Driver of the Year in Germany

Page 25

Page 26

Page 27

Page 28

Page 29

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

Wynne Phillips was voted champion CM lorry driver of 1979 and so won himself a Michelin European study award Trn Blakernore went with him

we sho:oiu take appeared on the screen. If we got too close to the vehicle in front we were warned by the word "Abstand' (distance) on the screen.

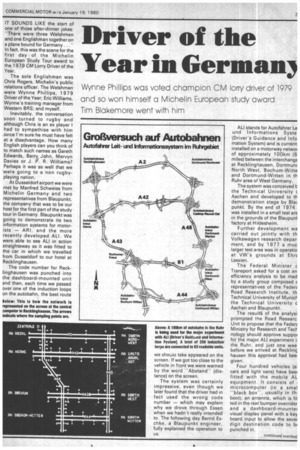

The system was certainly impressive, even though we later found that the driver had in fact used the wrong code number — which may explain why we drove through Essen when we hadn't really intended to. The following day Bernd Eschke, a Blaupunkt engineer, fully explained the operation to ALI stands for Autofahrer Le und Informations Syste (Driver's Guidance and Info mation System) and is current installed on a motorway netwoi of approximately 100km (6 miles) between the interchang€ at Recklinghausen, Dortmunc North West, Bochum-Witte and Dortmund-Witten in th Ruhr area of West Germany.

The system was conceived the Technical University Aachen and developed to th demonstration stage by Blat punkt. By the end of 1974 was installed in a small test are in the grounds of the Blaupunl factory at Hildesheim.

Further development wa carried out jointly with th Volkswagen research depar meet, and by 1977 a muc .larger test area was in operatio at VW's grounds at Ehri. Lessien.

The Federal Minister c Transport asked for a cost an efficiency analysis to be mad by a study group composed c representatives of the FedeN. Road Research Institute, th Technical University of Munich the Technical University c Aachen and Blaupunkt.

The resultS of the analysi prompted the Road Researc Unit to propose that the Feder Ministry for Research and Tech nology should approve suppor for the major ALI experiment ii the Ruhr, and just one wee before we arrived at Recklinc hausen this approval had beei given.

Four hundred vehicles (al cars and light vans) have beei fitted with the mobile AL equipment. It consists of microcomputer (in a smal 'black box'', usually in th, boot); an antenna, which is fit ted in the rear bumper overrider and a dashboard-mounte( visual display panel with a key board input to allow the sever digit destination code to tor punched in, All drivers have been asked use the system at least once a 3y, and it is hoped that the (periment will be complete by lid 1980.

The test area has 250 inducon loops buried in the itobahns. lanes, and 83 roadde units which relay informaDn via existing telephone lines the central computer at the ecklinghausen Autobahn Cene. All vehicles passing over the pop have information about lem recorded by the computer, ten those not fitted with ALI. Bernd Eschke, Blaupunkt's lgineer, was particularly proud, at a single loop in each lane as all that was needed with the /stem — usually two loops are :quired to measure vehicle Deed.

We were all surprised at how iuch could in fact be detected y the loops. Not only is each .hicle's speed measured but its istance from the vehicle in ont, the exact time at which it, assed, whether it is a car or a oods vehicle, and even the ?,hicle's height.

With this information :corded, the central computer able to calculate the optimum )Lite to any given destination, iking into account the traffic ensity on autobahns leading to ALI-equipped cars have this 'formation fed back to them 'hen they pass the loops and ie driver is advised to take the ext exit, continue straight lead, take the second exit, or tatever happens to be the best )ute. These instructions are iven 1km (0.6 miles) before ie next exit or interchange.

Mr Eschke went on to explain at the maximum capacity of a )ad is reached when as many .hicles as possible are travelno on it without safety being affected. As speed increases, the safe distance between vehicles increases proportionately faster and, of course, the denser the traffic the further speed falls.

For any stretch of motorway there is an optimum traffic intensity (the number of vehicles passing a point in a given time) and traffic density (the number of vehicles on the stretch of road at the same time). The relationship between density and intensity is shown on the road's "fundamental diagram". At maximum traffic intensity the speed achievable is quite low, being between 60 and 80km /h (37 and 50mph). ALI's aim is to get as close as possible to the. curve maximum without actually going beyond it.

