SYSTEM IN MAINTENANCE AN1

Page 32

Page 33

Page 34

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

COSTING SPELLS SUCCESS S.T.R.

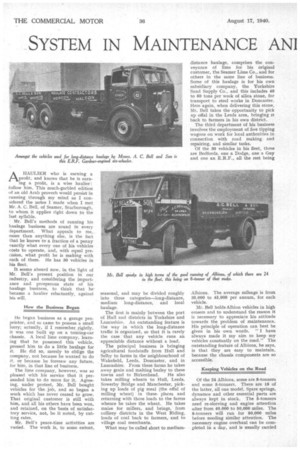

Experience of a Progressive Yorkshire Haulier Who Applies Original Methods to his Maintenance, his Tyre Selection and his Payment of Wages to his Drivers AHAULIER who is earning a profit, and knows that he is earning a profit, is a wise haulier : follow him. This much-garbled edition of an old Arab proverb would persist in running through my mind as I considered the notes I made when I met Mr. A. C. Bell, of Seamer, Scarborough, to whom it applies right down to. the last syllable.

Mr. Bell's methods of running his haulage business are sound in every department. What appeals to me, more than anything else, is the fact that he knows to a fraction of a penny exactly what every one of his vehicles costs to operate, and, with equal precision, what profit he is making with each of them. He has 30 vehicles in his fleet.

It seems absurd now, in the light of Mr. Bell's present position in our industry, and considering the importance and prosperous state of his haulage business, to think that he became a haulier reluctantly, against his will.

How the Business Began He began business as a garage proprietor, and so came to possess a small lorry; actually, if I remember rightly, it was one built up on a touring-car chassis. A local lime company, learning that he possessed this vehicle, pressed him to do a little haulage for it. Be did so, merely to oblige the company, not because he wanted to do it, or because he foresaw any future, for him, in that line of business.

The lime company, however, was so pleased with his service that it persuaded him to do more for it. Agreeing, under protest, Mr. Bell bought vehicles for the. job, and so began a work which has never ceased to grow. That original customer is still with him, and all his others have been won, and retained, on the -basis of satisfactory service, not, be it noted, by cutting rates.

Mr. Bell's peace-time activities are varied. The work is, to some extent, seasonal, and may be divided roughly into three categories—long-distance, medium long-distance, and local haulage.

The first is mainly between the port of Hull and districts in Yorkshire and Lancashire. An outstanding feature is the way in which the long-distance traffic is organized, so that it is rarely the case that any vehicle runs an appreciable distance without a load.

The principal business is bringing agricultural foodstuffs from Hull and Selby to farms in the neighbourhoodof Wakefield, Leeds, Doncaster, and in Lancashire. From these farms he takes away grain and malting barley to these towns and to Birkenhead. He also takes milling wheats to Hull, Leeds, Sowerby Bridge and Manchester, picking up loads of pig meal (the offal of milling wheat) in these places and returning with those loads to the farms whence he takes the wheat. He takes maize for millers, and brings, from colliery districts in the West Riding, loads of coal back to farmers, and to village coal merchants.

What may be called short to medium distance haulage, comprises the conveyance of lime for his original customer, the Scorner Lime Co., and for others in the same line of business. Some of this haulage is for his own subsidiary company, the Yorkshire Sand Supply Co., and this includes 40 to 80 tons per week of silica stone, for transport to steel works in Doncaster. Here again, when delivering this stone, Mr. -Bell takes the opportunity to pick up offal in the Leeds area, bringing it back to farmers in his own district.

The third department of his business involves the employment of five tipping wagons on work for local authorities in connection with road making. and repairing, and similar tasks.

Of the 30 vehicles in his fleet, three are Bedfords, one a Dodge, one a Guy and one an E.R.F., all the rest being Albions. The average mileage is from 35,000 to 45,000 per annum, for each vehicle.

Mr. Bell holds Albion vehicles in high esteem and to understand the reason it is necessary to appreciate his attitude towards the problem of maintenance. His principle of operation can best be given in his own words. "I have always made it my aim to keep my vehicles constantly on the road." The outstanding feature of Albions, he says, is that they are easy to maintain, because the chassis components are so accessible.

Keeping Vehicles on the Road Of the 24 AIbions, some are 8-tonners and some 5-tonners. There are 18 of the latter, all one model, Spare springs, dynamos and other essential parts are always kept in stock. The 5-tonners need re-sleeving and engine attention after from 40,000 to 50,000 miles. The 8-tonners will run for 80,000 miles before needing similar attention. The necessary engine overhaul can be completed in a day, and is usually carried out on Sunday. Amongst the spares, Mr. Bell keeps complete axle units, and these can he interchanged in a couple of hours.

At one time he had some trouble with cracked cylinder blocks. Whilst that trouble lasted, he discovered the value of " Wondar Weld," a preparation which is poured into the cylinder jackets, and seeps through the cracks, where it is deposited until it fills the fracture.

There is a further reason for this preference for Albions. Again I think I should quote Mr. Bell's own words. He says, " Albions make profits." Having made that statement he proceeded to show me figures for the operation of an 8-tonner with a Gardner oil engine. This vehicle cost, originally, -21,000 and is covering approximately 40,000 miles per annum. The average earnings per mile are almost exactly those recommended in " The Commercial Motor Tables of Operating Costs."

