DELIVERING LORRIES BY CONVOY TO PERSIA.

Page 14

Page 15

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

An Authentic Account of the Trying Experiences of a Party of Drivers as Told by Two of Their Number.

AFEW months ago the Alimentation Department of the Persian Government ordered a fleet of 4-ton lorries from Leyland Motors, Ltd:, Leyland, Lancs., and a" number of British drivers was chosen by the makers to drive and deliver these vehicles to Teheran, Persia. Two of these men were Drivers A. J. Timms and E. Waterman, and we have received from them an interesting descriptive account of the journey and of some • of the incidents which took place en

route.

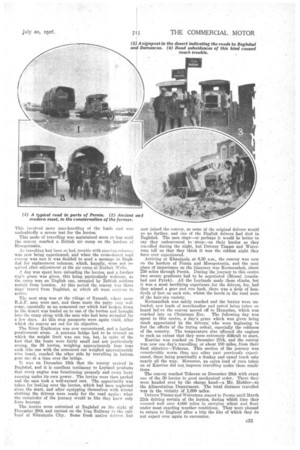

The drivers left England On October 26th of last year, and, after taking the overland route to Marseilles and crossing the 'Mediferriniein, arrived at Beirut, Syria, on. November 3rd, The machines had not then arrived, and after they were received it was found that there were twice as many lorries as drivers. As the vehicles were to be delivered in a batch it was necessary to obtain further drivers to deliver the surplus vehicles.

The new drivers, who were of many nationalities, were arranged for by the Nairn Transport Co., who run the crossdesert mail services. The party was fixed up with guides and escorts on account of the rebel trouble, which was very rampant at the time.

When the lorries were unshipped at Beirut they were filled up with petrol and everything _made ready for the start. During the sea passage a few of the vehicles had, unfortunately, been carried on the top deck and had been in contact with the salt-water during transit, with the result that they were somewhat difficult to start up. The vehicles were parked in the Socony Oil Co.'s premises, five miles outside the town, and, after securing the necessary equipment for a desert trip and loading them up with steel girders, which were to be delivered in the desert for the building of one of the air camp stations at Rutbah Wells, a start was made on what was to prove a noteworthy experience, especially as some of the native drivers had never driven a Leyland vehicle before.

The first day's trip took the convoy to Tripoli, a distance of Eibout 80 miles, where a halt was made for the night, the drivers sleeping on the vehicles. The fuel tanks were refilled overnight, but, as the convoy was about to move off in the morning, those in charge were informed that it could not do so owing to rebel activity along the line of route to be takcn.

The next port of call according to schedule was to be the city of Horns, which was under martial law at the time, but owing to the bad state of the route—i.e., deep mud, broken bridges, etc.—it was found possible to cover about only half the journey to a Freud' police post, and as night had now fallen it was decided to park the lorries until morning.

In spite of the difficult nature of the country, the like of which Drivers Timms and Waterman tell us they had never experienced before, the Leyland vehicles performed most creditably and gave,no trouble of any kind.

Hems was reached on the following day after a drive which could only be described as field punishment both to man and lorry. A consignment of wheat was taken on board some of the lorries in this city for delivery to the French Government authorities in Palmyra. This centre was reached after some bad travelling, when passports were vized : a halt was made here for a day and a half. The incidents which had been met sofar were triffirg compared with those yet to be experienced, for the convoy was now

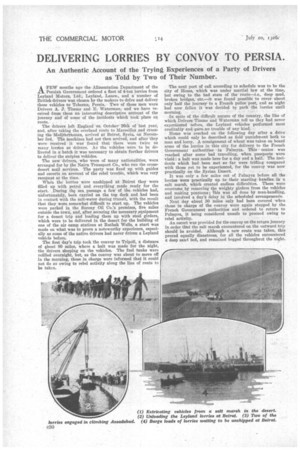

practically on the Syrian Desert. . It was only a few miles out of Palmyra before all the lorries were practieally Up to .their starting handles in a salt marsh, which created endless difficulties. These were overcome bY removing the weighty girders from the vehicles and making pontoons; this was all done by man-handling, and involved a day's delay in the scheduled arrangements.