After examining a roadside unit on the A2 autobahn, our champion lorry driver took an Audi 100 to the Recklinghausen Autobahn Centre, using ALI to guide him. I am pleased to report that both driver and guidance system worked well and we all arrived on schedule.

Wynne particularly liked the safety feature that prevents the destination code from being input while the car is moving. It really wouldn't be a good idea to have drivers pressing numbered buttons while travelling at the high speeds permissible for cars on the autobahns.

At the Autobahn Centre some of the capabilities of the central computer were demonstrated to us. It was possible, for example, to obtain a printout for that afternoon showing the number of cars and commercial vehicles that had passed a given point on the autobahn between Recklinghausen and Dortmund.

The data showed the number of vehicles that passed every five minutes and also gave their

average speed. Commercial vehicles are limited to a maximum speed of 80km /h (50mph) on autobahns in West Germany and it was interesting to see, therefore, that on several occasions that afternoon the average speed of trucks on that particular autobahn had exceeded 90km /h.

Individual vehicles cannot be identified by the computer, so there is no question of prosecutions resulting from the data. But it is obviously a great benefit to have accurate and up to the minute information on traffic density and how fast that traffic is moving.

Considering some drivers' opposition to the tachograph in Britain, Wynne's manager Eric Williams wondered how they would react to a system of this kind; but he agreed that haulage operators stood to benefit from it much more than private motorists.

Bernd Eschke estimated that if and when the ALI units go into production they will cost no more than a good car radio, approximately .£70. If for that price a maximum weight vehicle is able to avoid traffic jams in motorways, then it won't take long to recover the cost.

'There is some friendly rivarry' in Blaupunkt between the ALI engineers and the ARI engineers, who weren't going to allow us to leave Recklinghausen without a full description of the way ARI works.

The letters ARI stand for Autofahrer Rundfunk Information (driver's radio information system) and the system has been in operation in Germany since 1974. Austria began to operate it two years ago and it is currently being introduced into Switzerland.

There are approximately 360 VHF radio stations in West Germany, and 90 of them offer a service to the motorist giving reports on traffic conditions and suggesting alternative routes when there are delays.

To receive the relevant information a driver obviously has to be tuned in to the correct station, and this is where ARI helps. Each traffic station transmits inaudible coding tones which are decoded by ARIequipped radios which then may be tuned in (manually or automatically) to the appropriate station.

Pushing the ARI button on an ''Arimat" class radio excludes all radio stations not providing traffic news, leaving only the traffic information transmitter audible. The ARI lamp lights up to give additional indication.

The "Super Arimatclass has the additional facility of raising volume to a pre-set level during a traffic announcement, even if it has been previously reduced to zero. Cassette music is also interrupted during the announcement.

"Arimat Deluxe" receivers 'espond to an area code as well. Nest Germany, Berlin and 4ustria are divided into six areas lettered from A to F, and on long :rips between areas the code ielps in finding the designated :raffic information station that supplies information for a given

3rea.

The appropriate letters and the frequencies of the stations are shown on blue signs beside :he motorway. if contact with a selected station is interrupted, a one warns that another station should be tuned in or a new area ;ode letter should be turned to. Nhen the decoder is fitted to a self-seek radio, the automatic station finder stops only at trafic information stations.

Chris Rogers wondered if ARI suffered from the same defect as he British local radio system — hat motorists often received nformation about a jam in vhich they had been stuck for )erhaps twenty minutes ilready. We were told that this vas not so in Germany where he Minister of Transport has recommended that not more than five minutes should elapse between a traffic incident and the reporting of it over radio.

Blaupunkt believes that this can only be achieved with the use of automatic registration systems such as the ALI induction loops; and it is claimed that at present time lapses of up to 15 minutes are normal and found to be fairly satisfactory.

Traffic information is delivered to the radio stations by police, automobile clubs and rescue services, and emergency phones are set up at 2km intervals along the motorways.

When our hosts from Blaupunkt left us at our hotel in Recklinghausen on Tuesday evening, we were totally convinced that with ALI and AR1 to guide us all there was no possibility of getting lost on the way home.

On the third day in Germany we had the chance to look around Dusseldorf —liter&ly translated it means -village on the Dussel' — while Manfred Schweiss set off by car for

Munich where we were to meet him later.

