THE HALL OF FAME 2

Page 54

Page 55

Page 56

Page 57

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

This month's themed selection of nominations includes two (very different) Fords and two British brands that begin with an S.

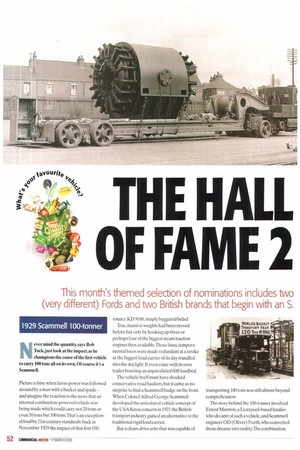

1929 Scammell 100-tonner

Never mind the quantity, says Bob Tuck, just look at the impact, as he champions the cause of the first vehicle to carry 100 tons all on its own. Of course it's a Scammell.

Picture a time when horse power was followed around by a man with a bucket and spade — and imagine the reaction to the news that an internal combustion-powered vehicle was being made which could carry not 20 tons or even 50 tons but 100 tons. That's an exceptional load by 21st-century standards: back in November 1929 the impact of that first 100 tonner, KD 9168, simply beggared belief.

True, massive weights had been moved before but only by hooking up three or perhaps four of the biggest steam traction engines then available.These fussy, temperamental locos were made redundant at a stroke as the biggest load carrier of its day trundled into the daylight. It even came with its own trailer boasting an unparalleled 60ft loadbed.

The vehicle itself must have shocked conservative road hauliers, but it came as no surprise to find a Scammell badge on the front. When Colonel Alfred George Scanunell developed the articulated vehicle concept of the USA Knox concern in 1921 the British transport industry gained an alternative to the traditional rigid load carrier.

But a chain-drive artic that was capable of transporting 100 tons was still almost beyond comprehension.

The story behind the 100-tonner involved Ernest Marston, a Liverpool-based haulier who dreamt of such a vehicle, and Scammell engineer OD (Oliver) North, who converted those dreams into reality.The combination made Marston Road Services the biggest name in UK heavy haulage;it also made the name of Scammell synonymous with heavy haulage throughout the world for almost the entire 20th century.

And it gave enjoyment to a huge number of spectators who came to gaze in awe.

It was agreed with Ernest Marston (who paid £20,000 for his new vehicle) that Scammell would give Marstons two years of operational use before another 100-tormer was allowed on the road.Tnie to their word, the second example (BLH 21) was only used to haul a portable Garrett furnace on-site until Pickfords bought it in 1934.

Ernest Marston died aged just 43 in 1934 so he didn't see the long-term impact of his dream. which stayed in service until November 1957. It was modified early in its career with a sixcylinder Gardner 6LW diesel engine,primaril■,, because the fuel consumption of the original Scammell petrol engine was less than lmpg. With nationalisation in the late 1940s both 100-tonners ended up with the Pickfords Division of British Road Services.They both survived the passage of time and have gone into preservation.

Yes, Scammell only built two of these 100ton specials. but never before, or since, has the media accurately described a vehicle launch as "taking the commercial vehicle world by storm".The Scamme11100-tonner is simply THE hero of the past 100 years Born in 1945 in Consett, Bob is a life-long road transport enthusiast. After serving 25 years in the police he left to concentrate on writing. With 18 books to his credit, this prolific writerstill enjoys his so-called job which takes him all over the world

Ford Model T

III livver. Tin Lizzie. Call it what you will, *Allan VVirm is certain that the Model T Ford was the most significant commercial vehicle ever built.

The ModelT might have been an acquired taste; it might have been technically obsolete for most of its production life. But no other vehicle introduced so many people to motoring in general and motor transport in particular— it must have put more horses out of business than any other vehicle.And no other commercial vehicle filled so many roles in peace and war over so many years.

Like the equally ubiquitous Douglas C-47/ DC3 airliner a generation later, the ModelT was significant not just through the sheer weight of numbers, but also for its unique adaptability.

It wasn't that it was necessarily the best available option in each of the hundreds of roles (few of which could have been envisaged by its creator in 1909) it was asked to fill. But the purpose-built bus/dray/ambulance/ horsebox/charaband pantechnicon/farm pickup, or whatever could do it significantly better than a Flivver, was also significantly more expensive.

