Livestock Rates in Dispute

Page 100

Page 103

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

Solving the Charges. Laid Down by F.M.C. and Schedules

Problems of Recommended by ,R.H.A. Areas Examined : Some

the Carrier Rates Below Cost

pERHAPS the most interesting feature of livestock haulage is the agreement which has been reached in some areas on rates. Nevertheless, in other areas, hauliers are dissatisfied with the rates which the Fatstock

Marketing Corporation are offering. In particular, the carriage of pigs is the subject of controversy in some areas, whereas in others, agreement has been reached.

When the F.M.C. took over the marketing and transport arrangements for a proportion of the livestock in a free market, they accepted the former M.T.O.L. rates as a basis for charging. Lately, however, they have issued a schedule of rates on a new system. Although it is admitted that these rates are, perhaps, on the low side for the average livestock carrier's vehicle, according to the corporation's argument they show a reasonable return where a wagon can carry eight beasts or more. The answer, according to operators of experience, is that a larger vehicle would require a bigger return per mile than one that could carry only six beasts and, therefore, the rates are still low.

Pig haulage is in a class by itself and the average pig haulier is a specialist, separate from those who carry beasts and sheep, Most of them take their loads from the F.M.C. and, of course, accept the rates standardized by that body. They did so with a fair proportion of satisfaction until a new method of assessing rates was introduced. Now they are negotiating for the revision of that schedule.

These pig hauliers are so well established that in some areas they form a ring although not in the sense that rates arc agreed between them, because they are not. The principal difficulty comes in connection with operators outside that ring who have not previously carried pigs. Many of them are owner-drivers and they are inclined to pick and choose the days on which they will carry pigs.

For example, such an operator may be asked to pick up a load on, say, a Monday. He may reply that he is engaged on that day, but will deal with it on Tuesday, Wednesday or Thursday. That, of course, will not do in the haulage of livestock, when beasts, sheep or pigs. may have to be taken to a market on specific dates. It is that attitude which makes the " ring " reluctant to accept such operators as suitable for encouragement.

Before commenting on the several rate schedules which accompany this article, I must have a yardstick, which I take to be the operating cost of a typical livestock haulier's vehicle—a 6-7-tanner. 'Other sizes are employed on this work but the majority comes within the category specified.

The operating cost will be different from the average figures quoted in " ' The Commercial Motor' Tables of Operating Costs." The vehicle itself will be more expensive B50 than the average, which affects interest and depreciation. Bodywork may cost as much as £500.

One operator I know has the bodies of his vehicles made of solid mahogany. He has found that that wood is more resistant than any other to the acids coming from excreta. Bodywork is also liable to frequent damage from the animals, which means that maintenance costs will be above average.

Insurance premiums are higher than average, too. There is a little difficulty about the assessment of the Road Fund tax. If. for the purposes of the haulier's business, the body can be lifted off with its load, and this is sometimes done, the unladen weight for assessing the tax is that of the vehicle without the container.

If only the tax had to be considered, I think it would be worth while to pay the extra tax and have a fixed body. That, however, is not all. If, by using a container body and complying with the regulations, the unladen weight can be kept below the 3-ton limit, the vehicle can legally travel at 30 m.p.h., and that may be a matter for serious consideration. However. I shall take the tax to be £40 a year.

The following figures for cost of operation are arrived at by modifying the figures in the Tables, in accordance with my previous comments:— Standing charges per week: Tax, 16s.; levy, 3s. 11d.; wages, including provision for holidays with pay and employees' insurances, 163s. 7d.; garage rent, 10s.; insurance. 20s.; interest, 22s. 6d.; overheads, 60s.; total, £14 I6s. Running costs per mile: Fuel, 2.55d.; lubricants, 0.22d.; tyres, 1.72d.; maintenance, 2.44d.; depreciation, 4.37d.; total, 11.30d.

For a 300-mile week, the total cost will be £28 18s. 6d. and the cost per mile, Is, lid. (to the nearest penny). For a 400-mile week, the figures are £33 12s. 8d. and Is. 8d.; for 500 miles, £39 4s. and Is. 7d., and for 600 miles, £44 17s. and Is. 6d. There is provision in the case of the 500-mile and 600-mile figures for overtime payment. There is no provision for profit in any of these figures.

The next consideration is loading. I assume that the body will not be less than 20 ft. long, in which case the capacity will be 70 or 80 sheep, or 120 Iambs, or eight to ten head of cattle. The accommodation for loads of cows and calves or bulls or fat cattle, varies.