Around 80 per cent of Dusseldorrs centre was destroyed during the Second World War, so many of the buildings are relatively new; but there is still an "altstadt" (old town) with many interesting h,istorical buildings. r The modern 70,000 capacity football stadium was impressive and made Wynne feel quite at home because its construction is similar to that of the national stadium at Cardiff — although of course Dusseldorf doesn't have any rugby posts.

I was surprised to learn that the town had a park especially for dogs (they are not allowed in other parks). I wondered if they had to pay to get in, and if so would it be in "Deutschbarks''?

Our train for Munich left a busy Dusseldorf station exactly on time at 12.29. We were told that it is unusual for trains to be late in Germany. The 600km (373 mile) journey was to take just over seven hours, with the diesel electric locomotive stopping at eight stations en route.

The first part of the journey was particularly dramatically scenic as the line followed the Rhine valley and we called at Cologne, Bonn, Koblenz and Wiesbaden.

Here the train changed direction and headed east for Frankfurt. By this time we had discovered that British Rail doesn't have a monopoly on poor restaurant facilities — the restaurant car was one waiter short and consequently we had to wait an hour to be served with a pretty poor lunch. However, the dinner we were to have at Munich that evening would more than compensate for it.

Manfred had booked a table for dinner at the Restaurant

Aubergine — the only three-stai Michelin restaurant in \New Germany. In the Michelin Rec Guide to Germany for 1979 twc stars is the most prestigious award, meaning that the restaurant has "excellent cooking" and is "worthy of a detour-. Three stars could only mean "out of this world",

By the end of the eghi courses we all agreed that itiwas the best meal that any of uhac ever experienced and we b ,gan to envy the Michelin inspectors.

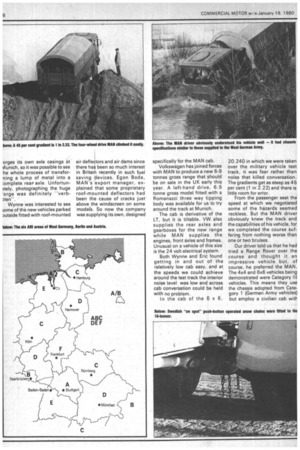

The sampling of the Aubergine's delights was not the only reason for our going to Munich, however. The following day we made our way to the MAN plant on tq outskirts of the city. MAN stands for MaschinenfabrikAugsburg-Nurnberg and the company also has plants at Penzberg, Watenstedt, Brunswick and Nuremberg. At Munich about 8500 people are employed producing, we were told, 60 to 80 vehicles per day.

There are also two test tracks at Munich — one "on road" and one very definitely "off-road" — and Wynne was able to try both of these later that day but first, together with a party of British operators, we were given a tour of the factory.

Lorries with a multitude of specifications are produced by MAN including eight wheelers, six wheelers, forward control, normal control, tippers and tractive units; and a computer is used to ensure that the right component gets to the right part of the factory at the right time.

The rear axle production line is so arranged that the components are delivered along lines at right angles to it and are transferred to the main line with the minimum of effort by the use of counterbalanced hoists. MAN orges its own axle casings at V1unich, so it was possible to see he whole process of transforning a lump of metal into a omplete rear axle. Unfortunstely, photographing the huge 'orge was definitely ''verb)ten".

Wynne was interested to see some of the new vehicles parked Dutside fitted with roof-mounted air deflectors and air dams since there ha, been so much interest' in Britain recently in such fuel saving devices. Egon Bode, MAN's 'export manager, explained that some proprietary roof-mounted deflectors had been the cause of cracks just above the windscreen on some model's. So now the company was supplying its own, designed specifically for the MAN cab.

Volkswagen has joined forces with MAN to produce a new 6-9 tonnes gross range that should be on sale in the UK early this year. A left-hand drive, 6.5 tonne gross model fitted with a Romanazzi three way tipping body was available for us to try around the track at Munich.

The cab is derivative of the LT, but it is tillable. VW also supplies the rear axles and gearboxes for the new range while MAN supplies the engines, front axles and frames. Unusual on a vehicle of this size is the 24 volt electrical system.

Both Wynne and Eric found getting in and out of the relatively low cab easy, and at the speeds we could achieve around the test track the interior noise level was low and across cab conversation could be held with no problem.

