FINANCING PUBLIC SERVICE TRANSPORT.

Page 45

Page 46

Page 47

Page 48

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

An Interesting Survey of the Growth and Development of the Motorbus Industry, with a Review of the Capital Employed and the Earnings.

IfrifIE ,history of mechanical transport in public _L service reproduces many of the familiar features of British industries. Our national habit is to treat innovations with hostility, to put every possible difficulty in the way of pioneers and then to accept the benefits conferred by the innovations grudgingly at first and, later, with the alternate indifference and criticism due to a facility which has become a commonplace.

The story of the steam carriages tried on British roads in the early part of the 19th century has often been told, and it must be admitted that public hostility was then successful in destroying an industry in embryo. It is an attractive, but doubtless futile, speculation to estimate how mechanical traction on roads would have developed if legislation had not then placed its ban upon the steam carriage. Such speculations, however, can find no proper place in this chronicle of finance, although it will be necessary to refer to the development of the public-service motor which followed upon the change to a more enlightened legislative policy in 1896. and to indicate the several routes along which the motor omnibus has made its way into public favour.

Its first and main entrance was by way of replacement of horse omnibuses on 'existing services. Other avenues of approach in .due course presented them-. selves in the development of inter-urban and rural services, either in connection with railWays or indepen" deutly ; the supplementing: of. tramway services along busy routes ;.,-.the feeding of tramway and railway (" tube ". and other) services by the Provision of motor omnibus facilities over new routes; the .establishment of motor omnibus services in small towns, and the supersession of the old type or country carriers.

In such circumstances, as may be realized, the prosaic chronicler of statistics meets with insuperable difficulties, and, in consequence, the complete and detailed early history of motor finance, unlike the rival transport services of railways and tramways, has never been compiled. The first comprehensive financial and commercial record of the British mechanicalroad transport industry* did not make its appearance until 1916.The record is now brought up to date annually. The story of the early years, however, can be told in broad outline from the development record of the publicservice motor, which may conveniently be divided for the purpose into three periods :-(1). 1.897-1904; (2) 1905-1911; (3) 1912 to the present day.

In 1.897, after banishment for nearly 60 years, the

• mechanically propelled omnibus-this time an electric one-reappeared upon. the streets of London, to be followed by an oil-motor vehicle in .1899. It stayed there barely a year, but it foreshadowed the dawn of a new era! Other experimental services with steam omnibuses w7ere made in London and elsewhere, but no great amount of sutcess was obtained. Electrification of tramway systems was proceeding apace, against which it was thought-and justifiably at the time-no motorbus could compete. • In July, 1900, the "Twopenny Tube-" was openeda competitor of such serious moment to the predominant omnibus concerns that it undoubtedly served to quicken the interest of those responsible for them in the development of motor traction; and, with other electric railway projects in view, it was felt by some people that the long-continued prosperity of the horse omnibus was drawing to a close.

The year 1901 saw 3,736 horse omnibuses on the roads of London-II figure doomed to dwindle to ultimate ex Unction ; and so we draw to the close of the first period, but the total capital sunk in these experimental motor services is unrecorded. At the end of 1903 the number of mechanical power buses at work in London was 13, of horse buses 3,623; and, since the horse omnibus concerns were now to take a leading part in introducing the passenger motor vehiele, it may be of interest to give here Some particulars as to the capital at that time of the most important companies.

London General Omnibus Co., Ltd. Registered November, 1858. Capital authorized, £1,000,000. Capi

tal issued, £773,592. Loan capital, £300,000 (4 per cent.). Dividends paid, 1899 and 1900, 101 per cent. ; 1901 and 1902, 51 per cent.; 1903, 71 per cent_ London Road Car Co., Ltd. Registered January

• 1st, 1883. Capital authorized, £500,000. Capital issued, , £384,000. Loan capital, £150,000. Dividends paid, 1899, 9 per cent. ; 1900, 71 per cent.; 1901, 3 per cent.; 1902, 5* per cent.; 1903, 61 per cent.

Star Omnibus Co., Ltd. Registered March 14th, 1899. Capital authorized, £275,000. Capital issued, ordinary, • £125,000; 51 per cent. preference, £150,000. Dividends paid, 1899 and 1900, 10 per cent.; 1901, 5 per cent.; 1902, nil ; 1903, 5 per cent.

. ASsociated Omnibus Co., Ltd. Registered November 27th, 1900. Capital authorized, £150,000. Capital • issued, £135,000. Dividends paid, 1901, 6 per cent.; 1902; 5 per cent; 1908, 8 per cent.

London (Minibus Carriage Co., Ltd. Registered January 30th, 1886. Capital authorized, £60,000. Capital issued, £17,130. Loan capital, £6,200 (5 per cent.). Dividends paid, 1899 and 1900, 81 per cent.; 1901 and 1902, nil; 1903, 21 per cent.

