It's hard for haulage among the heather

Page 45

Page 46

Page 47

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

FEW Scottish farmers are becoming grain mountain millionaires. True, the dazzling yellow oil rape has made an appearance in recent years, but mainly in the fertile fields of Perthshire and the North East.

In the Western Highlands, life and farming go on much as before: this means a slow pace, difficult work and meagre rewards.

A thin layer of topsoil over granite alternates with squelching peat bogs and vast areas of forest. Crops are few and far between and, in many places, are grown virtually only for subsistence; all too often there is little to send to market.

It is sheep country. Hardy blackfaces daintily pick their way over rocky outcrops or mix it in the valleys with toughlooking cattle of indeterminate breeding.

It is hardly the most promising environment for road hauliers. But they, like the beasts they carry, have managed to survive — albeit with some difficulty.

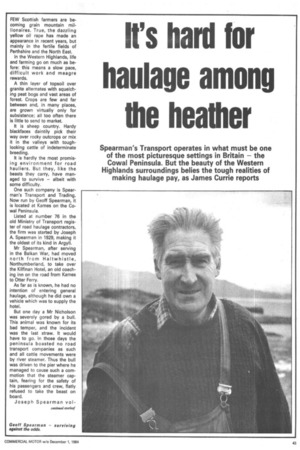

One such company is Spear man's Transport and Trading. Now run by Geoff Spearman, it is located at Kames on the Cowal Peninsula.

Listed at number 76 in the old Ministry of Transport register of road haulage contractors, the firm was started by Joseph A. Spearman in 1929, making it the oldest of its kind in Argyll.

Mr Spearman, after serving in the Balkan War, had moved north from Haltwhistle, Northumberland, to take over the Kilfinan Hotel, an old coaching inn on the road from Karnes to Otter Ferry.

As far as is known, he had no intention of entering general haulage, although he did own a vehicle which was to supply the hotel.

But one day a Mr Nicholson was severely gored by a bull. This animal was known for its bad temper, and the incident was the last straw. It would have to go. In those days the peninsula boasted no road transport companies as such and all cattle movements were by river steamer. Thus the bull was driven to the pier where he managed to cause such a commotion that the steamer captain, fearing for the safety of his passengers and crew, flatly refused to take the beast on board.

Joseph Spearman vol .antomd his !services, and the turceseful removel of the bull Orought other requests for his ielp. Spearman's! Troneport mad arrived, Originally listed es E. J. Spearmen (Joseph Sporran's initielel the company letef become Joseph A. Sellar Ma% The preeent title did not ionio into being until 105b.

Initial treffic centred around the movement of &Mock end the collection end delivery of mime' feedstuff. Progress wee steady rather than spectaculer, with diversification in 1937 when the coal merchant's buslnese of the late. Copt§In Andrew Turner was acquired,

This gave the transport busk nese its first real home = at Karnes Coal Pier, where coal was shipped In from Greenock by the old Clyde Cargo Shipping Company for the sum of fourpence per ton! Deliveries were fairly eubstentieh 80-70 tons it a time which was then bagged and sold for domestic wee at one and tenpence per hundredweight,

The coal carrier Itself became famous in her old age. She was the puffer Saxon liter to become the Vital Spark in the Pin Handy television Seriel.

Geoff Spearman was still a schoolboy, but he remembers with relish the times when he used to board a Steamer at TIghnabrualch, pay a penny, and trey& to the next pier et Auchenlochan, almost a mile away, in what had to be the cheapest sea cruise ever, It was after taking several such trips that he firet @Nounlured the hareh realities of business life. Shipping and road transport were locked in a fierce bottle for Custom and young Spearman, recognised by purser John McCallum as a son of the local transport operator, was cast Wore, his misery compounded by the delight of his schoolmates. In the end, however, the shipping companies lost out, they could not match the versatility or the cheaper rates offered by road transport and they finally foundered lust after the war,

Spearman's did some pruning of its own: the price of bringing In coal had risen to E1 per ton and this had to be purchased 150 tons at a time.

Out went the coal business and it was back to haulage on a full-time basis. The company moved from the Coal Pier to the nearby wharf which had

once served the gunpowder factory at Millhouee. This site overlooks what Is arguably the most picturesque stretch of water in Scotland. Racing yachts, N or 100 at a time, pass through in the summer end the Waver*, lest of the Clyde steamers, still directs her defient wash at the wharf during the tourist season.

