PERPETUAL PERKING

Page 46

Page 47

Page 48

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

IT is not all that long ago since mileages of a quarter of . a million without lifting the cylinder head were looked

upon as quite remarkable for British automotive diesel engines, and in those days only comparatively large power units could be considered for this type of longevity. Nowadays, 250,000 miles has become virtually an expected mileage for an engine of over about 8-litres capacity, but it is not generally realized by how much the trouble-free life of smaller diesels built in high quantities has been increased at the same time. Some operators are still inclined to feel , that if they have diesels of under 6-litres capacity in their fleets, these are going to need expensive reworks before mileages of 150,000 have been covered.

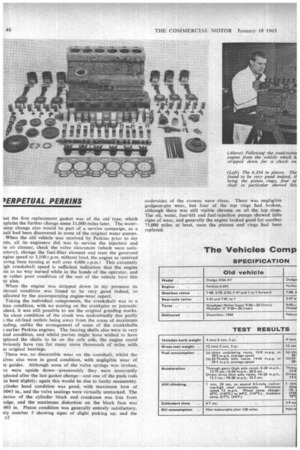

To give an answer to this, F. Perkins Ltd., Peterborough, recently made it possible for me to carry out comparative tests on two 12-ton-gross goods chassis, one of which had an engine which had covered 36,000 miles in just over nine months whilst the other had knocked up well over 180,000 miles in 23 months, both the engines being Perkins 6.354 units.

Performance figures taken , with these two vehicles show that the substantial mileage covered by the engine which had been delivered in 1960 had not resulted in its performance being drastically worse than that of the younger one; indeed, so far as acceleration and hill-climbing were concerned, the older unit tended to outstrip the new job. Fuel-consumption figures taken revealed that over a fairly easy route the old engine was barely 7 per cent heavier on fuel, whilst taken over a longer, hilly course the difference fell to a mere 4.25 per cent.

Following the road-performance tests, the old engine was bench tested, and its output found tb be 3 per cent above the makers' maximum production tolerance, and after this the unit was completely stripped down and measured for wear, whereupon it was discovered that, despite its hard life, the engine was internally very sound and could have been brought back to peak condition virtually by changing nothing more than the piston rings.

There is no doubt that this exercise with the two engines confirms that tremendous strides have been made in the life of comparatively small, high-speed diesels over the course of the past 10 years, and that for a relatively small outlay, modern engines of this type can be kept running for periods within easy reach of those normally associated with heavier and more expensive units. In fact, the lighter engine would probably cost less to run from an overall viewpoint, as those spares which do become necessary would in any case be less expensive than those needed for a larger engine. The time has almost come when the modern mass-production goods chassis has an engine which will outlive the rest of the chassis, a far cry from the days when a chassis might have two or three engines before it was considered advisable to scrap the vehicle entirely. This could even lead to operators buying more expensive vehicles with a longer potential chassis life in order to keep up with the increased power-unit life of current medium-sized engines.

Dodge 7-tonners Compared

The vehicles used for the comparative road tests were both Dodge 3166 AT 7-ton models with almost identical mechanical specifications, the only difference—and this not being of any particular significance—lying in the ratios of the two-speed axles, the older chassis having slightly higher gearing. Another Dodge, again of identical mechanical specification, had been borrowed originally for the comparison with the old vehicle, but -this had covered less than 800 miles and tests taken with it showed that it was too new and stiff to permit fair comparisons to he made. Furthermore, it had had a large refrigerated body on it, the higher wind resistance of which tended further to place the vehicle's performance well below that of the two-year-old chassis.

The tests with the new vehicle, therefore, were carried out some two weeks after those made with the older one, but test cbnditions were almost identical in each case, so the recorded figures are strictly comparable. Both chassis had platform bodywork, which had been loaded with concrete blocks to bring the gross weights to within 0-75 cwt. of each other.

Large test tanks were used for fuel-consumption measurement, and two tests were carried out on each vehicle. One of the tests entailed driving at a speed not exceeding 33 m.p.h. over an undulating 8'7-mile course, half of which was dual carriageway. Under these fairly even conditions a difference of 1.2 m.p.g. was shown. The second test • was of a more extended nature, the route consisting of 63.75 miles of poor-quality main road with several very hilly sections. Under these conditions the old vehicle was only 0-65 m.p.g. heavier on fuel than its younger fellow, which can be taken to indicate that the higher-thanstandard engine output offered fuel economy advantages on hilly stretches. Both vehicles siere driven by the same driver for each of the four tests, and this driver was well acquainted with the hilly route and so was able to make the most of each vehicle's performance, though, as on the short run, the road speed was not allowed to exceed 33 m.p.h. except when running downhill.

