Sound and spray

Page 51

Page 52

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

ANYONE who drives on a motorway in a private car or light van in the rain will not need telling of the visibility problems caused by tyre spray. This is especially true of a twin rear axle arrangement with the axles set fairly close together.

Everyone describes the phenomenon as "tyre spray" )ut, strictly speaking, does the A/hole of the blame rest with the :yre?

According to the Michelin lyre Company, it does not, as I dund when I talked to Ray

Jowell, technical liaison -nanager of Michelin.

The difficulty which faces all yre manufacturers is that the >pray is the result of the water )eing removed from between he tyre and thc road — and this s what the tyre is designed to do n the first place.

Water is a lubricant to rubler, so it is essential to remove his water from between the two urfaces to give the truck some It is not generally realised just how much water the tyre is expected to expel. For example at 48km (30mph) one tyre will shift approximately 9 lit/min (2gpm) when there is a depth of water on the surface of 2mm (about 3/3210.

In heavy rain the depth of surface water can often exceed this figure. But this volume of water is for one wheel only — a trailer bogie has eight of them! So it is easy to see where the spray comes from.

Although simple in theory, the mechanics of water expulsion, are not quite so straightforward in practice.

The principle is based on the tread pattern flexing and squeezing the trapped water out at the back and at the sides.

That explains the origins of the spray, but it doesn't go anywhere to suggesting ways and means of cutting down its nuisance value to other road users.

The tyre companies argue the of the tyre doing its job effectively and removing the water from between the tread and the road. So if it is not their responsibility, where do we go from here?

Some type of mud wing is probably the answer, but opinions vary as to what shape it should take. This is a topic which has concerned the Transport and Road Research Laboratdry which has been experimenting with various types of mud wing.

It has found that the fully enveloping type with a lip coming to the top of the tyre is the most suitable. In this form, it minimises the swirling effect which makes the spray such a visibility hazard.

It has been suggested by many sources that the only answer is to go to fully enclosed wheels, but manylleet engineers would resist this move strongly as such a design would prevent the air from circulating around the tyres and brakes with a It would also make tyre inspection considerably more difficult.

With the increasing amount of work put in by the vehicle and component manufacturers to reduce the overall noise level of a heavy vehicle, the noise generated by the tyres is becoming a significant factor in the pattern.

Improved silencer design, en6ine encapsulation etc have all don.; a great deal to reduce the noise level of the heavy commercial vehicle.

However, the contribution of the tyres to the overall noise emission is rather difficult to assess owing to the use of the British Standard drive-past test.

For operators not familiar with this method, it consists of approaching the test area with the lorry at a road speed which corresponds with an engine speed defined as three-quarters of the speed at which maximum: power is developed.

Therefore, if the engine develops, say, 194kW (260bhp) at 2,400rpm then the lorry should cross the start line with 1,800rpm on the clock. The particular gear selected is the one which just prevents the governor cutting in during the 20m (65ft 8in) test run.

When the front of the vehicle reaches the starting position, abiding by the conditions I've just mentioned, the driver floors the throttle and accelerates through the test box past the microphone.

Under these conditions, the current limit for noise emission as specified in the Motor Vehicles (Construction and Use) . Regulations 1973 is 89dB(A) for a truck over 150kW (200bhp).

However, a study by the Transport and Road Research Laboratory suggested that, when measured by the drivepast test, the type of noise was unlikely to contribute significantly to the overall noise emitted by the lorry.

But the report went on to say that in the opinion of the TRRL, the tyre /road surface noise would nevertheless be the predominant source -of noise from the envisaged quieter trucks of the future, when they were travelling at speeds approaching 100km/h I62mph) on dry roads and at speeds over 50km /h (31mph) on wet roads.

If this is true, it looks as though a new British Standard noise measuring technique is called for.

As far as the noise itself is concerned, the contributing factors which have the most influence are vehicle speed, tread pattern, road surface texture and whether the surface is wet or dry.

As far as the tyre manufacturer is concerned, he has influence over one factor alone — the tread pattern. Unfortunately two requirements in the design of a tyre clash head on.

An open tread, designed to get rid of a considerable amount of water, is also likely to be a comparatively noisy tyre. To the problem of satisfying both these requirements must be added the request of every transport operator in the country — namely, that he gets good mileage out of the tyre.

Michelin is obviously anxious to cut down the tyre-emitted noise, but the company is apprehensive about the number of different road surfaces which can be found throughout the country — and road surface has just as much influence over the tyre emitted noise as the tyre itself.

Most drivers will have noticed the 'tyre noise' warning. signs on certain sections of the motorway network; for example on the M1 at Luton. This is a classic example of the situation that Michelin dreads.

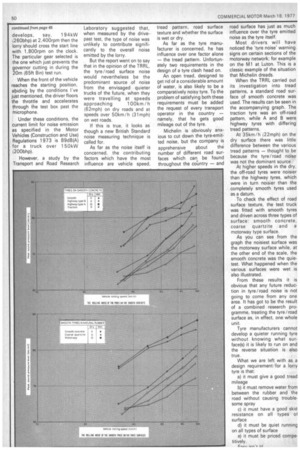

When the TRRL carried out its investigation into tread patterns, a standard road surface of smooth concrete was used. The results can be seen in the accompanying graph. The traction tyre was an off-road pattern, while A and B were highway tyres with differing tread patterns.

At 35km / h (22mph) on the dry surface there was little. difference between the various tread patterns — thought to be because the tyre/road noisewas not the dominant source.

At higher speeds in the dry, the off-road tyres were noisier than the highway tyres, which were in turn noisier than the completely smooth tyres used as a datum.

To check the effect of road surface texture, the test truck was fitted with smooth tyres and driven across three types of surface: smooth concrete, coarse quartzite and a motorway type surface.

As you can see from the graph the noisiest surface was the motorway surface while, at the other end of the scale, the smooth concrete was the quietest. What happened when the various surfaces were wet is also illustrated.

From these results it is obvious that any future reduction in tyre /road noise is not going to come from any one area. It has got to be the result of a combined research programme, treating the tyre/road surface as, in effect, one whole unit.

Tyre manufacturers cannot develop a quieter running tyre without knowing what surface(s) it is likely to run on and the reverse situation is also true.

What we are left with as a design requirement .for a lorry tyre is that: a) it must give a good tread mileage b) it must remove water from between the rubber and the road without causing troublesome spray c) it must have a good skid resistance on all types of surface d) it must be quiet running on all types of surface e) it must be priced competitively.