0-eon Bowman finds that he has progressively lees time to admire the view. He suffers from the common ailment of being bogged down with paperwork and regards the present transport scene with slightly Jaundiced eye, "We still carry livestock, but It is becoming increasingly difficult to do so profitably," ha said "There is always some trade, no matter the time of year but the busiest periods occur In August and September. This is when the lambs are moved, mainly to markets in Stirling, Paisley, Dalmally and Oban. The bulk of the cattle will be carried in October and, of course, there is wool to be moved at shearing time.

"Over the years there have been countless rules and regulations formulated which, we have been told, would lead to greater efficiency all round while at the sem@ time removing from the Induetry thine aro= gue' operators who have proved to be a continual mil= Bence.

"It hasn't worked. Things just get More and more difficult for the professional operator, while the aowboys seem to grow More prosperous. Legislation is now so eornplex that very often an operator doesn't know that he is doing anything wrong until he is stopped and told about it.

"Annoying differences exist between what you are allowed to do with one vehicle and what you can do with another. I have a Ford Cargo which Is used to go to the fruit market In Glasgow and I have to send two men with it = one to drive It there and another to drive it back. It's bad enough having to use two men to do a job that could quite comfortably be done by one, but when you consider that the Bedford l use on council work for toad grit= ling in the winter can be driven, legally, by one man for as many hours as God sends then something, somewhere, is Very wrong, "Another Sore point is that I have to pay vastly More to licence my cattle trucks than a farmer doing exactly the same job. Ha pays just EEL The only vehicle I have here that I can tax for LSO is my Lend Rover.

"This means that It is rare for me to be asked to move small numbers of cattle or sheep. The farmer shifts them himself — either in a float or in a small trailer = but it is people like me who have to provide the bigger vehicles to do this work at peak times."

Having been brought up in the country, Mr Spearman realises that moving cattle necessarily involves some inconvenience. The animals get tired, they need to be watered even fad if the journey is peril= oulerly long) and he has no complaints about this.

"We once had to transport some animals from here to Aylesbury. it was too long to make it non-stop, so the trip was broken at Mother', market where the beasts were unloaded and attended to But It Is possible, given recent advenom in trucks end trailers, to cover long distances much quicker than before. On one Job we had to move ell the animals from one farm here to another at retterceirri, We Were weeks at that and yet managed every trip in eight hours, with 30 COWL sometimes 40 calves and even 400 sheep as cargo."

Kamm is less than 100 miles from Glasgow, but for the first nine miles it is tough going on single track roads with passing places. The journey can be shortened by running to Du= noon and taking a ferry across the Clyde. It saves b0 miles and = More importantly = the frust• rating run down the banks of Loch Lomond where, partial= lerly In the summer months, traffic Is reduced to a crawl be cause of swarms of tourists, many with caravans.

Even so, Geoff Spearman Is reluctant to use the ferry. It Is a half-hour trip of only four miles and yet the charge for his Scania end trailer is nudging £40 one way. It is a lot of money Just to save 60 miles and a bit of heat around the collar.

However, with the Government seemingly secure in office, the pre-election promises on Road Equivalent Tariff have been tucked away, presumably only to be trotted out again should danger threaten.

Geoff Spearman is not the kind of man to place too much reliance on outside help in any case. He gives the impression that both his pride and his pleasure are derived from the fact that — against the odds — he is still managing to make a living in a tough environment.

Around his yard lie the bones of his old workhorses: Fords, Leylands, Bedfords and the cab from an Atkinson. "The Gardner out of that went into a boat," he recalls.

All maintenance work is carried out at Karnes Wharf and with such effect that his Scania 110 tractive unit so impressed the DoT examiners last time it went for inspection that they wrote to Geoff complimenting him on its condition. The truck is now approaching its 12th birthday and has never missed a beat. "I won't tell you how much oil has gone into and come out of that engine — but it has certainly kept it running," said Geoff.

Until recently the company was run by three brothers, Geoff, Basil and George Spearma n. Basil died last year. "Now," said Geoff. "There are just the two of us. After us that will be it — the end of Spearman's Transport."

But the twinkle in his eye hints that the.end is still some way off.