ITALIAN BLUES

Page 35

Page 36

Page 37

Page 38

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

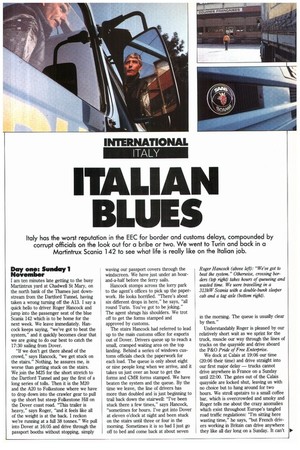

Italy has the worst reputation in the EEC for border and customs delays, compounded by corrupt officials on the look out for a bribe or two. We went to Turin and back in a Martintrux Scania 142 to see what life is really like on the Italian job.

Day one: Sunday 1 November

I am ten minutes late getting to the busy Martintrux yard at Chadwell St Mary, on the north bank of the Thames just downstream from the Dartford Tunnel, having taken a wrong turning off the A13. I say a quick hello to driver Roger Hancock and jump into the passenger seat of the blue Scania 142 which is to be home for the next week. We leave immediately. Hancock keeps saying, "we've got to beat the system," and it quickly becomes clear that we are going to do our best to catch the 17:30 sailing from Dover.

"If we don't get there ahead of the crowd," says Hancock, "we get stuck on the stairs." Nothing, he assures me, is worse than getting stuck on the stairs. We join the M25 for the short stretch to the Dartford Tunnel and pay the first of a long series of tolls. Then it is the M20 and the A20 to Folkestone where we have to drop down into the crawler gear to pull up the short but steep Folkestone Hill on the Dover coast road. "This trailer is heavy," says Roger, "and it feels like all of the weight is at the back. I reckon we're running at a full 38 tonnes." We pull into Dover at 16:05 and drive through the passport booths without stopping, simply waving our passport covers through the windscreen. We have just under an hourand-a-half before the ferry sails.

Hancock stomps across the lorry park to the agent's offices to pick up the paperwork. He looks horrified. "There's about six different drops in here," he says, "all round Turin. You've got to be joking." The agent shrugs his shoulders. We trot off to get the forms stamped and approved by customs.

The stairs Hancock had referred to lead up to the main customs office for exports out of Dover. Drivers queue up to reach a small, cramped waiting area on the top landing. Behind a series of windows customs officials check the paperwork for each load. The queue is only about eight or nine people long when we arrive, and it takes us just over an hour to get the forms and CMR forms stamped. We have beaten the system and the queue. By the time we leave, the line of drivers has more than doubled and is just beginning to trail back down the stairwell: "I've been stuck there a few times," says Hancock, "sometimes for hours. I've got into Dover at eleven o'clock at night and been stuck on the stairs until three or four in the morning. Sometimes it is so bad I just go off to bed and come back at about seven in the morning. The queue is usually clear by then," Understandably Roger is pleased by our relatively short wait as we sprint for the truck, muscle our way through the lines of trucks on the quayside and drive aboard the P&O Pride of Free Entoprise.

We dock at Calais at 19:06 our time (20:06 their time) and drive straight into our first major delay — trucks cannot drive anywhere in France on a Sunday until 22:00. The gates out of the Calais quayside are locked shut, leaving us with no choice but to hang around for two hours. We stroll upstairs to a small coffee bar, which is overcrowded and smoky and Roger tells me about the crazy anomalies which exist throughout Europe's tangled road traffic regulations: "I'm sitting here wasting time," he says, "but French drivers working in Britain can drive anywhere they like all day long on a Sunday. It can't be right. We wander downstairs at about 21:40 to find that the French guards have opened the barriers early and are allowing trucks onto the road although the national lorry ban is still in force. There is no question of queuing: it is first-come firstserved, and trucks regularly lose wing mirrors and gain scrapes in the scrtun. We head out of Calais and hit the main road at 21:52. The French guards have only made a token check at the gates, but the big red Scania next door has not been so lucky; as we pull away he is climbing from his cab to be checked thoroughly.

