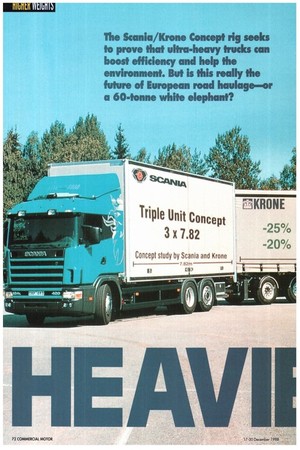

The kania/Krone Concept rig seeks to prove that ultra-heavy trucks

Page 74

Page 75

Page 76

Page 77

Page 78

Page 79

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

can boost efficiency and help the environment. But is this really the future of European road haulage—or a 60-tonne white elephant?

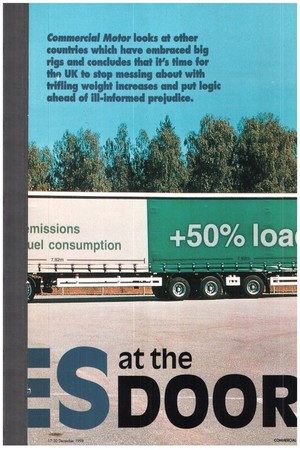

Commercial Motor looks at other

countries which have embraced big rigs and concludes that it's time for the UK to stop messing about with trifling weight increases and put logic ahead of ill-informed prejudice.

The more you carry on the back of a single truck, the more productive it becomes, and the fewer vehicles you need to carry the goods. Less congestion means greater efficiency—and there's even an environmental benefit, of which more later. You simply cannot argue with the logic behind heavier trucks.

But that's exactly what the Great British Public (and not-so-great British politicians) have attempted to do over the past 20 years. And look where it's got us. Seventeen years ago the late Sir Arthur Armitage recommended the adoption of 44-tonne trucks in his thought provoking Report of the Inquiry into Lorries, People and the Environment. And what happened? We got 38-tormers..

Then, in 1996, the Department of Transport joined the fray with Lorry Weights—A Consultation Document, which once again set out the definitive case for heavier trucks. So what happened this time? We got 40 and 41tonners. And a fat lot of good they are without any clue on future VED rates.

Which begs the question, who's to blame? The trade associations can grumble about politicians pandering to scaremongering environmentalists, but the truth is that the UK road transport industry has consistently failed to put across its case on the advantages of running heavier trucks.

Meanwhile, the argument is as unassailable now as it has ever been. So instead of faffing around with two tonnes here, or four tonnes there, isn't it time we talked about some real increases in UK truck weight limits?

60-tonne truck: The concept

In September Commercial Motor reported from the Hanover truck show on a concept project that is likely to give the environmental lobby nightmares. The Scania/Krone rig weighs 60 tonnes and is 28m long—but it does the work of nearly two conventional artics.

You'd think that of all the countries in Europe the Swedes would be green to the gills, and so they are— but that doesn't stop them running trucks at up to 60 tonnes, often on roads that are either little more than a gravel tracks or covered in snow; 24m drawbar rigs have been allowed there for years. And all the time the UK is worrying about 44 tonnes and 18.75m.

While the man on the Clapham omnibus might recoil at the mere thought of a 60tonne truck, the Swedish truck manufacturer is embracing the idea.

60-tonne truck: The green benefit

Bigger trucks need more fuel, but Scania's line is that bigger loads mean fewer journeys—something of which the environmental lobby would surely approve.

Scania's Per-Erik Nordstrom says: "The object is to demonstrate how road haulage can be made more efficient, using fewer trucks to transport the same load, and with lower impact on the environment. With more efficient trucks, each carrying 50% more load, the anticipated growth rate of heavy trucks on the roads can be considerably reduced."

The continuing cost-effectiveness of road transport will increase demand for more trucks, with forecasts of a 50% increase in transport within the EU by 2010. But rigs such as the Scania/Krone outfit could offset the impact of that increase.

"Scania and Krone have developed this concept vehicle to promote discussion and creative thinking," says Nordstrom, who has no doubts of its potential environmental benefits: "Naturally it costs more fuel to move higher weights," he accepts. "But as long as other factors, for example air resistance, are equal, the increase in fuel consumption is by no means proportional to the weight increase. And less fuel-per-tonne-transported translates directly into lower emissions, giving an environmental

Heavy trucks and NOx emissions: The heavy benefit

benefit on top of having fewer trucks on congested roads.

"Assuming a gross weight of 60 tonnes instead of 40, and using a I2-litre 420hp engine for the comparisons, the energy consumption-per-tonne drops by 20% and exhaust emissions drop by 2%," Nordstrom reports.

Just supposing that a 28m, 60-tonne rig was allowed on Britain's roads, there would be a clear eco-bonus in terms of reduced nitrogen oxide emissions. The chart above tells all.