In the cab of the 6 x 6, 20.240 in which we were taken over the military vehicle test track, it was fear rather than noise that killed conversation. The gradients get as steep as 45 per cent (1 in 2.22) and there is little room for error.

From the passenger seat the speed at which wenegotiated :some of the hazards seemed reckless. But the MAN driver obviously knew the track and the capabilities of his vehicle, for we completed the course suffering from nothing worse than one or two bruises.

Our driver told us that he had tried a Range Rover over the course and thought it an impressive vehicle but, of course, he preferred the MAN. The 4x4 and 6x6 vehicles being demonstrated were Category Ill vehicles. This means they use the chassis adopted from Category 1 (German Army vehicles) but employ a civilian cab with tingle tyres, helical coil springs, ow-torsion chassis and large jround clearance.

I was relieved that the next lay's drive to Villingen was ;onsiderably more sedate. MAN tupplied us with a 19.280 fourvheeler normally used with a irawbar, but on this occasion aden to 16 tons gross without a, railer.

Wynne, Eric and I took turns )enind the wheel on the journey rom Munich to the Black Forest vith Wynne driving the final leg o Kienzle's headquarters. It vasn't easy to keep the powerul 16 tonner below the legal mit of 80km /h (50mph) on the litobahn, but the works driver warned us that if we exceeded it we were liable to on-the-spot fines.

When we came to long steep descents with lower speed limits for heavy vehicles it was noticeable that most of the German drivers were obeying them. Lane discipline was also strictly kept, with vehicles pulling back in immediately after overtaking., Used with drawbar trailers generally, the 19.280 is already a popular vehicle in West Germany and we were told it is intended to introduce it to Britain in 1981. Perhaps by that time drawbars will be more popular in this country.

The particular vehicle we had was fitted with a Hungarian driver-warning device which was intended to prevent a driver from falling asleep, and it seemed to me a reasonable idea.

When switched on, the "Reaconwould emit a high pitched tone if the driver didn't operate any control (clutch, brake, indicators etc) for three minutes. The noise was enough to prevent anybody from dropping off.

The final part of the CM Lorry Driver of the Year Study Tour was spent with Kienzle who first made a tachograph in 1928 and now claims to be the biggest manufacturer of the instrument in the world. With legislation concerning the tachograph. being laid before the British Parliament during the month of the trip, it was certainly a topical visit.

An analysis of Wynne's tachograph disc from the MAN confirmed that his driving is exemplary. Gerhard Toete, Kienzle's export manager, explained that even though motorway driving is the most difficult to assess it is still possible to judge a driver's ability from the speed trace on the disc.

Generally, the closer the maximum road speed is to the average road speed, the more economic is the driving. High speeds, sudden acceleration and heavy braking all use more fuel, and this wasteful style of driving is indicated on a disc by needle-type speed peaks. More rounded peaks show that the vehicle has been gradually accelerated and braked and thus driven more economically and safely.

Of course, a lot more information than this can be found

on a tachograph chart. This wat clearly demonstrated to us a. Kienzle's accident analysis unit, which in 1978 provided report: on over 3000 accidents.

Each chart analysis is madE with a special microscope which allows the time-depenciery recordings to be measured tc within an accuracy of onE second.

The reference line on the instrument has a thickness of only 3 microns (3/1000mm). A tenfold photographic enlargement of the segment of the chart, showing the measuring points, accompanies each report.

Because the analyses are used as evidence in court cases, accuracy is particularly important and the measuring ranges of the chart and tachograph are compared to ensure that they are identical. The accuracy of the recording trace is also checked, and an overall comparison is made between the disc and the accident report to ensure that they do refer to the same incident.

"Journey Recorders'', the tachograph's forerunner, were made compulsory for buses in Germany in 1939, and Wynne was particularly interested in Kienzle's tachograph museum with models dating back to 1928 and including some from other companies.

We all would have liked to have spent more time at the Kienzle factory, but the plane at Zurich wasn't going to wait for us. Wynne and Eric had the train journey to Wales ahead of them after we landed at Heathrow and I've an idea that they may have slept for a large part of it. Wynne's final comment at the end of his "unforgettable"' study tour — "'Dieu, I'm worn out.