Next day. about 30 miles only had been covered when those in charge of the convoy were again stopped by the French Government authorities and ordered to return to Palmyra, it being considered unsafe to proceed owing to rebel activity.

An escort was provided for the convoy on the return journey in order that the salt marsh encountered on the outward trip should be avoided. Although a new route was taken, this proved equally disastrous, for all the vehicles encountered a deep sand bed, and remained bogged throughout the night. This involved more man-handling of the loads and was undoubtedly a severe test for the lorries.

This mode of travelling was maintained more or less until the convoy reached a British air camp on the borders of Mesopotamia. • •

As travelling had been so bad, trouble with steerie g columns was now being experienced, and when the cross-desert mail convoy was met it was decided to send a message to Baghdad for replacement Columns, which, happily, were not required after adjustment at the air camp at Rutbah Wells.

A day was spent here unloading the lorries, and a further day's grace was given, this being particularly welcome. as the camp was an English one, occupied by British soldiers mainly from London. At this period the convoy was three days' trawd from Baghdad, at which all were anxious to a rrive.

The next stop was at the village of Ramadi, where more R.A.F. men were met, and these made the party very welcome, especially as an armoured car which had broken down in the desert was loaded on to one of the lorries and brought into the camp along with the men who had been stranded for a few days. At this stop passports were again vizor], after which the convoy set out for its objective.

The River Euphrates was now encountered, and a further predicament arose. A pontoon bridge had to be crossed on which the weight limit was one ton, but, in spite of the fact that the boats were fairly small and not particularly strong, the 30 lorries, weighing approximately four tons each. (the one with the armoured car weighed approximately nine tons), reached the other side by travelling in bottom gear 0113 at a time over the bridge.

It was on December 16th that the convoy arrived in Baghdad, and it is excellent testimony to Leyland products that every engine was functioning properly and every lorry running under its own power. The lorries were then parked and the men took a well-earned rest. The opportunity was taken for looking over the lorries, which had been neglected since the start, and after equipping themselves with winter clothing the drivers were ready for the road again ; what the remainder of the journey would be like they knew only from hearsay.

The lorries were entrained at Baghdad on the night of December 20th and carried on the Iraq Railway to the railhead of Khaniquin City. Some fresh native drivers had now joined the convoy, as some of the original drivers would go no farther, and one of the English drivers had died in Baghdad. The men slept—of perhaps it would be better to say they endeavoured to sleep—on their lorries as they travelled during the night, but Drivers Timms and Waterman tell us that they think it was the coldest night they have ever experienced.

Arriving at Khaniquin at 6.30 a.m., the convoy was now on the borders of Persia and Mesopotamia, and the next place of importance on the itinerary was Kermanshah, about 250 miles through Persia. During the journey to this centre two severe gradients had to be negotiated (Mount Assadabad and Pytak). All the Leylands made these climbs, but it was a most terrifying experience for the drivers, for, had they missed a gear and run back, there was a drop of hundreds of feet on each side, whilst the bends in the road were of the hair-pin variety.

Kermanshah was safely reached and the lorries were unleaded, new loads of merchandise and petrol being taken on board befare the convoy moved off to Hamadan, which was reached late on Christmas Eve. The followiug day was spent in this centre, a day's grace which was given being much appreciated by the drivers,* who were beginning to feel the effects of the trying ordeal, especially the coldness of the country. The temperature also affected the engines to such an extent that they were extremely difficult to start.

Kasvine was reached on December 27th, and the convoy was now one day's travelling, or about 100 miles, from their final objective—Teheran. This section of the journey was considerably worse than any other part previously experienced, there being practically a donkey and camel track only nearly all the way. Moreover, an extra load of corn taken on at Kasvine did nok improve travelling under these conditions.

The convoy reached Teheran on December 28th with every one of the 30 lorries in good mechanical order. There they were handed over by the charge hand—a Mr. Hodder—to the Alimentation Department. The total distance travelled was in the vicinity of 1,600 miles.

Drivers Timms and Waterman stayed in Persia until March 25th driving certain of the lorries, during which time they covered well over 4,000 miles in carrying wheat and flour under most exacting weather conditions. They were pleased to return to England after a trip the like of which they do not expect ever again to encounter.