Between arriving at Dover just after 16:00 and leaving the Calais quayside just before 22:00, we have been off the road for four hours and 47 minutes, two hours and 51 minutes of which was taken up by customs formalities. As we join the A26 autoroute for Paris, ten minutes south of Calais, the police are waiting. Luck smiles on us again, but the two trucks ahead of us are pulled in as soon as they drive through the toll booths. The layby is full and the police have enough trucks on their hands for the time being: "Look at them," says Hancock, "we've all just come off the ferry and been checked twice over. They know that. It is just an easy place for them to nab a few people."

Day Iwo: Monday 2 November

It was a cold night. The cab heater was not working and our mood was not helped by the fact that the taps in the washroom in the Aire les Lisses would only supply cold water. "I hate shaving in cold water," says Hancock. After a hurried breakfast in the services we are on the road again. It is 10:30 and the sun is shining. We drive south down the A6 all day long. The road is called the Autoroute du Soleil by the French, and they turn it into a killing field on their first national holiday weekend every August. Not surprisingly, Hancock avoids the route that week.

By late afternoon we are doing well, heading for the Frejus Tunnel via the Tunnel du Chat, when disaster strikes. The Tunnel du Chat, the sign informs us, is closed, and we have to follow the diversion signs. Some 60km later we have almost come full circle and are back at the other end of the tunnel. Hancock is cross that the French authorities had not displayed any "tunnel closed" signs until we had more of less reached the tunnel and he is tired, having spent an hour more than expected "driving round a mountain I never even knew existed before today".

We finally arrive at the Frejus autoport at Modane. It is now mid, rather than early evening and we are worried that there will be a queue for customs. In fact the entire process takes just 13 minutes as the French look at the T2 forms, permits and transit advice slip. "That was good," says Roger, "it usually takes about an hour. In fact, I've queued up here for four hours at a stretch, just to get the forms stamped."

Over the CB, we pick up 'Monty' Murrel, another Martintrux driver. He sounds in a foul mood. We meet him and his daughter (who is travelling in the truck on her half-term holiday) in the autoport for a meal. He had picked up a load of exhibition goods in a groupage trailer on the Saturday morning, to bring them back to Britain. When he reached the Italian customs men at Frejus they told him that the carnet de passage had been filled in wrongly and he would have to go back to the main customs sorting area at Novara to have the trailer fully unloaded and rechecked.

On the way to Novara he was stopped by the police and told he was driving after 14:00 on an Italian national holiday so he would have to pay a 900,000 lira fine. "I haven't got it," said Monty. The police were prepared to bargain. "Have you got 250,000?" they asked, and when told no they reduced their demand further to 150,000 lira. They said they were unable to give him a receipt and they said they did not officially recognise the dispensation letter the border guards at Frejus had given him to return to Novara. Commercial Motor has a copy of that letter, signed by Enipeo Antonio Segretario on behalf of the Guardia di Finanza and dated 31 October 1987. It clearly explains: "This truck has just been resealed with a seal from this customs post and it is being forwarded to an internal customs office, where the re-exporting procedure will be dealt with." It lists the reasons why the truck had been refused permission to leave Italy. Monty was angry that the motorway police discounted it out of hand, despite the full explanation, the official stamp and the signature in favour of some cash in their pockets.

More was to come, however. Saturday is officially the day of the dead in Italy, so he could not be checked. Sunday was out too and he was unable to get anything done until 14:00 on the Monday afternoon. He finally got clearance from the Novara customs men at 17:00 and hurtled back to Frejus. "Sorry," said the Italians, there is a leak somewhere in the trailer which is dripping out from under the rear door. You are going to have to go back to Novara again. His despair was enough to get the Italian Guardia di Finanza in the mood for haggling. Eventually, they settled for a 100,000 lira bribe and waved him through. Just 50m further on he came to the French border guards who decided he did not have all of the right papers in the right order. They were ready to "boltup" (impound) the truck. Murrel haggled again and they agreed on a 100 franc bribe to allow him to photocopy a few of the missing papers. He finally got clear of the mess at about 21:00 Monday night. He is very tired, and very fed up. We leave him shortly before midnight and drive through the tunnel to park up for the night at a filling station on the Italian side of the Alps in Chiusa san Michele. Hancock stops on the pumps so that we will be woken early by the attendant.

Day three: Tuesday 3 November

We get our early morning call and are refuelled and on the road by 07:00, feeling tired and grubby. Since leaving home we have had only one opportunity to wash and shave, and that was in cold water, but Hancock's affable approach to everything that befalls him makes the hassles easier to take. He has a calm philosophical attitude to it all.

