Air braking systems on heavy vehicles haven't advanced much in

Page 46

Page 47

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

the past few decades. More trucks are being fitted with discs and ABS has become compulsory for heavier trucks and trailers, but the basic operating system has remained unchanged—until now. Truck manufacturers are looking at new ways to activate service brakes and, as with so many areas of truck technology, they are turning to electronics. Electronic braking systems (EBS) are quicker, better balanced and less complicated than conventional airtriggered systems. Will they become the industry standard? We've been taking a look at the latest developments.

The race is on to put the first production truck on the road with an electronic braking system. A Scania is already running with Bosch EBS on operational trials; the Lucas version should be on the road by the end of the year and the Bendix system is being developed in Germany following Bendbc's merger with Knorr-Bremse. But the smart money is on Mercedes-Benz and Wabco, who have had an EBS system under development for the past four years.

All well and good, but conservative hauliers, already suffering from technology overload, are liable to wonder if this is just one more gadget designed to make next year's trucks more complicated and more expensive. After all, current braking systems work perfectly well, so why change a good thing? In fact the driving force behind EBS is a laudable desire to reduce stopping distances: not by making the brakes more powerful, but by making them work faster. Quite simply, electricity moves faster than compressed air, and EBS reduces the delay between the pedal being pressed and the brakes doing their stuff.

Under current regulations air brakes have to be up to 75% of full power within 0.6sec of the driver's boot hitting the pedal.

Lucas says that EBS can reduce this brake lag to 0.15sec and that half-second improvement could be the difference between a near thing and disaster.

Fair enough, says Joe Soap Haulier—what's it all going to cost? For once it seems that new technology won't give manufacturers an excuse to bump up their prices because EBS avoids the duplication built into an ABS. equipped air braking system. Denis McCann, chief EBS engineer at Lucas, says his brief is to come up with an electronic system that costs no more than a conventional set-up with ABS and ASR.

Other braking system manufacturers won't commit themselves on pricing policy, but they agree with the principle.

Which brings us to Joe Soap Haulier's other complaint about new truck technology: it's more complicated. Not so, say the EBS designers; the new system is actually simpler. A single kit of parts will suit a number of different wheelbases and weights; only the electronic programming has to be changed for specific models. That's good news for chassis manufacturers, and operators are promised benefits too—such as less pipework to maintain, more even lining wear and improved tractor/trailer compatibility.

EBS is not yet a legal option simply because no one had heard of it when the relevant laws were drawn up, but the necessary paperwork should be drawn up within a few months.

So EBS is faster and simpler than a conventional system, it shouldn't force prices up and it will be available soon. That leaves our Joe with one more question: how does it work?

Two functions

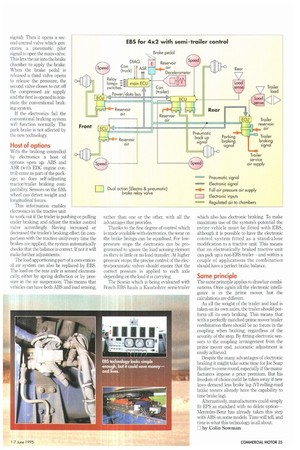

With EBS compressed air still powers the brakes and acts as a back-up if the electronics fail. There are no visible differences in the cab, but the traditional dual-circuit air-brake-system pedal is fitted with a potentiometer which tells the electronics when the driver has applied the brake and how hard. An electronic control unit then sends a signal to open an electropneumatic valve next to each wheel.

With the Lucas system the vehicle is running with the "normal" air braking system activated until the brake pedal is depressed. The first electronic signal cuts off the "normal" air supply at the valve next to the chamber (which has yet to be activated due to the inherent delay in the normal pneumatic pilot signal). Then it opens a second control valve which generates a pneumatic pilot signal to open the main valve. This lets the air into the brake chamber to apply the brake. When the brake pedal is released a third valve opens to release the pressure; the second valve closes to cut off the compressed air supply and the first is opened to reinstate the conventional braking system.

If the electronics fail the conventional braking system will function normally. The park brake is not affected by the new technology.

Host of options

With the braking controlled by electronics a host of options open up. ABS and ASR (with EDC engine control) come as part of the package; so does self-adjusting tractor/trailer braking compatibility. Sensors on the fifth wheel can detect weight and longitudinal forces.

This information enables electronics in the tractive unit to work out if the trailer is pushing or pulling under braking, and adjust the trailer control valve accordingly. Having increased or decreased the trailer's braking effort (in comparison with the tractive unit) every time the brakes are applied, the system automatically checks that the balance is correct. If not it will make further adjustments.

The load apportioning part of a conventional air system can also be replaced by EBS. The load on the rear axle is sensed electroni lly, either by spring deflection or by pressure in the air suspension. This means that vehicles can have both ABS and load sensing, rather than one or the other, with all the advantages that provides.

Thanks to the fine degree of control which is made available with electronics, the wear on the brake linings can be equalised. For lowpressure stops the electronics can be programmed to ignore the load sensing element as there is little or no load transfer. At higher pressure stops, the precise control of the electro/pneumatic valves should ensure that the correct pressure is applied to each axle depending on the load it is carrying.

The Scania which is being evaluated with Bosch EBS hauls a Kassbohrer semi-trailer which also has electronic braking. To make maximum use of the system's potential the entire vehicle must be fitted with EBS, although it is possible to have the electronic control system fitted as a stand-alone modification to a tractive unit. This means that an electronically braked tractive unit can pick up a non-EBS trailer--and within a couple of applications the combination should have a perfect brake balance.

Some principle

The same principle applies to drawbar combinations. Once again all the electronic intelligence is in the prime mover, but the calculations are different.

As all the weight of the trailer and load is taken on its own axles, the trailer should perform all its own braking. This means that with a perfectly matched prime mover/trailer combination there should be no forces in the coupling when braking, regardless of the severity of the stop. By fitting electronic sensors to the coupling arrangement from the prime mover end, automatic adjustment is easily achieved.

Despite the many advantages of electronic braking it might take some time for Joe Soap Haulier to come round, especially if the manufacturers impose a price premium. But his freedom of choice could be taken away if new laws demand less brake lag (VI rolling-road brake testers already have the capability to time brake lag).

Alternatively, manufacturers could simply fit EPS as standard with no delete option— Mercedes-Benz has already taken this step with ABS on some models. Time will tell, and time is what this technology is all about.

by Colin Sowman