Choose Your Ax] or Fuel Economy

Page 44

Page 45

Page 46

Page 47

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

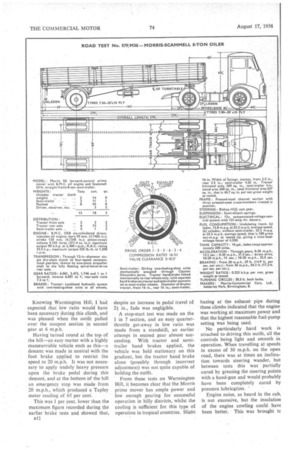

Morris Oil-engined Tractor, Running at Almost 14 tons Gross, Puts Up Good Performance Despite Overload : Short Wheelbase Gives Outstanding Manauvrability By John F. Moon,

A.M.I.R.T.E.

HAD a two-speed axle or a close-ratio five-speed gearbox been fitted to the Morris oilengined prime mover which I recently road-tested, its fuel economy, at nearly 14 tons gross, would have been much improved. Although the laden figure returned during the tests was not as "good as I had expected, the prime mover was in standard trim for running at a gross train weight of 11 tons and was not wholly suited to an 8+-ton test load.

Other than the fuel consumption, the performance of the Morris tractor, despite its diminutive size, came up to a high standard. Articulated outfits are well known for giving a high degree of manoeuvrability at the best of times, but the Morris outfit is exceptional in this respect, the 7-ft. wheelbase of the prime mover allowing a turning circle of 30+ ft.

Ample Power The good torque characteristics of the B.M.C. oil engine provide ample power for hill climbing and acceleration, whilst driver comfort has not been forgotten.

Several versions of the tractor are offered. With a standard 7.2 to 1 ratio single-speed rear axle and 7.00-20-in. (10-ply) tyres, it is recommended for use with 6-8-ton semitrailers at a. gross train weight of 11 tons.

This • gross weight figure is increased to 12 tons when the tractor is fitted with 7.50 tyres. With an Eaton 13500 two-speed axle and 8.25-20-in. (12-ply) tyres, it may be employed at 15 tons gross weight.

As the test vehicle was used in conjunction with a semi-trailer heavier than normal and an 84-ton test load, it should have had an Eaton axle or the test load should have been reduced by nearly 2 tons.

I decided to test it overladen, however, to give a clear indication of the engine power available, bearing in mind that in all probability the prime mover would be running in service at this weight at least,

With only four speeds in the gearbox and a single-speed axle, the tractor was placed at a disadvantage on the undulating route used during my fuel-consumption tests, in that gradients in the region of 1 in 10, such as are frequently found on main trunk routes, necessitated the use of second gear. A close-ratio five-speed box (which is not offered by the manufacturers) would have made matters easier, whilst a two-speed axle, giving split ratios, would have allowed the same speed performance at lower fuel cost.

The chassis specification of the prime mover follows closely that of the current 5-ton forward-control long-wheelbase chassis, the -principal difference being that a one-piece propeller shaft is used because of the shortened wheelbase. As an alternative to the B.M.C. 0E13 90 b.h.p. oil engine, the chassis is available with an 87 b.h.p. six-cylindered petrol engine, It is suitable for several makes of

semi-trailer coupling, the test vehicle having Scamme11 equipment. The ramps which form part of this equipment require the rear of the frame longitudinal members to be downswept and the rearmost cross-member to be omitted. This cross-member is 'retained with most other coupling gears.

A Scammell 23-ft. straight-frame 8-ton -semi-trailer was used for the test. This was from the MorrisCommercial works transport fleet and was fitted with a timber dropside body. In normal service this semi-trailer carries oil engines between the various factories in the B.M.C. organization, thus the timber floor was covered with 12 s.w.g. steel sheet. It was therefore heavy for one of only 8-ton capacity.

Concrete blocks totalling 81 tons were loaded down the centre of the body in pairs. The foremost of these blocks was loaded up against the semi-trailer headboard, with the result that the imposed load did not extend beyond the semi-trailer axle.

When checked on the weighbridge, the tractor rear axle was found to be carrying more than the semi-trailer axle and was much overloaded. The front axle loading was low, being only 2 tons 31cwe with myself and Mr. J. Lane in the cab.

Having attached a calibrated test tank to the vehicle and inflated the

tyres to 85 p.s,i., the outfit was driven to the Chester Road, Castle Bromwich, for braking and acceleration trials.

The average figures returned from brake tests made from 20 m.p.h. and 30 m.p.h. were fully satisfactory, particularly as it afterwards transpired that none of the brakes had been adjusted recently. The average Tapley meter readings of 50.5 per cent., which were achieved during the emergency stops from 20 m.p.h., showed that the maximum deceleration was close to the average of 0.465g, which suggested that there was little time-lag in the system There was a greater difference between the maximum average deceleration rates when braking from 30 m.p.h., but this would be caused by slight locking of the tractor rear wheels and, on one occasion, the semi-trailer wheels.

During all these brake tests maximum pedal pressure was used and the outfit came to rest in a •straight line on each occasion with no tendency towards veering or jackknifing.