We reach our destination, Ventana Cargo on the outskirts of Turin, by 08:00 — the agreed delivery time. The loads are mainly parts for the Fiat car and aeroplane plants around Turin. We have 18 tonnes of Lucas Girling brake calipers on board and some high-value Rolls-Royce aerospace spares. A rude and disagreeable gateman refuses to let us pass inside the warehouse yard and we have to slot into a side road along with several other trucks. The gateman even refuses to let us use the toilet and is highly abusive. The Ventana agent takes our papers and says "wait here, we will be about 30 minutes." Four hours later he returns and says we must go to the central customs clearing compound in Turin, the Docks Piamontesi. The drive there is fraught, with Italian drivers going straight through red traffic lights as if they do not exist.

We park up in the docks and walk round to the offices of Sadi, the agents for Ventana. Roger wistfully says he could have come here first, if someone had bothered to tell us. We reach the Docks Piamontesi by noon.

Nothing much happens in Italy in the middle of the day. We fall foul of the torpor and the bureaucracy and have to wait for seven long hours while the invoices are cleared and stamped. There is, perhaps, 20 minutes work involved. The wait is made worse by the surroundings. Once in Piamontesi, the truck is effectively in quarantine and we can not go anywhere. The facilities for the hordes of waiting drivers are nil. Piarnontesi is a disused railway marshalling yard with nowhere to sit, nothing to eat, nothing to drink: there is not even a toilet and in the corners of the yard and behind some of the buildings the smell of the open sewer is overpowering.

In the late evening, after darkness, drivers have nowhere to wait at Piamontesi except on the steps of the main customs hall. Hancock, who has been standing in the hall of the building to keep warm, is ordered out onto the steps again. We finally get the torrns stamped and leave the docks just after 19:00. We have been waiting for customs clearance for a total of 11 hours. A full day's shift has been lost, Ventana's depot is closed and we are starving hungry.

That is the next problem. In Italy, says Roger, you cannot park wherever you like, it is dangerous. Thefts, fires, breakins and personal attacks go on all of the time, against any truck left overnight in an unprotected area. We decide to take an hour's drive out of Turin, to the Albergo (Hotel) Garrone at Carisio where the Italian family in charge are strongly rumoured to pay protection money. In any case, trucks are never tampered with.

When we arrive the place is packed with trucks from all over Europe. The food is excellent and we have our first hot wash since leaving Britain, 51 hours earlier. Over the meal we chat to Chris, a P&O Roadways driver we had met the previous evening at the Frejus Tunnel, and discover that he has had a frustrating day too. He had taken his Frans Maas tanker to a customs clearance compound in Turbigo and been kept waiting all day — over 12 hours. In the end, he had uncoupled the tanker in disgust, and driven his MAN 331 to Carisio for a meal. He knew full well that he would not be cleared at Turbigo until about noon the following day. Customs clearance Italianstyle for Chris was going to take more than 24 hours. He had been given 14:00 as his official slot, and if it took until then to clear the truck he would have been in Italy for 38 hours before getting clearance. "Every week we waste days, not hours, fatting about like this," says Chris. "Somebody really ought to do something."

Driving to Turbigo has its complications too. The city has imposed its own truck exhaust emission regulations and stops and tests lorries regularly in the market square. Drivers have to have a certificate to prove that they have been checked, otherwise it is another on-the-spot fine. To have the test carried out — you have guessed it — there is also a fee, this time of 5,000 lire.

Day four: Wednesday 4 November

Luxury of luxuries, Carisio provides us with a hot shower and a proper shave. We drive off to Ventana Cargo in Turin again to find the same foul-mouthed security guard. This time we have the correct paperwork and we drive in and unload the entire truck in one go. Roger is delighted — he will not have to tramp around the city to five or more different addresses. We phone home to find we are picking up a load from Beta Transport to Como. We charge up the A9 to Como and find the warehouse at about 15:30. They say they are "pleasantly surprised" to see us and we respond graciously. At 16:00 Emilio drives around the corner in his fork-lift truck and weighs us up. . five hours later he is still putting the finishes touches to the load. The first hour we sit and watch Emilio arguing with the boss about where to put what. They stroll off to sulk in separate offices for a while and then come out again for a good slanging match, during which Hancock lights a carefully rolled cigarette, sighs and smiles ruefully.