As further guidance in assessing loads, the following approximate figures for weights may be used, with some reservation:—Store cattle, 6-8-cwt. each; sheep, 40-45-1b.; lambs, about half the weight of sheep (over rather than under); a calf or pig, 80-90 lb, Here is a typical week's work, according to data supplied by a haulier. On one day, a load of 36 lambs and 30 calves was conveyed 54 miles, returning empty. On another day, 30 lambs and 33 calves were carried 120 miles, again returning empty. On the third day 44 calves were taken 94 miles and on the return journey 80 lambs were picked up and carried six miles.

The total mileage run by the vehicle during that week was 360. As the cost of operating a vehicle running 400 miles per week is Is. 8d. per mile we must, in this case, assume that the total expenditure was £30. If profit is calculated at 20 per cent., the revenue ought to be £36 and the rate per mile 2s.

To assess the revenue, the rate per beast, sheep, lamb and calf must be known. The accompanying tables show what the various areas of the Road Haulage Association have agreed shall be the standard of rates in the area: alternatively they are the F.M.C. rates.

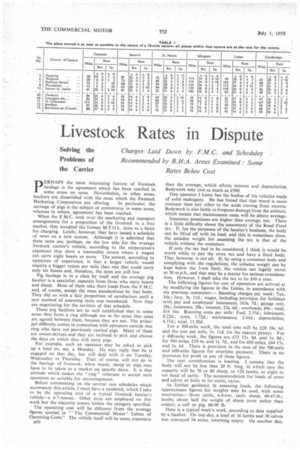

1 will take first the schedule issued by the Eastern area by the F.M.C., as it is most ingeniously contrived. It is based on zoning and the area is divided into squares numbered from I to 73. Each zone (10 miles square) is designatedas well as being numbered-by the town or village nearest its centre. In all places within that square, the rates are those applicable at the centre. Table 1 shows, first, the number of the square, and then its designating town or village.

Provision is made for traffic emanating from six towns in the areaCawston, Ipswich, St. Neots, Islington, Luton and Cambridge. Each of these places has a column to itself and in each is stated the lead mileage from the place named at the head of the column, the charge to make for the cartage of a beast and that for a sheep. In this area the rate for a beast is assumed to be about eight to ten times the rate for a sheep. Opinions differ on that point, as will be disclosed with reference to the other schedules.

To use the F.M.C. schedule the procedure is as follows:Assume that a livestock haulier living in Islington has the offer of a load of six beasts to be taken to Mundesley. (square 8). He refers to the table of rates and in the column headed " Islington " opposite the name Mundesley, he finds that the rate per beast is 38s. For six such beasts he must, therefore, charge El 1 8s.

Mundesley is 129 miles from Islington, so that the distance run by the vehicle in delivering this load is 258 miles.

Assuming that the vehicle is an oiler and that its average weekly mileage is 600, the charge should be Is. 6d. per mile, plus whatever profit is acceptable to the haulier. The cost of the 258-mile journey is £19 7s.-much more than the F.M.C. rate.

Table 2 is a schedule of rates agreed in the Northern Area of the R.H.A. The style is quite different from that of the F.M.C. schedule. Animals are differentiated in respect of rating by giving each type a number of units. A bull is rated at 44 points, a beast or boar at 22 and so on, as stated at the bottom of the schedule, which gives rates up to only 50 lead miles.

A good point is that there is provision for an extra charge per pick-up after the first. If a man goes for a load at one farm and at another under the same ownership, he roust charge for the total load, plus 5s. for having to stop and pick up at the second farm.

Table 3 is from the R.H.A. West Midland Area and is different again in its layout, as in its rates. It carries the lead distance up to 80 miles, but also makes provision for the calculation of the extra charge per mile run over that distance. That extra charge of 2s. 6d. per mile lead-only Is. 3d. per mile run-is, in my opinion, insufficient. However, it may be all that can be got and no doubt the compilers of the schedule are aware of that overriding condition.

It is of interest to note how to work out the rate to be charged for the first item in the week's work described above. First, 36 lambs (equal to three beasts at 19s. per beast) equals 57s.; 30 calves (equal to 7+ beasts at 19s. each), 143s.; total earnings, £10 for travelling 108 miles, or rather more than Is. lad. per mile, again falling short of what I regard as a minimum. Points to note about this schedule are the provision for a minimum charge, equivalent to that for six beasts; description of the method of calculating mileage; provision for an addition of 5s. extra per pick-up after the first and the method of calculating the load, according to the type of animal carried.

Credit must be given to the Western Area of the R.H.A. for the brevity of its schedule (Table 4). Here the table is based directly on mileage, the rate per mile varying with the load.

Table 5 reproduces an R.H.A. schedule from Yorkshire for carrying pigs, in which the minimum agreed load varies with the lead distance. S.T.R.