Part of that adaptability lay in its construction. It might have been cheap to buy, but Ford used exotic materials like chrome-vanadium steel for the frame to ensure its strength no matter what the over-optimistic owner put on its back.

Add to that the facts that every country blacksmith knew how to fix a Ford, it was largely unbreakable and staggeringly reliable for something introduced only 20 years after Benz made the first successful petrol-engined car. No wonder it was bought in its millions.

And it wasn't only the cars that sold. In less than 20 years Ford's US plant alone built nearly 1.5 million trucks, 450,000 chassis, over 26,000 ambulances and 2,000 "deliveries"— in total nigh on two million comrnercials,not including some exports and Canadian production.

Even the UK's daft RAC Horsepower Tax system, which penalised large-bore, slowrevving engines like the Model T's 2,896cc sidevalve four, failed to prevent more than 300.000 British-built examples from finding owners.

To modern eyes the ergonomics are catastrophic, but to a public which had no legacy of standardised control layouts to draw on, the Ford's weird layout of hand throttle and three pedals (clutch, reverse and brake) were simply the way a Ford was. The clutch, incidentally, you had to hold down with a broom handle or shovel to keep first gear engaged when your left leg got tired on a long incline.

The basic car chassis bore the limitations of its eccentric two-speed epicyclic gearbox ("two speeds — too low and too high" said the wags) but on the worm-drive "Tonner" commercial chassis you could fit the Ruckstell two-speed axle or exotic add-ons like the Warford three-speed auxiliary box to give six forward speeds.

That eccentric transmission ensured that countless early owners (apocryphally at least) pinned themselves to their barn walls while hand-cranking their 'T's — the electric starter didn't turn up on the ModelT unti11920.Not that the customer necessarily wanted such effete luxury: as late as 1925 almost 187,000 customers opted forT trucks without starters; only 119,000 paid up for an electric starter.

That was the peak year of production, at over 306,000 trucks alone.The next year, production was down to 213,000 trucks, and by 1927 it was all over.

Ford shut its plants down and re-opened the following year with the totally conventional Model A. In its own terms, this was also a great success as a commercial, but never again would a Ford, or any other commercial, have the impact of the ModelT.

New Zealander AllanWinn was editor ofCM from 1985 to 1988. Trained as an aeronautical engineer, a journalism scholarship brought him to the UK in 1974. Eventually his aeronautical past propelled him to editor, then publisher ofFlight International. Now director of Brooklands Museum in Surrey, he has been competing in vintage events with a 3litre Bentley for 20 years.

Ford Transcontinental

Why has Brian Weatherley nominated the big Ford? "Pure nostalgia. Like Howard Hughes' Spruce Goose flying boat it was a marvellous Great White Hope that never quite made it."

The cruel quip about the Transconti "Overweight. over-height-and over here!" was an amusing variation on the old gag about American GIs. but it didn't do it justice.This was, after all, a truck that for its day set an incredibly high standard in long-haul tractors, despite being little more than a kit of parts.

Its cab came from Berliet, the engine from Cummins, the gearbox from Fuller and the rear axle from Rockwell. Even the hightensile steel chassis rails were shipped in from AO Stone in the States. Some said Ford made only 24 parts itself — and that included the four letters F. 0, R and Don the front. At the launch one journalist asked what Ford actually made, and was tersely told "the profit".

Teasing aside, few of the truck journalists who first drove it in 1975 were left unimpressed. Commercial Motor's technical editor, the late, and much missed Graham Montgomeri e, declared: "Drivers will love the Transcontinental...I think the Ford must be the contender for the quietest truck I've ever driven. Visibility from the cab is first class — it's the only time I've ever overtaken an F88 Volvo and looked down on it!"

Unfortunately his analysis of its suitability for the UK's miserly 32-ton gross weight limit was equally emphatic: "At 38-tonnes on the European routes its higher kerbweight would be a negligible factor — but at our tiny gross weight limit it becomes significant "An HA4234 Transconti weighed 1,200kg more than, for example, an Atkinson Borderer.

The trouble with the Transconti was that it was based on a gamble that weight limits would go up in the UK.At one time there were even whispers that the unheard of figure of 44-tonnes would be accepted by the British government of the day.

Of course it didn't happen in time. Ford tried to leapfrog the established competition in one go—and failed.

