TRAFFIC PROBLEMS IN THE SECOND CITY.

Page 8

Page 9

Page 10

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

Glasgow's Tramways and Heavy Haulage Traffic. The Obstruction which each Occasions to the Other. The Value of the Steam Tractor.

ON MY FIRST morning in Glasgow our Citybound tramcar was held up by an obstruction which was obviously taking longer than usual to clear. Curious to see what it was, I walked forward and found a traction engine had fallen through the street. Its load, a 30-ton steel casting, hung perilously near the gaping breach. Below brawled alittle stream in flood—the prime cause of the trouble. A short length of the engine's funnel overlapped the tramway ever BO slightly, and there must have been 89 trams held up until it could be moved back 2 ins. !

In that little incident was crystallized the two leading features of road traffic in the Second City—its trams and its heavy engineering traffic. There is no -doubt that the trams are already seriously retarding the average speed of Glasgow traffic. The slightest, obstacle holds them up until it is removed. Stopping, as they do, at frequent halting places in the middle of an already narrow and congested street, they form a serious obstruction in themselves , the law which forbids motor traffic to pass stationary trams causes further obstruction, and, to crown all, encourages heedlessness on the part of the populace. Small wonder that the City's Cltief Constable said recently that the trams were his greatest traffic problem ; they take up too much-room in the streets.

Vulnerable, but Useful lo Glasgow's Millions.

" Why not, then," asks the casual visitor, "scrap this slow, old-fashioned system in favour of the faster, more readily manoeuvrable and generally more flexible motorbus '? " As well might one suggest scrapping the Corporation, or the Second City itself ! In Glasgow the question is not dismissed by a mere reference to the vast capital sunk in the Corporation

tramways enterprise, which amounts to £5,296,550, For the existing conditions the Glasgow system has many advantages possessed by no other at present evolved. • The chief of them CS cheapness, as epitomized in one of Glasgow's maw! nick-names, ""The City of the 'Ha'penny Tram." Artie happy state of :affairs indicated by this minimum fare lasted till 1920, and even now there is colistant dischssion of the possibility. of reviving it.) It is perfectly true that cheapness is not everything, that time also is money, and the gond burghers of Glasgow will come to realize it pretty sharply within the next decade or two. But, for the present, the extreme value for money offered by the Corporation tramways -is an untold boon to Glasgow's half-million industrial workers. For a penny fare, the average distance covered is 1.15 miles ; for I d, twice that distance. How many other transport systems in the world can carry a passenger 2.31 miles for three half-pence and show a handsome profit ? A twopenny fare takes one 3.44 miles, and for 2id. the distance is 4.63 miles, and thereafter the rate morks out at over two miles for a penny ! It is not surprising that business folk living away out in the suburbs find that a year's daily tram fares to the City are little if any more expensive than a railway season, whilst occasional travellers to places six and eight miles out will always choose "the calirs " when time is not of great importance.

This long-distance traffic is undoubtedly a big factor in making the trains pay. The average revenue per car-mile for the year ending May 31st last was 20.087d., whilst the expenses were 16.14Id. As a result, the sum of 220,000 of the profits was paid to the City's "common good "--the central reserve fund for social and civic emergencies, as the name implies.

A taxicab proprietor who brought a single ownerdriven hackney to Glasgow after the war and now has a flourishing business here told me 'was the almost universal stone paving of the streets was the feature of Glasgow which most impressed and annoyed him in the early days. Later, he learnt the reason, and his growing regard for the Second City and its industry and enterprise soon made him oblivious of skids and vibration. Truth to tell, there are very few bad spots in the streets considering the heavy traffic they have to bear.

Glasgow is first and foremost a centre of large-scale shipbuilding and heavy engineering ; not merely the heavy work connected with marine machinery, but locomotives, boilers for all purposes, constructional steelwork and even complete ships, which are built inland and transported in sections to the .works by road. Furthermore, a large proportion of the output is for export ; it is shipped direct from Glasgow to all parts of the world. The docks and the great shipyards are all on the west side of the -City ; most of the engineering shops and all the vast Clydeside steelworks are on the eastern side, adjacent to the fields of coal and iron which have given the city its industry. These are the conditions which set the local roadma,kers and menders a "nobler!' such as not even those of London have to cope with. Ever since the industrial revolution—in which it played a prominent part—the Second . City has had a severe task in keeping pace with the increasing size and weight of its heavy engineering products, and even now considerable damage is often done—sometimes to the extent of £2,000 in a single one of these nocturnal man

ceuvres. For, of course, all the heaviest of this work is done at night. -The team of traction engines—one is allowed per 30-40 tons to be hauled—proceeds to the starting point during the day. Loading up is performed in the afternoon, and. the long trek at 2 m.p.h. through the city begins

at midnight. The load is borne on a four or night-wheel bogie, which is so-called only by courtesy; the wheels do not swivel but are dragged round corners.

