness at places where the iron-tired road vehicle passes from the asphalt or wood pavement, or the modern road surface, such as that of the Thames Embankment, to the street which is still laid with granite setts. The change of sound is instantly observable, and the passenger at once feels the discomfort both of sound and jolting. The assertion may be made, without fear of candid contradietion, that roads are being rapidly provided, both in towns and elsewhere, by which smooth and easy running is spread over the whole breadth of the carriage-way, except where there are tramlines occupying the road

crown. Nose from cars is considerable and disagreeable.

, The tramway line was a concession to the public which suffered from a bad roadway. Re must be a very dogged tramway partisan, and blind—it may be -unconsciously—to the logic of facts and the signs of times who •would deny the proposition, that where road is smooth and the traffic runs over it easily and quietly, there is no call to place a railway upon • it, and to use vehicles which cannot run except on the filed line, laid down at very great capital outlay, and to a considerable degree monopolizing the roadway,, as against and to the inconvenience of all ordinary users of the road, with all the rumbling noise which is unavoidable when iron is driven over iron.

An Efficient Substitute is Found.

But the arguments against tramways were futile Until lately. . As long as an efficient substitute for the tramway did not present• itself, so long was it impossible to expect anything else than that more and more lines would be laid down regardless altogether of the rights and interests of the ordinary users of the highway, either for private or hired carriages or for commercial vehicles. But in the changed circumstanceswhich now present themselves, the question whether an efficient substitute has not been ,founcl, causing the raison d''are of the railway on the street to pass away, presents itself with emphasis. .Believing that it has been found, and that it is not only". an efficient substitute, but is -one_ which ,eliminates many disadvantages of the existing tramway System; both those -inherent and those which .affect other traffic, and further that it presents direct advantages which the tramline does not possess, it is proposed to consider street-passenger.traction from the present point of view. The tramway votary has :beer' • somewhat arrogant in his loudly-expressed assumption that his system was established in an im.pregnable,position, and would still go on conquering and to conquer. He harboured the thought that he could afford to pass by and even to sneer at, every ,argument in favour of any other mode of locomotion, whose votaries Were audacious enough to suggest that it could compete for the road with his, as he thought,

unassailable tramcar. • Many will remember the lofty utterance of Mr. Llewellyn Fell, the president of a society of tramway managers, at a banquet of the society, some

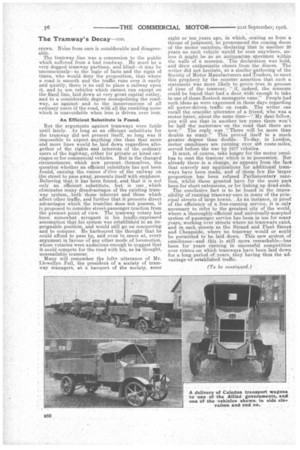

eight or ten years ago, in which, orating as from a throne of judgment, he pronounced the coming doom of 'the motor omnibus, 'declaring that in another 20 years no such vehicle wpuld be seen anywhere, unless it might be as an antiquarian specimen within the walls of a museum. The declaration was bold, and drew enthusiastic cheers from the diners. The writer did not hesitate, at a similar gathering of the Society of Motor Manufacturers and Traders, to meet this prophecy by the counter assertion that such a statement was more likely to prove true in process of time of the tramcar, if, indeed, the museum could be found that had a door wide enough to take in one of these Bostock menagerie vans." People had such ideas as were expressed in those days regarding aff power-driven traffic on roads. The writer can recall the oracular utterance of a friend, who was a motor hater, about the same time—" My dear fellow, you will see that in another ten years there won't be half the motorcars on the road that there are now." The reply was "There will be more than double as many.' This proved itself to a much greater degree than double. To-day, in London, motor omnibuses are running over 455 route-miles, served before the war by 3477 vehicles.

It must, of course, take longer for the motor omnibus to oust the tramcar which is in possession. But already there is a change, as appears from the fact that scarcely any applications for additional tramways have been made, and of these few the larger proportion has been refused Parliamentary sanction, whilst those granted have for the most part been for short extensions, or for linking up dead-ends.

The conclusive fact is to be found in the impossibility of running tramway. ears in many of the principal streets of large towns. As an instance, in proof of the efficiency of a free-running service it is only necessary to refer to the greatest city of 'the world, where a thoroughly-efficient • and universally-accepted system of passenger service has been in use for many years, working over streets where no tramways exist, and in such streets as the Strand and Fleet Street and Cheapside, where no tramway would or could be permitted to be laid down. This new system of omnibuses—and this is still more remarkable—has been for years running in successful competition over routes on which tramways have been laid down for a long period of years, they having thus the advantage of established traffic.