The UK wouldn't see 38-tonners until 1983 and stalled for 10 years before adding a couple of tonnes more. Ironically, when CM conducted a 40-tonne group test around our old Scottish test route back in 1980 (having acquired special authorisation to run at the higher limits) the E290"Hummin' Cummins"-powered Transcontinental gave a good account of itself.

Despite that failed gamble the Transconti wasn't a total flop. Ford sold no less than 8,735 examples, including many to big fleet operators including Midlands BRS and Birds Eye Unispeed as well as to some of my local owner-operators like KenTrowell and Lou Thurgood. I once asked Ken why he kept buying Transcontinentals and he left me in no doubt:"They're the best truck on the road!"

But the ones that really fired my imagination were the immaculate units run by Ford out of its Basildon, Essex tractor plant, You'd spot them a mile off heading through the Dartford tunnel hauling a batch of new Ford tractors to the Continent and the Middle East.

Happy days."Overweight, over-height and over here"? Perhaps. But overlooked? Never!

Editor-in-Chief Brian Weatherley joined CM in September 1978 as the 'junior' photographer, working with various CM technical greats including Graham Montgomerie, Steve Gray, Bill Brock and Tim Blake more. Despite his best efforts, he became CM's editor in 1989 before handing over the reins to Andy Salter in 2003 "with a tremendous sigh of relief!"

Sentinel S4

John Parry throws his weight behind a contender whose specs sound remarkably 21st century for a vehicle that ran on nutty slack...

What are the features that attract truck operators today? High-tech engine management systems giving good performance and economy? Definitely. Low emissions are good for the image, of course, and easy driving with no gear changing helps attract and keep drivers.

Many of these features are taken for granted today, but you might be surprised to know that they were available in the 1930s.

I hear the collective cry"you're joking". Trucks in the '30s were slow, noisy and dirty; increasingly powered by diesel engines in an early stage of development. But this nomination for the greatest truck of the past 100 years didn't burn diesel, or even petrol.

The Sentinel S4 arguably represents the pinnacle of road vehicle steam power. Some of its statistics make interesting reading. Its horizontal four cylinder in-line engine has a bore and stroke of 5.5x6in, giving a swept volume of 9.3.4 litres. Its rating of 124hp at 1,000rpm equates to a torque output of around 880Nm. Fully laden to 13 tons, this gave acceleration from standstill to 36mph in 50 seconds with a top speed of around 60mph.

A coal-fired vertical-tube boiler at the rear of the cab produces steam at 17.6 bar, superheated to 425°C. According to former CM writer Ron Cater in the 1968 Christmas roadtest, the ability to spit accurately was a useful skill, given the number of hot components around the cab.

The best Welsh steam coal is said to produce excellent combustion with no visible smoke or CO ernissions.Automatic stoking and water feed gives effective one-man operation. In a rough conversion to modern pricing, its 38 MACS per hundredweight gives running costs equivalent to a diesel doing just under 20mpg — a decent figure for a modern 7.5-tormer. The engine drives the rear axle directly through a propeller shaft so there's no gear changing in normal use, although a straightcut gear set at the rear of the crankshaft does give a low ratio for arduous conditions.

Variable valve timing is seen as a modern innovation but it featured on Sentinels since the company began production in the same year as CM's birth. A three-stage sliding camshaft controls the steam flow.The first position gives maximum power for starting off while the third is for cruising economy, with an intermediate compromise position. The same system provides reverse by the simple expedient of reversing the engine's rotation. Stopping is handled by a pair of steam operated drum brakes on the rear axle.

Downsides? Well. the 68 minutes to build up steam and the range of 190 miles to a bunker of coal would limit the S4's operational usefulness, and the 6,236kg unladen weight is greater than its 5,715kg payload. This is not the engine's fault, however, as the complete power unit including transfer box, dynamo, lubricator pump and tyre pump weighs just 408kg.

Commercial Motor's 1933 roadtest of the S4 summed it up by saying: "The acceleration and braking are good, there is remarkable power, and the suspension, tyre equipment, steering, etc are pleasing, while the manoeuvrability is quite out of the ordinary". For its technology which was so far ahead of its time, I nominate the Sentinel 54.

John Pam is Engineering Director, Europe, for Exel.