Braking with

Page 26

Page 27

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

Tradition

Jacobs Vehicle Systems, the well established US manufacturer of retarder systems, is in the vanguard of engine development with valve actuation technologies that could lead to diesel engines without camshafts...

It might seem a big leap from popping an exhaust valve for a retarder to operating the engine's valve train independently of the crankshaft, but for Jacobs Vehicle Systems it's by no means a leap in the dark. "We're building on a technology that we thoroughly understand," says vice-president of sales and marketing Scott Fowler. "Moving a valve to achieve engine retarder application is a core competency for Jacobs."

This is also a good time for Jacobs to develop products; as engine manufacturers seek to incorporate retarders into their designs, the market for the add-on engine brake is fast disappearing. Volvo's VEB, the Detroit Diesel/ Mercedes-Benz Series 55 DVB and MAN's EVB are all writing on the wall for Jacobs' future although the company has been through this before. In the mid1980s Jacobs' customers Cummins and Mack ventured into the engine brake business. Jacobs responded with better add-on brakes and eventually the engine manufacturers dropped their proprietary versions.

This time, however, Jambs is partnering rather than competing with the engine OEMs in the development of retarder technology and valve actuation systems. "Everyone's resources are scarce," says Fowler. "So, while Jacobs doesn't have capabilities that are unique, it has a proven competency and its focus on valve actuation can help customers develop their systems as appropriate."

Examples of this collaboration include Mack's E-Tech engines (see CM18-31 Dec) and Cummins' Signature 600. Both engines incorporateJake-designed engine brakes which perform significantly better than the previous add-ons, and Jacobs designs and manufactures components that go into the engines.

"The engine brake is fundamentally a function of valve movement. So when you control the valves, the exhaust brake comes for free," says Adish Jain, Jacobs' vice-president of engineering and quality. So the ultimate performance of the engine brake is assured by taking control of the valve train. And, says Jain, with North American emissions regulations placing a huge hurdle in front of engine designers for 2004, many are today looking at new technologies that will help them move to cleaner engines without massive trade-offs.

"Everyone understands 2004 [limits] and can make it with current technology," says Fowler. "But the loss in efficiency is significant. Everybody is looking for ways to minimise these trade-offs. The long range of product evolution will be part of the solution and advanced valve actuation is one technology available that will appear in around 2002."

Jacobs is increasingly becoming a partner in the development of new retarders and new engines. In the research and development area behind the office and manufacturing complex, enormous efforts have to be made to keep different engine prototypes separate from each other by walls, doors and screens as development teams from competing manufacturers concurrently work on the next generation engine platforms with Jacobs.

And the resources Jacobs brings to bear are impressive: there are more engine test cells than you'll find anywhere but inside an OEM's lab, an army of engineers with masters and doctorate degrees and 40 workstations running CAD software to back up the engine designers.

Because of its privileged relationships, Jacobs is obviously not saying what those platforms are. But chief engineer Jain hints broadly at what they will incorporate.

"In the short term these engines will deliver superior engine brake performance. It will he achieved using different valve actuation, such as the "lost motion" technique pioneered by Jacobs in the J-Tech brake for Mack. They will incorporate a dedicated cam for the brake, as in the Cummins engine. There will also be some "common rail" designs. The result will be better air management—more air in, and out at the right time. The short-term target will be to gain fastest release of compressed air for optimum retarding power.

"We shall also see increasing use of turbos with wastegates or variable geometry and there will be use of exhaust gas recirculation to boost retarder performance at all speeds (see CM 4-10 December 1997).

"ln the longer term, there will be full authority valve control allowing a combination of valve control and air management We plan to be the supplier of complete valve actuation systems, but we will introduce them incrementally. This helps manage the risk of getting out of mechanical systems and using electronics and hydraulics to drive the valves."

New technologies

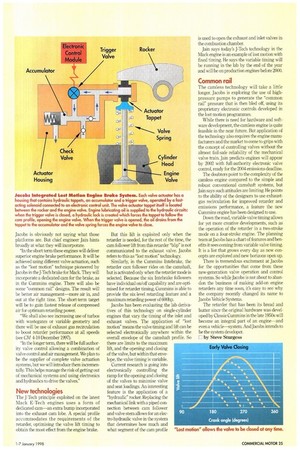

The .1-Tech principle exploited on the latest Mack E-Tech engines uses a form of dedicated cam—an extra bump incorporated into the exhaust cam lobe. A special profile accommodates the requirements of the retarder, optimising the valve lift timing to obtain the most effect from the engine brake. But this lift is exploited only when the retarder is needed, for the rest of the time, the cam follower lift from this retarder "blip" is not communicated to the exhaust valve. Jacobs refers to this as "lost motion" technology.

Similarly, in the Cummins Intebrake, the retarder cam follower rides on the camshaft, but is activated only when the retarder mode is selected. Because the six Intebrake followers have individual on/off capability and are optimised for retarder timing, Cummins is able to provide the six-level retarding feature and a maximum retarding power of 600hp.

Jacobs has been evaluating the lab derivatives of this technology on single-cylinder engines that vary the timing of the inlet and exhaust valves. The application of "lost motion" means the valve timing and lift can be selected electronically anywhere within the overall envelope of the camshaft profile. So there are limits to the maximum lift, and the opening and closing of the valve, but within that envelope, the valve timing is variable.

Current research is going into electronically controlling the ramp for the opening and closing of the valves to minimise valve and seat loadings. An interesting feature is the application of a "hydraulic" rocker. Replacing the mechanical link with a piped connection between cam follower and valve stem allows for an electro-hydraulic valve in the system that determines how much and what segment of the cam profile is used to open the exhaust and inlet valves in the combustion chamber.

Jam says today's J-Tech technology in the Mack engine is an example of lost motion with fixed timing. He says the variable timing will be running in the lab by the end of the year and will be on production engines before 2000.

Common rail

The camless technology will take a little longer. Jacobs is exploring the use of highpressure pumps to generate the "common rail" pressure that is then bled off, using its proprietary electronic controls developed in the lost-motion programmes.

While there is need for hardware and software development, the camless engine is quite feasible in the near future. But application of the technology also requires the engine manufacturers and the market to come to grips with the concept of controlling valves without the almost fail-safe reliability of the mechanical valve train. Jain predicts engines will appear by 2002 with full-authority electronic valve control, ready for the 2004 emissions deadline.

The doubters point to the complexity of the camless engine compared to the simple and robust conventional camshaft systems, but Jain says such attitudes are limiting. He points to the ability of the designers to use exhaustgas recirculation for improved retarder and emissions performance, a feature the new Cummins engine has been designed to use.

Down the road, variable valve timing allows for yet more creative developments, such as the operation of the retarder in a two-stroke mode on a four-stroke engine. The planning team at Jacobs has a chart of features and benefits it sees coming from variable valve timing. It is a list that grows every day as new concepts are explored and new horizons open up.

There is tremendous excitement at Jacobs for the opportunities that come from these new-generation valve operation and control systems. So while Jacobs is not about to abandon the business of making add-on engine retarders any time soon, it's easy to see why the company recently changed its name to Jacobs Vehicle Systems.

The retarder that has been its bread and butter since the original hardware was developed by Clessie Cummins in the late 1950s will become an integral part of an engine—and even a vehicle—system. And Jacobs intends to be the system developer.

D by Steve Sturgess