60-tonne truck: The equipment

At the front of the Scania/Krone rig is a 420hp R124 LB6x2 standard three-axle rigid (although you could easily have a V8engined R144) with a steering rear tag-axle and a load platform designed to carry a single 7.82m container, Behind it is a two-axle converter dolly which has a steering front axle controlled by lateral forces from the coupling arm. Mounted on the dolly is a conventional fifth wheel and on top of that sits the Krone trailer.

The frame and load platform of the threeaxle semi have been extended to carry two 7.82m boxes while the trailer's rearmost axle is also steered.

One result of having no fewer than four steering axles is that the Scania/Krone concept truck can corner as well as a conventional 16.5m artic (see diagram, below left).

On a typical long-distance run the fulllength 28m rig would be used. But to placate environmentalists, the outfit can be split closer to its destination, allowing the rigid truck to continue on its own, while the trailer could be hauled by a conventional tractor.

60-tonne truck: Behind the wheel

Although not legal on the road, in September CM had a chance to drive the Scania/Krone outfit on a closed test track at the

Hanover showground. The effect opening, if a little nerve-racking. TI in-line six had no trouble getting truck going as we headed towarl left-hand bend. To complicate in 12m single-deck bus had been IN the tight side of the bend.

The Scania test driver told us to the truck in the middle of the road.

of the long trailer behind we started out extra-wide to allow for the cu OK, you don't have to do that, just I the middle," he reassured us. We wholly convinced as the gap bets trailer and bus appeared to narrow.] as the trailer started to track tF mover, it got no smaller.

Meanwhile, a glance in the offsie (our truck was a left-hooker) showed ing edge of the trailer kicking out ak We could imagine an inexperience taking out sets of traffic lights and n without even trying, Indeed, the turning action of the most peculiar because, at first, nothii to happen while it begins to follow i into the corner; then, as the steer ax dolly starts to work, out pops the fror most disconcerting.

Yet, after a couple of laps, we we ning to get the hang of it and, by re ing to drive it as a drawbar rather artic, we even started to enjoy the Maybe fortunately, we did not chance to reverse it Somehow we could not see ourselv it through central London, but on an run from Birmingham to Glasgow it no worse than a normal 38-tonner. A long-haul, top-weight thinking oi where we see the Scania/Krone cone ing, running on restricted routes at times day or night.

60-tonne truck: The productivity bonus

• The Scan ia/krone outfit can take 3x7.82m containers.

• Potential cargo volume is 50% greater than a drawbar truck with a centre axle trailer (2x7.82m boxes and an overall length of 18.5m1.

• Cargo volume is 60% greater than with a truck and drawbar trailer (2 x 7.45m boxes and overall length of 18.75m).

• Cargo volume is 75% greater than with a conventional artic (with a 13.6m trailer and an overall length of 16.5m).

ID Based on a permissible new gross weight of 60 tonnes the gain in payload for the Scania/Krone combination is an impressive 50-60%.

The Scania/Krone concept rig also deals with the matter of congestion. As it can do the work of almost two artics the saving in roadspace is 5m—and that assumes no gap between the pair.

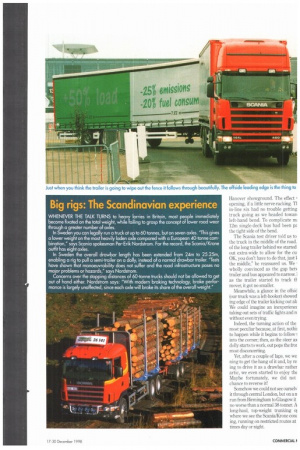

Big rigs: The Scandinavian experience

WHENEVER THE TALK TURNS to heavy lorries in Britain, most people immediately become fixated on the total weight, while failing to grasp the concept of lower road wear through a greater number of axles.

In Sweden you can legally run a truck at up to 60 tonnes, but on seven axles. 'This gives a lower weight on the most heavily laden axle compared with a European 40-tonne combination," says Scania spokesman Per-Erik Nordstrom. For the record, the Scania/Krone outfit has eight axles.

In Sweden the overall drawbar length has been extended from 24m to 25.25m, enabling a rig to pull a semi-trailer on a dolly, instead of a normal drawbar trailer. "Tests have shown that manoeuvrability does not suffer and the road infrastructure poses no major problems or hazards," says Nordstrom. Concerns over the stopping distances of 60-tonne trucks should not be allowed to get out of hand either. Nordstrom says: "With modern braking technology, brake performance is largely unaffected, since each axle will brake its share of the overall weight."