Day five: Thursday 5 November

After a quick coffee-and-bun breakfast at Aosta we head up into the sunny mountains. The road is busy and some of the holes on the Italian road up to Mount Blanc are horrific. One is so deep we are thrown completely clear of our seats and absolutely everything in the cab is thrown across the floor. We grovel about picking up coins and combs. The Italian customs point at Mount Blanc takes exactly three minutes to transit and the French customs at Cluses only a minute longer.

Day six: Friday 6 November

We rise early, fill up with fuel and set out with a purpose. The garage stop has been an irritation which, if it were not for another European legislative anomaly, would not have been necessary. Drivers going into France cannot carry more than 300 litres of diesel. It is a cute con. To transit a country as large as France with only 300 litres in the tank it is obvious that you are going to fill up on route.

We bypass Paris to the east taking the "Ho Chi Min trail." "All of us British drivers call it the Ho Chi Min trail," says Hancock. "Why?" [ask. "Durmo."

Disaster strikes again, this time in the guise of a blown trailer tyre. Try as he might, Roger cannot crack the wheelnuts and we have to pull into a small garage at Bray-sur-Seine. The owner, Veljkovic Rocho, is as nice as pie. He even drives us down to the local cafe for breakfast. It is bitterly cold. He returns as promised after an hour, and gives us a bill that far exceeds the cash we have between us. Hancock's Michelin European Breakdown tyre repair scheme proves unacceptable too so we offer a credit card. "Non," says Monsieur Rocho, so we try another brand. Luckily, the Visa card is acceptable and we can get underway again. Having been further delayed by dense fog we reach Calais to board the 18:15 ferry and reach Dover at 19:05 British time. We get stuck in the P&O hold for' nearly 30 minutes because the bow ramp refuses to lower. When it finally does, we select lane eight and head straight for the Dover immigration building. We write our names on two pink cards, hand them in and go through the "Anything to declare process." Dover is the first international border I have crossed all week which wants to see my passport.

We park up and dash to the customs clearance building. Hancock is hoping that the random selection process will allow our four entries to go through the new checking process with the minimum of fuss. The different clearance "routes" vary from a full inspection of the truck and trailer to little more than stamping the bits of paper. Our worst nightmare comes true. The computer has gone down, nothing much is happening and the customs men cannot tell us when our turn is likely to come because of the chaos the computer failure has caused. "Not again," says Hancock. We trudge into the Wheelhouse, a sort of clubhouse with a video room and bar. Hancock disapproves of the bar. "Soft drinks yes," he says. "Hard booze no. Not when the lads are sitting around like tonight, bored — it is dangerous."

We could stay up to wait for the clearance message to appear on the television screens in the Wheelhouse. We could rent a Telecom bleeper which rings when clearance is complete. We do not have sufficient heart or interest to do either so we go to bed. Apparently, we are told the next morning, clearance came through just before 01:00. Three of the entries went route three, the other went route one. Clearing Dover customs takes five hours and 45 minutes. We head for home.

Talk to any group of British truckers anywhere on the Continent and it is the same story: they feel aggrieved. Overseas they face literally hundreds of different operating restrictions and local regulations which non-British drivers working in the UK do not face. They cannot drive in France, Germany or Italy on Sundays and bank or national holidays from 22:00 or midnight the previous evening to the same time on'the day itself; they cannot take full fuel tanks into countries like France; they are constantly pulled up for roadside permit checks which they say are far more stringent than those in the UK; they are pestered by corrupt police and customs officials looking for bribes; they work out of a country whose government is too weak to win them the permits they need (though that seems to be changing); they must avoid local truck bans in towns such as Chalons-sur-Soane, Bourg-enBresse, or Bethieu; they are stopped and forced to pay at a never-ending stream of motorway toll booths when all of Britain's motorways are free; they must handle foreign loading agents with no idea of axle weight rules in the UK or the 38-tonne overall limit; and they have a sneaking suspicion that whenever there is a queue for clearance, they seem to come out last.

Ask them whether they think the EEC will get its act together and harmonise all of these rules by 1992, or whether the EEC has already made their lives and their jobs any easier, and they just laugh in your face.

ID by Geoff Hadwick