Although neither Dodge had wildly inaccurate sneedometers, a fifth-wheel recorder was employed for the acceleration tests. The figures obtained showed that between a standstill and 30 m.p.h. the old vehicle was more lively than the newer machine, yet for some inexplicable reason the direct-drive acceleration between 10 and 30 m.p.h. was 1 second better with the new vehicle. All in all, it can be said that there was very, little to choose between the acceleration performances: certainly the old lorry's liveliness had not deteriorated to any marked degree.

To get art indication of comparative gradient abilities the vehicles were driven . up a main-road hill of unmeasured gradient (probably no steeper than 1 in 20). A distance of approximately 0.5 mile was used for the tests, which were made by approaching the bottom of the hill at 30 m.p.h. in top gear, high axle ratio, and holding this ratio for as long as possible. the complete ascent being timed.

The old machine managed to scale the incline without the need for a gear change in 1 minute 20 seconds, but the newer chassis was not able to do this, a change from high to low axle ratio being necessary near the top of the hill when the speed had ,fallen to 10 m.p.h. The climb with the new vehicle took 18 seconds longer than with the other Dodge, whilst at no time did the speed of the old chassis drop below 13 m.p.h. No exhaust smoking was observed in either case, and the temperature rises are recorded in the accompanying data panel, from which it will be seen that the newer of the two engines was dissipating more heat to the coolant than was the older unit.

At the end of each test, during which each vehicle had covered approximately 150 miles, level checks were made to ascertain whether either unit had used any engine lubricant, but in neither case was any oil loss detectable.

On the morning of each test, cold-start times were taken, each vehicle having been left outside overnight and the ambient temperatures at the time of the starts being in the region of 3'C (37°F). Under these conditions the old engine was started in 6.7 seconds, whilst the newer unit was started in 3.9 seconds. The Perkins 6.354 is not fitted with cold-start equipment as standard; so both these starts were made in the normal way.

Following the tests with the old vehicle, its engine was removed and replaced by a rebuilt unit, after which the vehicle was returned to its owner. Before the strip-down the unit was put on the test bed and its performance compared with the ligures taken before it left the Perkins factory in 1960. The bench test showed that the engine's output had grown by some 3 per cent compared with the maximum production tolerance and the unit was actually developing 5 b,h.p. more than when it was originally passed out. Some of this can he put down to a tendency of the DPA injection pump to give a slightly increased fuel delivery over a prolonged period of running.

It is of interest to note that during its life this engine had been untouched apart from cylinder-head gasket changes at 37,583 and 48,792 miles and the fitting of a new water pump some time later. Perkins introduced a new type of cylinderhead gasket during the second half of 1961, and it is probable at the first replacement gasket was of the old type, which xplains the further change some 11,000 miles later. The waterump change also would be part of a service campaign, as a suit had been discovered in some of the original water pumps. When the old vehicle was received by Perkins prior to my :.sts, all its •engineers did was to service the injectors and se air cleaner, check the valve clearances (which were satisactory), change the fuel-filter element and reset the governed ngine speed to 3,100 r.p.m. without load, the engine as received aving been turning at well over 4,000 r.p.m.! This extremely igh crankshaft speed is sufficient indication that the engine as in no way nursed while in the hands of the operator, and IC rather poor condition of the rest of the vehicle bore this ut also.

When the engine was stripped down in my presence its iternal condition was found to be very ,good indeed, as idicated by the accompanying engine-wear report.

Taking the individual components, the crankshaft was in a lean condition, with no scoring on the crankpins or journals: ideed, it was still possible to see the original grinding marks, he clean condition of the crank was undoubtedly due partly ) the oil-feed outlets being away from the areas of maximum )ading, unlike the arrangement of some of the crankshafts earlier Perkins engines. The bearing shells also were in very ood condition, and whilst purists might have wished to have !placed the shells to be on the safe side, the engine could bviously have run for many more thousands of miles with se original bearings.

There was no discernible wear on the camshaft, whilst the alves also were in good condition, with negligible wear of le guides. Although none of the valve springs was broken. ye were upside down—presumably they were incorrectly :placed after the last gasket change—and one of the push rods as bent slightly; again this would be due to faulty reassembly. ylinder head condition was good, with maximum bow of 0045 in., and the valve seatings were virtually unmarked. The itenor of the cylinder block and crankcase was free from udge, and the maximum distortion on the block face was 003 in. Piston condition was generally entirely satisfactory, nly number 5 showing signs of slight picking up, and the c2 undersides of the crowns were clean. There was negligible gudgeon-pin wear, but four of the top rings had broken, although there was still visible chrome on all the top rings. The oil, water, fuel-lift and fuel-injection pumps showed little signs of wear, and generally the engine looked good for another 75,000 miles at least, once the pistons and rings had been replaced.