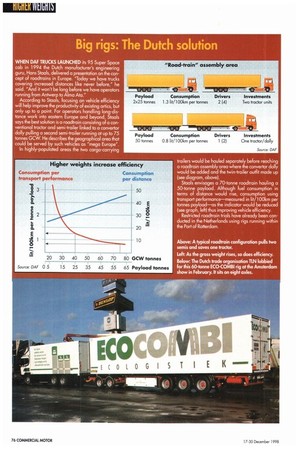

Big rigs: The Dutch solution

WHEN DAF TRUCKS LAUNCHED its 95 Super Space cab in 1994 the Dutch manufacturer's engineering guru, Hans Stoats, delivered a presentation on the concept of roadtrains in Europe. "Today we have trucks covering increased distances like never before," he said. "And it won't be long before we have operators running from Antwerp to Alma Ata." According to Stools, focusing on vehicle efficiency will help improve the productivity of existing artics, but only up to a point. For operators handling long-distance work into eastern Europe and beyond, Stools says the best solution is a roadtrain consisting of a conventional tractor and semi-trailer linked to a convertor dolly pulling a second semi-trailer running at up to 75 tonnes GCW He describes the geographical area that could be served by such vehicles as "mega Europe".

In highly-populated areas the two cargo-carrying trailers would be hauled separately before reaching a roadtrain assembly area where the convertor dolly would be added and the twin-trailer outfit made up (see diagram, above).

Stools envisages a 70-tonne roadtrain hauling a 50-tonne payload. Although fuel consumption in terms of distance would rise, consumption using transport performance—measured in lit/100km per tonnes payload—as the indicator would be reduced (see graph, left) thus improving vehicle efficiency.

Restricted roadtrain trials have already been conducted in the Netherlands using rigs running within the Port of Rotterdam.

60-tormers: Could we ever have them here?

The simple answer is: No chance. If there is one thing that unites the Great British Public it is a fear of heavy lorries. Despite the arguments, and the logic, it does not want them. And, given the nature of Britain's congested roads, that is hardly surprising. It's one thing to run a 60-tonne truck in the wide spaces of Australia or Sweden, it's quite another to suggest it in Britain.

But is the idea so fanciful? In the early 1970s the Department of Transport investigated the idea of the Double Bottom, a normal tractor hauling two semi-trailers using an A-framed convertor dolly. Fears over vehicle stability, particularly under braking, proved its undoing. But the advent of electronic braking has made the stability of large, multi-unit HGVs much more controllable. So where's the beef now?

Of course the environmentalists will continue to scream blue murder about the damage 60-tonne trucks would do to our roads. But the reality is that with more axles, the point loads are reduced—which is why the industry has asked for 44 tonnes on six axles, rather than 40 tonnes on five with an 11.5-tonne drive axle. You would have thought that even the most narrow-minded politician could grasp the logic of that argument The sheer size of a truck like the Scania/Krone concept rig would clearly tike some getting over. But it's only 925m longer than the longest drawbar and, running at night only on motorways, would anyone notice and shouldn't efficiency outweigh prejudice? The UK has the most highly trafficked roads in Europe. So wouldn't it make sense to tackle congestion by helping to reduce the overall number of vehicles on the road, including essential vehicles like HGVs?

The benefit of reduced emissions is hard to fault While engine manufacturers struggle to reduce levels of carbon dioxide and NOx in the next genera tion of Euro-3 and Euro-4 engines,

dieted deterioration in fuel e I linked with those reductions will1

any benefits in improved air After all, if cleaner engines bui fuel, where's the environmental Instead of having thous "green" 40 or 41-tanners make more sense to ha' 60-tanners hauling mo load, and producing le sions per tonne. As IV would say, "it's logi( tam". Perhaps the pn arguing for heavier t Britain is that, hist we have not asked 1 enough increase. haps we have sin thought it through]

Big rigs: The Australian approa

IN AUSTRALIA, MULTI-TRAILER ROADTRAI NIS are a common sight in the Outback, for long-haul, on-highway work there are twin-trailer artics known as B-Doubles. With an overall maximum length of 25m, and a gross weight of up to 63.5 tonn Australian B-Double is arguably the most productive and efficient line-haul truck face of the planet.

A typical modern version of an Aussie roadtrain has a relatively short, sp designed A-trailer with a fifth wheel behind the load area. This is coupled to the er—normally a standard 12.5m (41ft) or 13.7m (454) semi. Inaxle groupings on both trailers are the industry standard. Most B-Double operators spec an engine of about 500hp, along with an Eaton 18-speed overdrive box and a Rockwell or Eaton tandem-drive bogie. Running with a forward-control tractor, up to 34 pallets can be carried within the 25m overall length limit. Although US manufacturers such as Kenworth have dominated the 8-Double tractor market, European truck makers are beginning to make in For all its size and weight the B-Double has an exceptionally good safety recor must be fitted to the prime mover and,when hauling dangerous goods, on the trail Spray suppression equipment is mandatory along with a 100km/h road speed Trials have already taken place of the B-Triple—that's two A-trailers coupled to a st B-semi with a length of 33.5m and a gross weight of 77 tonnes. But in response to local traffic laws and environmental concerns. Australian roa and other extra-long outfits are seldom allowed to run in towns and cities. Instead t made up or divided down into smaller units at roadtrain assembly points outside main towns. These assembly areas are usually large lay-bys off the main highways

ii/ECO

11L.14111■ er=I=1=21 4100

Ear,t3

Ana

Above: Double-trailer B-trains are common down under

11'