Good Costing Arrangements The cost of operating this vehicle is rather less than the figures quoted in "The Tables" and the net profit, therefore, is rather better than that which is therein specified. It would, obviously, be unfair to give, in detail, these figures for costs and earnings. What is of interest, however, is that in examining his books, while we were discussing the performance of this particular vehicle, I found that his method of keeping costs was similar to that -which I have so often recommended.

It was particularly so in the two aspects which I have so often stressed. The costs of each vehicle are taken out separately, and anything which cannot positively be debited to vehicle operating costs is entered as overheads. Mr. Bell finds that a reasonably accurate assessment of the overheads throughout his fleet is on the basis of 95. 6d. per week per ton of carrying capacity.

Particular care is taken with the recording of tyre costs. An account book is set aside especially for this purpose, and each tyre has its own page. Every tyre is booked out to the vehicle to which it is fitted, and removal and replacement are entered just as accurately. Whenever a driver replaces a tyre, he must make a note of the fact on his time sheet, together with a record of the mileage shown on the speedometer at the time when the change is made.

Mr. Bell makes the unusual claim that petrol-engined vehicles are more costly in respect of tyres than are oilengined machines. He attributes this to the fact that all his oil engines are governed, whereas the petrol engines are not. My own conclusion is that it is speed rather than type which is the factor of importance, and that if the petrol vehicles be kept to a limit of road speed equivalent to that of the oilers, the tyre wear would be the same on each.

Mr. Bell considers the extra lowpressure tyre to be ahead of all others in the service it gives and the economies it affords. He has found that vehicles so equipped cost less in chassis maintenance; there is less trouble arising from stones being picked up between twin tyres; they do not heat so much, and they are more reliable when retreaded.

At one time, his 8-ton vehicles were equipped with 36-in. by 8-in, heavy

duty covers. The mileage per tyre was usually around 12,000, but sometimes it was as little as 7,000. ise replaced those tyres by 10-.5-in. by 20-in, extra low-pressure equipment, and now obtains as many as 30,000 to 35,000 miles per tyre on rear wheels, and 50,000 to 60,000 miles on front wheels. The 36-in. by 8-in. tyres used to cost £10 5s. 10d. each and the 10.5-in, by 20-in. £14 5s. 4d. each. This means that with the heavy-duty tyres his cost per mile per tyre was in the neighbourhood of id. It is now reduced to one-tenth of a penny.

He is of opinion that, to ensure the best results, and to obtain the maximum of economy in tyre cost, certain fundamental principles must be kept in view. In the first place a new cover is never fitted alone: it is always accompanied by a new tube. Tyres are never so fitted that twins do not match. In Mr. Bell's view it is fatal to mate a new tyre with an old one on a wheel carrying twin tyres. Tyres are always retreaded once, but only by the makers. In his experience, a retreaded tyre gives about 50 per cent. of the mileage of a new one.

Bonus System Effects Economy Mr. Bell is, again, interesting on the subject of wages. He has for a long time had in operation a bonus scheme for his drivers, which, he says, has reduced his vehicle requirements by 33* per cent. He is of opinion that he would need 45 vehicles to do the work which he now does with 30, if this drivers' bonus system were not in operation.

The method of calculating this bonus is novel, and sound in principle, especially in the case of a haulage contractor operating under such conditions as those of Mr. Bell's vehicles. He calculated that he could afford to pay , every driver 4s. 6d. for every 21 earned by a vehicle. He assesses his bonus on that basis, and prior to the fixation of wages, used to pay his men on that scale.

When wages were fixed he had to modify his system, and he did so by continuing to grade the men on the old basis, paying them the agreed wage throughout the year, and the bonus at the end of the year, according to earnings, calculated with the old scale as a basis.

He showed me a schedule of bonuses paid during the previous year. It varied, per man, from a minus quantity to a maximum of 254; the minus quantity is not deducted. The list of bonuses is pinned up in the office at each depot for all the men to see.

The result is a considerable economy in working, but the method has one defect which it is sometimes difficult to overcome, in that drivers on, say, short to medium-distance haulage of high tonnage, where the loading and unloading are easy, and the earnings per day are considerable, have an advantage over others who are not so favourably situated. This is overcome, to a certain extent, by changing the men from one job to another in so far as that is practicable.

A reference may be made to one experience of Mr. Bell's—an experience not necessarily confined to him, but which, in a way, has been emphasized in connection with traffic in grain, milling wheat, barley and similar commodities.

In discussing the keeping of costs and in demonstrating to me how carefully that was done, he made particular reference to the figures relating to the delivery of sacks when returned empty. In his experience this is a most important item. Sacks are worth Is. each. Farmers are careless with them and often say they have returned them, and insist on being given credit for them when, as a matter of fact, they have been mislaid. He says that one firm, for which he works, used to expect a loss of as much as £500 per annum on sacks not returned. • Mr. Bell, in his business, takes full responsibility for sacks, and the firm's agent may now confidently refuse to allow a farmer credit for empty sacks, unless Mr. Bell's records show that the farmer has delivered them to him. Every consignment of sacks must be signed for by Mr. Bell's drivers.

There appears to be no doubt that Mr. Bell has bunt up a successful business on the basis of sound service and on system, both in recording costs and iia maintaining his vehicles.