An Early Leyland Motor Wagon.

Page 14

Page 15

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

Described=_by its Builder, Mr. James Sumner.

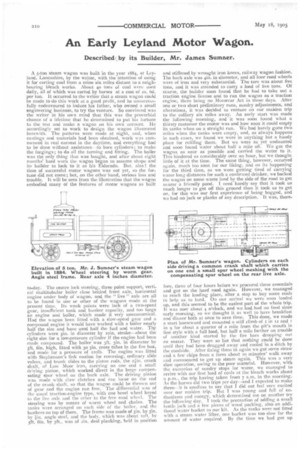

A 5-ton 'steam wagon was built in the year 1884, at Leyland, Lancashire, by the writer, with the intention of using it for carting coal from a mine six miles distant to a neighbouring bleach works. About 44) tons of coal were used daily, all of which was carted by horses at a cost of 2S. Od. per ton. It occurred to the writer that a steam wagon could be made to do this work at a good profit, and he unsuccessfully endeavoured to induce his father, who owned a small engineering business, to try the venture. So convinced was the writer in his own mind that this was the proverbial chance of a lifetime that he determined to put his fortune to the test and make a wagon on his own account. He accordingly set to work to design the wagon illustrated herewith. The patterns were made at night, and, when castings and materials had been obtained, work was commenced in real earnest in the daytime, and everything had to be done without assistance—to bore cylinders; to make the forgings; to do all the turning and fitting. The boiler was the only thing that was bought, and after about eight months' hard work the wagon began to assume shape and its builder to look to it as his Eldorado. But, alas! the time of successful motor wagons was not yet, so the fortune did not come; but, on the other hand, serious loss and trouble. It will be seen from the illustration that the wagon embodied many of the features of motor wagons as built

to-day. The centre lock steering, three point support, vertical multitubular boiler close behind front axle, horizontal engine under body of wagon, and the "live " axle are all to be found in one or other of the wagons made at the present time. Its weak points were lack of a two-speed gear, insufficient tank and bunker capacity, and too large an engine and boiler, which made it very uneconomical. Had the wagon been fitted with a slow-speed gear and a compound engine it would have worked with a boiler nearly half the size and have used half the fuel and water. Thp cylinders were sin. in diameter by min, stroke—about the right size for a low-pressure cylinder if the engine had been made compound. The boiler was 3ft. 3in, in diameter by sft, 6in. high, fitted with 3o sin. cross tubes in the fire box, and made for a pressure of 12o1b. The engine was fitted with Stephenson's link motion for reversing, ordinary slide valves, and trunk slides to the piston rods, the 24in. crank shaft, of Low Moor iron, carrying on one end a small driving pinion, which worked direct in the large compensating spur wheel on the back axle. The driving pinion was made with claw clutches and ran loose on the end of the crank shaft, so that the wagon could be thrown out of gear and the engine run free. The differential was of the usual traction-engine type, with one bevel wheel keyed to the live axle and the other to the free road wheel. The steering was by means of worm wheel and chains. The tanks were arranged on each side of the boiler, and the bunkers on top of them. The frame was made of sin. by Sin. by bin. angle steel, and the body, which was about mit by 5ft. 6in. by aft., was of zin. deal planking, held in position

and stiffened by wrought iron knees, railway wagon fashion. The back axle was 4in. in diameter, and all four road wheels were of iron and very substantial. The tare was about five tons, and it was intended to carry a load of five tons. Of ccurse, the builder soon found, that he had to take out a traction engine license and to run the wagon as a traction engine, there being no Motorcar Act in those days. Alter one or two short preliminary runs, sundry adjustments, and alterations, it was decided to venture on our maiden trip to the colliery six miles away. An early start was made the following morning, and it was soon found what a thirsty customer the motor was and how soon it could empty its tanks when on a straight run. We had barely gone two miles when the tanks were empty, and, as always happens in such cases, we found we were in anything but a handy place for refilling them. But we were as yet undaunted and soon found water about half a mile off. We got the wagon as near as possible and carried the water to it. This hindered us considerably over an hour, but we thought little of it at the time. The same thing, however, occurred again, much too soon for our liking, and on its happening for the third time, as we were getting tired of carrying water long distances for such a confirmed drinker, we backed the wagon on some waste land by the side of the road to get nearer a friendly pond. I need hardly say that it took us much longer to get off this ground than it took us to get on, for this was our first experience of being bogged, and we had no jack or planks of any description. It was, there fore, three of four hours before we procured these essentials and got on the hard road again. However, we managed to reach the loading place, after a stop to buy some coals to help us to land. On our arrival we were soon loaded up, and this seemed to be the easiest part of the whole trip. It was now about 4 o'clock, and we had had no food since early morning, so we thought it as well to have breakfast and dinner both at once to save time. This done, we made a start homeward and mounted a stiff climb of I in 12 and 1 in 9 for about a quarter of a made from the pit's mouth in fine style with a full load, but half a mile farther on trouble of another kind started by the fire bars dropping out en masse. They were so hot that nothing could be done until they had been dragged away and cooled in a ditch by the roadside. After fixing them in again we got some straw and a few chips from a farm about to minutes' walk away and commenced to get up steam again. This was a very slow operation, owing to the poor material. However, with the exception of sundry stops for water, we managed to arrive with our first load of coals at the bleach works about 9 p.m., the trip having taken from 7 a.m. in the morning. As the horses did two trips per day—and I expected to make threeit is needless to say that I did not feel very excited over our maiden trip. But I was young and full of enthusiasm and energy, which determined me on another try the following day. I took the precaution of adding a small hottle jack and a few pieces of wood packing, also an additional water bucket to our kit. As the tanks were not fitted with a steam water lifter, one bucket was too slow for the amount of water required. By the time we had got up steam, oiled round, and tightened all the nuts found loose from the previous day's running, it was nearly 9 o'clock when we started. In order to make up lost time we went at a very brisk pace, which made the buckets dance about the empty wagon with an awful clatter. My stoker thought he would stop the noise by putting one bucket inside the other and the bottle jack in the top one, so as to weight them down and keep them quiet. Imagine our surprise the first time we stopped to take water on finding that the jo:ting had caused the jack to knock the bottoms out of both buckets! Delay number two happened a little later, when we were about half-way on our journey. The water gauge glass broke, but as I expected to be able to get a new glass at the colliery I decided to go on without one. My concern was great, however, when a little later the injector (the only boiler feed) began to give trouble, evidently not being satisfied with the purity of water given to it. I do not remember what time we got to the mine on this day, nor the hour when we obtained something to eat, but I do remember that all seemed to be one long chapter of acedents and delays from beginning to end. First the injector

would not work, then a steam joint would blow out. Towards night, when about half-way home, to prevent the wagon's backing on .soft ground when getting near a pond to take water, I suddenly reversed the engine with steam on, smashing the differential wheels to such an extent as to be unable to move. I then managed to lock the broken wheels by means of a chain, which got loose several times before we arrived home. Apropos the consumption of coal and water, a local wag, who was having a ride home, took notice how often it was necessary to replenish the bunkers from the load, and remarked to a friend that it was a good thing I had not to take the load to Preston, about six miles farther on, as he was afraid I should have no coals left to deliver, and would have to begin all over again. It was quite evident that the wagon would not do in this state. In two days it had made two journeys instead of six. In addition to renewing the differential gear, many other things required alteration, and as funds were now too low to permit this, the dream of the previous two years was dispelled, and the wagon had, most reluctantly, to be put on one side until matters developed as I hope to explain again,