FROM THE RIVER TAFF TO THE KARIBA DAM

Page 66

Page 67

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

IT'S A LONG WAY from He Kariba Dam in Zambia, but n employees of Robert Wynn a Newport.

When Wynn won a contract to transport giant electrical transformers from Dar Es Salaam to Kariba it invited its employees to volunteer for African service. "The response was immediate and overwhelming", said Mr Noel Wynn, the managing director, told me. "It seemed that everyone wanted to be involved in the Kariba project even after we had spelled out the difficulties, dangers and discomfort."

Back in March 1974 United Transport Overseas, Wynn's parent company, had received an inquiry from civil engineering contractors Merz and McLellan on the feasibility of hauling transformers overland from Dar Es Salaam in East Africa to the Kariba Dam north bank. This is the physical link between Zambia and Rhodesia.

At first the mind boggled," said the assistant general manager, Mr John Wynn. "We pictured all kinds of problems. But we've never refused a challenge yet and this was treated as one more inquiry."

The first step was a series of briefing meetings with UTO and Merz and McLellan. The physical difficulties were exam wport, Monmouthshire, to the ot too long it seems for the nd Son Ltd of Albany Street, Med on paper, personnel problems were studied and a rough costing was compiled.

Every heavy movement undertaken by Wynn is studied on the site and this was the next move. John Wynn and his operations manager, Mr Rex Evans, took off from London's Heathrow Airport on March 26 for Lusaka—five days after UTO had received the initial inquiry.

The first step was the Kariba site. "There's no point in looking at the loading point and the route if you can't discharge at journey's end," said John. And journey's end in this case proved to be down a tunnel a

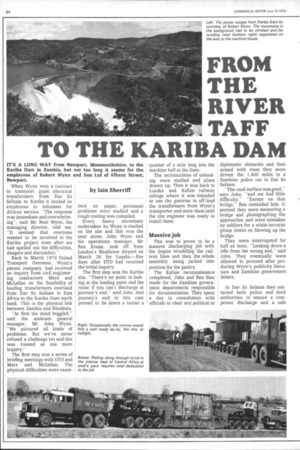

Right: Occasionally the convoy would find a well made lay-by, like this, at twilight.

Below: Rolling along through scrub in the intense heat of Central Africa at snail's pace requires total dedication to the job.

quarter of a mile long into the machine hall at the Dam.

The technicalities of unloading were studied and plans drawn up. Then it was back to Lusaka and Kafuie railway sidings where it was intended to use the gantries to off-load the transformers from Wynn's transporter and store them until the site engineer was ready to install them.

Massive job

This was to prove to be a massive discharging job with the bogies straddling the railway lines and then the whole assembly being jacked into position for the gantry.

The Kafuie reconnaissance completed, John and Rex then made for the Zambian government departments responsible for documentation. They spent a day in consultation with officials to clear any political or diplomatic obstacles and then armed with visas they were driven the 1,400 miles in a Zambian police car to Dar Es Salaam.

"The road surface was good," says John, "and we had little difficulty." "Except on that bridge," Rex reminded him. It seemed they were measuring a bridge and photographing the approaches and were mistaken by soldiers for a white terrorist group intent on blowing up the bridge.

They were interrogated for half an hour, "Looking down a rifle from the wrong end," said John. They eventually were allowed to proceed after producing Wynn's publicity literature and Zambian government letters.

In Dar Es Salaam they contacted both police and dock authorities to ensure a competent discharge and a safe escort if they won the contract. The entire route had been cine-filmed to give the crews some idea of what they were tackling and to help ensure that all necessary gear was included in the tool kits. "You can't nip back to the yard from Central Africa to pick up tensioners," said John.

The reconnaissance completed, John and Rex returned to the UK, and compiled a quote which was submitted to the civil engineers after vetting by UTO. The quote was accepted by May 21—only two months after the first inquiry.

In the estimate Wynn stipulated that the company reserved the right to subcontract a portion of the contract to another mutually acceptable heavy haulage operator. In the event the contract was granted and part of it was passed to Mammoet Transport BV of Amsterdam.

Appropriately, Mammoet means the Big Elephant.

The entire convoy was shipped out from the UK and Holland to Dar Es Salaam in mid September ready to start work on October 1 as was stipulated in the contract. The convoy comprised: Four Scammell Super Contactors; four Mack tractors, five multiwheeled, fiat-top bogies with eight-line wheels; one double swan-necked 32-wheel trailer; six caravanettes; two caravans; one Mercedes breakdown truck; one FTF tractor; one fuel and water bowser; one Peugeot estate car.

Walking pace

Although the convoy was assembled ready to load on October 1, the vessel was delayed until October 9. Three days later the long, hot, dusty, slow journey to Kariba began.

When Wynn moves heavy indivisible loads in the UK crowds gather if only attracted by the remote possibility of an accident. In Tanzania the citizens are no less curious.

Exit from Dar Es Salaam was achieved at less than walkingpace speed but with perfect police control. Once clear of the town speed stepped up to 1015 mph and was maintained throughout the 100-day trip.

On the evening of the first day out the convoy had covered a mere 70 miles and before bedding down much had to be done. The men had to cook their food, check their vehicles and assemble the safety gear. The Zambian road safety arrangements proved mosi successful—there was neither an accident nor a near miss during the entire trip. Indeed, according to John Wynn there was only one sticky patch on the 1,400-mile route. At Moroago 200 miles from Dar Es Salaam the road was badly rutted and pot-holed for 200 yards. The low-set bogies carrying up to 68 tons had to be nursed around this hazard. "It took time but it was achieved without incident," said John.

The boredom of the slow, incident-free trip was spiced with the sight of African wild life in the Mikumi Game Reserve. "At lOmph you've got plenty of time to look," according to Rex Evans.

There are always dangers of friction when hi or multi national groups find themselves working in a strange and uncomfortable environment. This could have happened on the Kariba convoy but apparently did not. "There was always a bit of good-natured leg-pulling between crews," John told me. "But in the end we won."

It seems that the Mammoet crews with their Mack tractor units offered mock sympathy to the Welshmen with their "oldfashioned Sc ammells" .

"Then came the escarpment towards Iringa," said Rex. It was agreed that the Macks should make the first assault with the lightest load of 26 tons..

One tractor unit started the pull round the hair-pins up the 1:10 but began to overheat and a second unit had to go to its assistance.

The next load was a 68-ton piece and because of their high gearing all three Macks were hooked up and over they went —painfully, slowly.

The Wynn section of the convoy was loudly cheered by all when a similar 68-ton load took the escarpment comfortably with only two' Scammell Contractors in attendance.

It took three hours to clear the escarpment and during this time the police had closed the road.

'Merely routine'

According to John Wynn the trip was incident free and the subsequent six movements were "merely routine". In Tanzania and Zambia only two police crews were used throughout. They were made up of a lieutenant, a sergeant and four constables.

"The exercise was carried with military precision," said John, "and it had to be because we were bound by contract to deliver on time."

So successful was the operation that Wynn was retained beyond the contract period— which should have ended in mid 1975—until last month. The company was engaged in moving other pieces from the railhead, they were too big and heavy to travel throughout by road.

Wynn's men in Africa were anxious to get home at the end of each three-month tour.

The delays meant that someone had to spend another Christmas in temperatures far removed from the sleigh bells and holly atmosphere of Wales. John Wynn told me: "We got the volunteers, however, and now if you ever hear the natives of Kafuie in Zambia singing Silent Night with a Welsh accent you'll know why."