Other important companies ooerating in London at the close of 1903 were Thos. Tilling, Ltd., Birch Bros., Ltd., and among•private owners Messrs. Cave, Clinch, French, Glover and Hearn, the capital employed by the companies amounting to approximately £3,000,000.

Outside London, among the companies operating horse buses may be mentioned the Brighton, Hove and Preston United Omnibus Co., Ltd., with a share and loan capital amounting to £31,700. the Dundee Tramways and Carriage Co.' Ltd., with +38,979, the Provincial Tramways Co. at Cardiff and Gosport, the Edinburgh Street Tramways .Co. (25 buses running) and the British Electric Traction Co., the latter operating over some 72 miles of omnibus routes in various districts.

It was at the close of this period also that we witnessed the rapid decline of the horse tramway systems and their conversion to electric traction. Fourteen electric-traction systems were in existence in 1895, four new ones started in 1896, two in 1897, nine in 1898, twelve in 1699, twelve in 1900, twenty-five in 1901 and eleven in 1902. Here we have a bird's-eye view of the early development period of the electric-traction industry. In 1904 the capital invested in 156 electrictraction companies amounted to nearly £62,000,000, and the average rate of dividend paid by 77 of the companies on an aggregate capital of £48,789,525 was 4.41 per cent. The amount of money spent by 92 niunieipalities on electric tramways was £21,295,771, the total inwstment in the industry amounting, therefore, to approximately £83,000,000.

The Coming of the Motorbus.

These figures indicate the financial strength of the rival systems prevailing at the opening of the second phase of motorbus development. It was customary in many quarters then to speak confidently of the "coming of the motorbus," and a spirit of optimism took possession of those charged with promoting the welfare

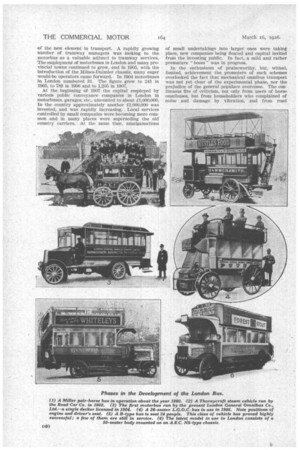

of the new element in transport. A rapidly growing number of tramway managers was looking to the motorbus as a valuable adjunct to tramway services. The employment of motorbuses in London and ninny provincial towns continued to grow, and in 1905, with the introduction of the Milnes-Daimler chassis, many eager would-be operators came forward. In 1904 motorbuses in. London numbered 31. The figure grew to 241 in 1905, to 783 in 1906 and to 1,205 in 1907.

At the beginning Of 1907 the capital employed by various public conveyance companies in London in motorbuses, garages, etc., amounted to about £1,000,000. In the country approximately another £1,000,000 was invested, and was rapidly increasing. Local services controlled by small companies were becoming more common and in many places were superseding the old' country carriers.: At the same time, amalgamations

of small undertakings into larger ones were taking place, new companies being floated and capital invited from the investing public.' In fact, a mild and rather premature " boom " was in progress.

In the enthusiasm of praiseworthy, but, withal, limited, achievement the promoters of such schemes overlooked the fact that mechanical omnibus transport was not yet clear of the experimental phase, nor the prejudice of the general populace overcome. The Om= tinuous fire of criticism, not only from users Of horse omnibuses, but from householders who complained of noise and damage by vibration, and from road

authorities. regarding the increased wear and tear of road surfaces, cont, pelled the licensing authorities to take action-and the year 1908-1909 were disastrous ones. Crushed by the burden of expense incurred in endeavmrs to bring their fleets up to requirements, company after company succumbed from financial embarrassment, others withdrew their vehicles and bent their 'energies in new directions, until only. two companies remained in London, viz., the IAmdon General group and Thos. Tilling, Ltd., and these had corn" rnenced to design and produce their own vehicles.

In 1910 the L.G.O.C. produced. the first chassis of their own design and manufacture known as the " B "

type. Other British makers ,had also been aroused, and Dennis, Leyland, Straker. and Thornyeroft were , forging forward to a conspicuous place in road trans. port history. The public watched the disappearance of the earlier buses and the advent of the new types with gratitude. In 1010, for the first time in London's history, motor omnibuses were more numerous than horse buses, the figures being 1,200 motorbuses and • 1,103 horse buses. The corresponding figures in 1911 were : motorbuses 1,962, horse buses 786. The business was now practically in the hands of five companies, viz.. the L.G.O.C. group, Thos. Tilling, London Central Motor Omnibus, Metropolitan Steam Omnibus and the National Steam Car. The number of passengers carried by these in 1911 was 490,628,487, which may be compared with 821,819,741 then carried by tramways.

The Triumph of the Motorbus.