The good torque characteristics of the engine were demonstrated to the full during the 'accelerationtests, particularly on the direct-drive runs made from 10 m.p.h. Second gear was used when pulling away from a standstill, during the 0-30 m.p.h. tests. The torque curve of the engine is such that on level ground it should normally be unnecessary to change out of top gear until the road speed falls well below 15 m.p.h.

A 12.6-mile stretch of the A41 road between the outskirts of Warwick and the foot of Warmington Hill was used for the fuel-consumption tests. This course was covered in each direction to give average figures. The road is heavily undulating in a southerly direction and its hilly nature is reflected in the difference of fuel-consumption figures returned.

On the outward run from Warwick, a consumption rate of 11.2 m.p.g. was •achieved, whilst on the return run this figure was improved to 14.9 m.p.g., the average speeds being virtually the same in each direction. During the outward run, it was necessary to use second gear for two minutes on a 1-in-I 0 incline, and third gear for the same length of time on a 1-in-14 gradient.

From these -figures it will be seen that, whilst the use of a two-speed axle is to be advocated when running at over 13 tons gross, it is not essential if the prime mover is to be operated over reasonably level country. Average consumption rates of at least 14 m.p.g. should then be feasible, and these could be further improved with a higher-ratio axle.

Fuel Consumption Differences

After disconnecting the semitrailer, a second series of runs was made, the road speed being kept down so as to produce an identical average speed for the out and return journeys as when running laden. Even when unladen, there was a difference in consumption rates of 1 m.p.g. between the two journeys, although top gear was engaged throughout both trips.

This unladen test was made because some operators find it necessary at times to run their tractors between depots without semi-trailers, and it will enable them to gain some • idea of the overall fuel performance under mixed conditions.

Between these two laden fuelconsumption runs, hill-climb and brake-fade tests were conducted on Warmington Hill. This quarter-mile .climb hai a general gradient of I in 9 and a maximum gradient of 1 in 7.

At the bottom of the hill. the vehicle was stopped and the radiator temperature was recorded as 170° F., the ambient temperature being 76° F. A fast climb was then made in 3 minutes and at the summit a second reading revealed that the coolant temperature had risen by 16° F. Knowing Warmington Hill, I had expected that low ratio would have • been necessary during this climb, and was pleased when the outfit pulled over the steepest section in second gear at 6 m.p.h.

Having turned round at the top of the hill—an easy matter with a highly manoeuvrable vehicle such as this—a descent was made in neutral with the foot brake applied to restrict the speed to 20 m.p.h. It was not necessary to apply unduly heavy pressure upon the brake pedal during this descent, and at the bottom of the hill an emergency stop was made from 20 m.p.h., which produced a Tapley meter reading of 65 per cent.

This was 1 per cent, lower than the maximum figure recorded during the earlier brake tests and showed that, B12 despite an increase in pedal travel of 2-1in., fade was negligible.

A stop-start test was made on the 1 in 7 section, and an easy quarterthrottle get-away in low ratio was made from a standstill, an earlier attempt in second gear almost succeeding. With tractor and semitrailer hand brakes applied, the vehicle was held stationary on this gradient, but the tractor hand brake alone (possibly through incorrect adjustment) was not quite capable of holding the outfit, From these tests on Warmington Hill, it becomes clear that the Morris prime mover has ample power and low enough gearing for. successful operation in hilly districts, whilst the cooling is sufficient for this type of operation in tropical countries. Slight hazing at the exhaust pipe during these climbs indicated that the engine was working at maximum power and that the highest reasonable fuel-pump setting was being used.

No particularly hard work is attached to driving this outfit, all the controls being light and smooth in operation. When travelling at speeds in excess of 30 m.p.h. on the open road, there was at times an inclination towards steering wander, but between tests this was partially cured by greasing the steering points with a hand-gun and would probably have been completely cured by pressure lubrication.

Engine noise, as heard in the cab, is not excessive, but the insulation of the engine cowling could. have been better. This was brought tc light during the tests because of the relatively high ambient temperature, and when first noticed it led me to suspect that the engine was overheating, although a subsequent temperature check proved that the water temperature was only 170°F.

This characteristic is accentuated by the shape of the cowl, which allows a pocket of hot air to build up against the rear vertical panel.

Maintenance of the prime mover proved to be reasonably simple, most of the Components which require regular attention being readily accessible. Using the screw jack of the tool kit, adjustment of the four brakes took just under 20 minutes, whilst bleeding occupied 9 minutes.

Removal of the upper section of the engine Zowl gives access to the radiator and engine-oil dipstick, which were noted in 8 and 15 seconds respectively. With this cowl already removed the tappets were checked and adjusted in 25 minutes. During this operation the engine was turned over by means of the electric starter.

The oil-bath air cleaner is mounted directly on the throttle venturi, and was dismantled and reassembled for a level check in 1 minute 20 seconds. An injector was changed in under 5 minutes, which indicated that the complete set could be removed and replaced in well under half an hour.

The Morris oil-engined tractor is a welcome addition to the current ranges of Medium-weight prime movers made in Great Britain. It sells at a basic price of £1,059, plus £217 17s. id. purchase tax.

My tests do, however, emphasize the importance, when ordering, of specifying the use to which the prime mover is to be put. Given the right gearing, it could have an overall performance which would put it in the forefront of its class in respect of economy and working capacity.