The bogie is built as low as possible, because of the height. of such loads as marine castings and boilers:, and the fear of fouling the overhead tram wires. It is constructed of heavy timber braced with steel plating, and with steel brackets at each corner. The axles are forged out of .solid steel ingots arid are usually 6 ins. or 7 ins, in diameter at the wheel boss. The tiny steel wheels have renewable bushes.

The use of wooden wheels has been urged by the Corporation, in defence of its roads, but it is doubtful whether, even with rein foreement, they would stand up to an axle loading of 80 or 40 tons. Special solid rubber tyres are still under consideration, but, unless the wheels were made to swivel, they would inevitably be torn off the rim at the first bend in the road, while to make them swivel the bogie "chassis" would have to be raised eonsiderably, and then the top of the load would not clear the overhead tram wires.

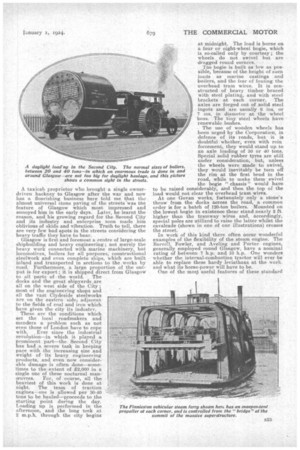

At one Govan works, fortunately only a stone's throw from the docks across the road, a common order is for a batch of 120-ton boilers. Mounted on the. lowest bogie in existence these stand nearly 2 ft. higher than the tramway wires and, accordingly, special poles are utilized to raise the latter whilst the cavalcade (shown in one of our illustrations) crosses the street.

In work of this kind there often occur wonderful examples of the flexibility of the steam engine. The Burrell, Fowler, and Aveling and Porter engines, generally employed round Glasgow, have a nominal rating of between 7 h.p. and 10 h.p. One wonders. whether the internal-combustion tractor will ever be able to replace these hardy leviathans at the work. and what its horse-power will have to be.

One of the -most useful features of these standard

traction engines is the steel cable and winch, which are often pressed into service in amusing emergencies. In the case of the road collapse mentioned in my opening paragraph, the fallen steed was raised by the help of another from the same stable. In many instances, where the shape of the cargo allows, and its weight and bulk demand, both loading and unloading are performed by this means. A. cylindrical boiler, for instance, is loaded on to its bogie by hitching the cable over the top and frankly rolling the thing up a built-up timber incline. To unload, two engines straddle the boiler and by hauling in and paying out, respectively, the monster cargo is lowered to the ground under perfect control. The ease with which the men in charge of these operations carry them out is, as is so often the case where skill is called for, much more apparent than real. The average onlooker, who, surveying the operation, would willingly claim to be able to do it as well himself, would make a terrible mess of it and only bring confusion to the scene.

Such manceuvres are even carried out on the road. The only approach to Greenock from Glasgow goes under a bridge which is too low for some of the boilers in demand locally. The procedure is to manoeuvre the boiler across the roadway, unload it in the manner described above, and roll it along the road beneath the bridge—under strict control, of course. The bogie is taken through separately and so placed that the boiler will rest on it in exactly the same position as before, and it is actually possible to calculate this to the inch.

Obviously, the business of heavy haulage contracting in and about the Second City is a highly specialized one. Some of the firms who engage in it—for instance, Messrs. William Kerr and Sons, one of the best known—have secured contracts for work of this kind in all parts of the United Kingdom, often when no local contractor would "look at" the task. The equipment of power stations in the Welsh mountains, and of steelworks in the flat country of Lincolnshire, and the haulage of giant marine castings from Newcastle to Liverpool are amongst the jobs undertaken south of the Border by the particular firm mentioned --and many an exciting and interesting tale they could relate.

A final difficulty to which I should refer is the lack of bridges across the Clyde. There is none at all below the centre of the City, and the only communication is by means of an assortment of ferries at intervals down to Old Kilpatrick. None of them is big enough to take seriously heavy loads such as I have described, but, for ordinary commercial and passenger traffic they serve almost as well as bridges could have done. And, unlike the latter, they allow the world's shipping, great and small, to use the channel and harbour which Glasgow has made for, herself in the last century. and which has contributed as much as any other factor to her industrial leadership—and to her street problems let it be added!