OPINIONS FROM OTHERS.

Page 20

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

The. Editor invites correspondence on all subjects c.onnecied with the use of conimercial motors. Letters -should .be on one side of the paper only and typewritten by preference. The right of abbreviation is reserved, and no responsibility for views expressed is accepted.

SteamVehicle Developments.

The Editor, THE COMMERCIAL MOTOR.

[1,718] Sir,—In reply to Mr. Clarkson's letter in your issue of February 24th, my quotations from Professor Osborne Reynolds aaid Professor Perry were given to substantiate my argument that efficient circulation in a steam boiler is a vital necessity. I fail to see how Mr. Clarkson can construe my quotations into • opinions by them as to the merits of the Clarkson thimble tube boiler.

With regard to Field tubes, the. provision of the inner tube gives a definite circulation of the water, which I contend is not obtained with Mr. Clarkson's thimble tubes.

The difference between the vertical position and the horizontal position of a closed tube without the inner tube is only a question of degree, and not one of prin. ciple ;' so also is the proportion of length to diameter and the tapering of the tube. In both eases the water has to get in and out of the tube and, unless the currents are properly guided, efficient circulation cannot be obtained.

In Mr. Clarkson's description of the action of the horizontal "thimble" tubes, he says that, previous to boiling point, the water divided itself into two strata, the lower stratum flowing into the tubes and the upper outwards, but when boiling point is reached the action alters. " of steam flowed upward from the lower stratum and formed the return .current in the upper stratum. This action proceeded until ebullition was slightly checked by the reduced volume of water, then the

• thimble tube was instantly refiltedwith water, and the generation of steam proceeded with practically no interruption."

In other Words, the circulation stop e until the steam formed in the tube overcomes the resistance of the water, and expels itself. This stoppage of circulation when the water is boiling, which is the working condition of a boiler, proves' the inefficiency of this type of water tube. For, obviously, the water cannot get freely to the heating surface.

This action is exactly the same• as that which takes place in a, vertical thimble tube. In this case, previous to boiling point., the hot water rises round the sides of the tube, flows towards the centre, and thence downwards. When boiling point is reached the upward currents interfere with the downward -currents, and ebullition occurs. Mr. Clarkson calls this action " pulsating circulation" ; but, as pointed out, there is a vast difference between ebullition and circulation. The introduction of the inner tube as in the Field tube, causes the upwaad currents to be separated from the downward currents, and enables the water to circulate freely after boiling point is reached.

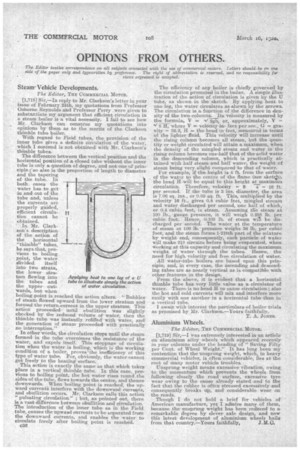

Applying heat to one leg of a U tube to illustrate simply the action of water circulation. The efficiency of any boiler is chiefly governed by the circulation promoted in the boiler. A simple illutration of the action of circulation is given by the U tube., as shown in the sketch. By applying heat to one leg, the water circulates as shown by the arrows. The circulation is a function of the difference in density of the two columns. Its velocity is measured by the formula, V = 2gh, or, approximately, V = "V 8.13, where V = velocity in. feet per sec. = gra vity = 32.2, II = the head in feet, measured in terms of the lighter fluid. This velocity will increase until the rising column .becomes all steam, but the quantity or weight oirculated will attain a maximum, when. the density of the mingledsteam and water in the rising column becomes one-half that of the solid water in the descending column, which is practically attained with half steam and half water, the weight of steam being very slight compared to that of water. For example, if the height is 4 ft. from the serface of the water to the centre of the flame (see sketch), the head H -will be equal to this height at maximum

circulation. Therefore, velocity = 8 4 = 16 ft. per second. If the tube is 3 ins. diameter: the area is 7.0E sq.. ins., or 0.05 sq. ft. This, multiplied by the velocity 16 ft., gives 0.8 cubic feet, mingled stream and water discharged per second, one half of which, or 0.4 cubic feet, is steam. Assuming the steam at 100 lb., gauge pressure, it. will weigh 0.258 lb. per cubic foot. Hence, 0.103 lb. of steam will be discharged per second. The water at the temperature of steam at 100 lb.' pressure weighs 56 lb. per eubie foot, and the steam forms 1-218th part of the mixture by weight and, consequently, each particle of water will make 218 circuits before being evaporated, when working at this capacity and circulating the maximum weight of water through the tubes. Hence,, the need for high velocity and free circulation of water.

All water-tube boilers are based upon this principle, and, in every case, the ascending and descending tubes are as nearly vertical as is compatible with other features in the design. • From the above, it is evident that a horizontal thimble tube has very little value as a circulator of water. There is no head H to cause circulation ; also the hot and cold currents will mix and interfere more easily with one another in a horizontal tube than ia a vertical tube.

I await with interest the particulars of boiler trials as promised by Mr. Clarkson.—Yours faithfully, T. A. IONE%

Aluminium Wheels.

, The Editor, THE COMMERCIAL MOTOR.

[1,719] Sir,—I was extremely interested in an article on aluminium alloy wheels which appeared recently in your columns under the heading of "Saving Fifty per Cent. of Wheel Weight" It has long been my contention that the unsprung weight, which, in heavy commercial vehicles, is often. considerable, lies at the root of many motor vehicle troubles. Unsprung weight means excessive vibration, owing to the momentum which prevents the wheels from following closely the road surface' excessive tyre wear owing to the cause already stated and to the fact that the rubber is often stressed excessively and consequently breaks up, and considerable wear on the roads.

Though I do not hold a brief for vehicles of American manufacture, yet I admire many of them, because the unsprung weight has been reduced to a. remarkable degree by clever axle design, and now this Latest development of aluminium wheels hails

from that country.—Yours faithfully, J. M.O.