The third phase commences with the triumph of the British commercial vehicle manufacturers, who, though slow in starting, had now beaten the world in design. Motorbuses, conspicuously. reliable in operation, made their way. into, public services throughout the country, these, for the first time,perhaps, were entitled to be classed as an "industry." Then the war intervened to deplete those services and to prevent the formation of new enterprises. But the stimulus which the war ultimately gave to mechanical transport is too well known to he recounted. • It is the history of our own times.

Hitherto,. we have been compelled to tell our story • mainly in the light of London's experience. Although London vkias the centre Of motorbus development, the • provinces also played an important part. That wonderful provincial organization, the Birmingham and Midland Motor Omnibus Co., Ltd., was at work as early as May, 1904. The Eastbourne Corporation, obtaining an Act of Parliament in 1902, commenced service in 1904, and was:One of the first municipalities to operate. The G.W.R. pioneered the railway companies with several services in 1.903. But collated statistics of these early years are lacking; nothing had been done to provide a• comprehensive financial and statistical record of the mechanical road transport undertakings throughout the country.

In 1915-16 "The Motor Transport Year Book and Directory" was compiled to fill this gap,' being issued by the Electrical Press, Ltd. The story of road transport finance thenceforth can be told with comparative completeness, and the story reveals a.n'e.ver-increasing employment of all forms of power transport. Starting, in 1015-16 with 218 companies, 44 private firms and 96 nmnicipalities-358 in all-the record in 1924-25 shows a total of 3,222 motor transport concerns, viz., 1,765 companies, 1,352 private firms and 105 municipalities. _ A. preliminary survey of the returns for 1925-26 shows, as may be expected, a considerable increase on these figures.

The capital invested in the industry, which in 1915-16 stood at approximately £9,764,000 (including £141,000 expended by municipalities) had grown to £27,071,000 (including £1,472,000 expended by. municipalities) in

1924-25. The corresponding total for 1925-26 will undoubtedly exceed £30,000,000, an increase of £20,000,000 in a period of ten years. The figures, of course, are minimum figures, and do not include the capital expended by a large number of one-man concerns, of which particulars are unobtainable.

The progress made from year to year may best be shown in tabular form. Table .No. I (above) sum• marizes the amount of capital authorized and invested for the period 1915-16 to 1925-26 as recorded in the "Year Book." The number ofundertakings included in the calculations is in each ease stated. It may be noted that the first amounts include only the authorized capital of limited liability companies. The second column records the amount of capital issued by such companies, together with the capital expenditure of private firms, and, in the case of companies largely interested in other forms of transport, an arnOunt proportionate to their interest in motor transport. Column 3 shows • the figure of . municipal capital actually borrowed or expended, and column 4 combines the figures of columns 2 and 3. Before passing to the important subject of dividends something may usefully be said as to the composition of the industry. In 1924-25, according to the definite information sin:Vied by 1,420 public transport undertakings, the number of vehicles in service was 21,557— private enterprise accounting for 20,546 and municipalities for 1,011. An approximate division of the total among the different classes of vehicles shows :—Buses 13,000, motor coaches 3,700, private-hire cars 1,400,, goods and parcels vehicles 3,400. As we have already seen, the number of companies engaged in the industry amounts to nearly 1,800—private firms 1,350 and municipalities 105. The bulk • of the traffic is handled by companies, the majority of which, in the joint stock sense, are "private companies." . Road transport, Unlike its rivals—railways and-tramways—has been, up to the present, essentially a business of small proprietorship. Statutory monopolies find no place in its history, and the corporate idea, in the sense Of large " public companies," has not been pursued to any great ex.tent. .

To-day the old order is changing, and if the future history of mechanical transport is to reproduce the features of other industries—as seems inevitable— this phase of development is destined to expand rapidly, accelerating with a growing recognition of the true aspect of public service. Already in many areas, by tacit understanding, combination, association or fusion of small owners, monopolistic tendencies are to be found. All this, with proper safeguards, is to the good and desirable if conditions of fierce competition are to be avoided, because no remuneration, commensurate with the value of tbe services rendered, can be looked for under such conditions.

We come now to the subject of dividends, but, for obvious reasons, calculations based on the operating results of all undertakings cannot be made. From such as are available, however, it is possible to arrive at figures of very definite value.

The statement in Table II shows the various rates of dividend or interest paid on capital last year, and the amount on which each rate was paid by 71 transport companies having an aggregate capital of £11,911,756.

These figures are based upon a preliminary survey and are subject to adjustment upon a final analysis of the returns for 1925, in respect of which year several companies have not yet declared dividends.

It is to be anticipated that these may somewhat affect the final result_ The figures in Table In show how these returns compare with previous years.

In conclusion, it may be of interest to compare the returns with those of electric traction undertakings, taking, for the purpose of comparison, the year 1924. The returns of 109 electric-traction companies for this year as recorded in " Garcke's Manual of Electrical Undertakings" are as follow :—Ordinary capital 3.71 per cent., preference capital 4.17 per cent., loan and debenture capital 4.54 per cent.—total average on an aggregate capital of £171,755,510, 4.18 per cent.