Freeway lesson for GLC?

Page 42

Page 43

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

In the States motorways have provided opportunities to establish new bus routes to city centres

Report by Derek Moses

WHILE TOTAL public transport riding in the United States was trending downwards, buses employed on freeway and expressway routes showed small gains in passengers, some of whom previously went to work by car. Now, with total patronage levelling out, some motorway routes were increasing their revenues and traffic volumes, said Professor W. S. Homburger, University of California, on Wednesday, Prof Homburger, who is visiting lecturer, University of Salford, was addressing the Third Seminar on the subject of Operational Research in the Bus industry, being held at the University of Leeds this week. His subject was "Bus routes on urban motorways" —a topical one in view of the GLC's motorway box proposals. Urban motorways had been built in all metropolitan areas of the USA in the past 20 years, he said. Generally, radial motorways had been built first, penetrating to partial or complete motorway rings around the central business district (cbd). Tangential routes and outer rings followed later, or were still to come.

Suburban areas In outer suburban areas the motorways sometimes were located on the right of way of the original highway, thus obliterating it; parallel frontage roads were then built to provide access to smaller local streets and abutting property, but were not designed to handle through traffic, such as buses previously using the old road. It was in these circumstances that the first use of motorways by buses was compelled on operators by the highway builders. The delays to buses forced to leave the motorway at interchanges, to set down or pick up passengers, and then find their way back to the motorway led to the development by the engineers of special roadways and platforms within the motorway right of way.

In the central cities, where trip lengths were smaller and route coverage more dense, the motorways gave opportunities for the establishment of new bus routes, as opposed to rerouted old ones. This was feasible if the motorway was located in a corridor of heavy public transport movements for at least two or three miles, and there was sufficient demand for direct linking with the cbd which would fill several buses during the peak period.

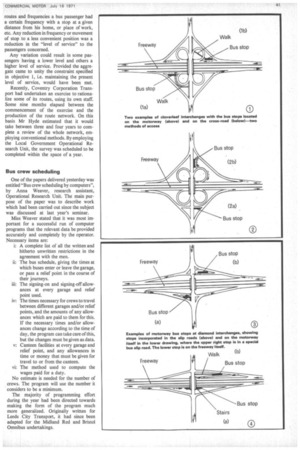

Bus stop sites Because of the faster journey times, there had been a favourable public response and operators had benefited from better utilization of vehicles and crews. If bus stops were needed—in the outer suburban areas for example—they could be either within the motorway or at the cross street at an interchange.

The latter was preferred if it did not cause undue delays to buses, said Prof Homburger, because passengers would have less walking distances to the stop. Where diamond-type interchanges were used, conditions were usually suited to the latter; however, it might be desirable to offer buses right of way when entering the cross street by specially actuated signal installations.

Where interchanges were of the cloverleaf type or any of the complex patterns which did not readily allow a bus to leave and reenter the motorway, the stop .had to be installed at the same level as the motorway. A special roadway with adequate acceleration and deceleration length was required, and a loading platform connected to the cross street by stairs (Prof Homburger claimed that escalators did not seem to be justified at present). The bus roadway should be connected to slip roads rather than the main motorway lanes.

Usual stops At the downtown end of the trip, the common practice was to route the buses into the regular street system where they made the usual stops and offered good coverage of the area. Off-street terminals, with their disadvantage of single-point coverage instead of area coverage, had been built in New York City because of the enormous volumes of buses, and in San Francisco, where the availability of an abandoned railway station and access roads had been utilized.

In conclusion, Prof Homburger said that considerable study was now underway to determine the feasibility of giving buses priority in entering motorways via special lanes on slip roads, or even exclusive slip roads. Coupled with metering schemes to keep motorway traffic flow always below the congestion level, this could assure fairly reliable performance of buses on motorways.

Evaluating bus network Earlier on the same day, a paper entitled "Designing and evaluating a bus route network" was presented by Mr. D. L. Hyde, general manager, Coventry Corporation Transport. He referred to a common allegation that many operators continued to provide services that followed the• old tram routes, adding that it was probably substantially correct. This was partly due to a feeling that in most cases the demand still existed, but mainly due to the absence until recent years of any satisfactory techniques for establishing current needs, Mr Hyde said.

In the past housing development took place along the old tram routes and early bus routes, and that was where people continued to live; consequently some bus routes did have a historical basis. The question facing Coventry's city council was whether the present system of routes and frequencies best met the needs of the travelling public. To try to resolve the matter it had been decided to retain the services of the Local Government Operational Research Unit. (The method employed was briefly described by Mr K. C. Rogers, LGORU.) Three objectives had been laid down by the city council, Mr Hyde continued. The LGORU was to investigate: 1: Present level of service at minimum cost.

To examine the existing pattern of routes and frequencies to see if the present level of service could be achieved at less cost.

2: Improved level of service for present expenditure.

To see if a better service than that at present being offered could be achieved for the current level of expenditure.

3: Maximum reduction in expenditurefor minimum reduction in level of service. In the event of economies being possible, to determine the areas in which the greatest cost savings could be achieved (ie service reductions and rationalization) at the minimum inconvenience to the public. From this it would follow that an endeavour would be made to establish a service where the maximum income in the form of revenue would be obtained for the least possible expenditure.

In view of the objectives it was important to clarify the meaning of "level of service", said Mr Hyde. With the present system of routes and frequencies a bus passenger had a certain frequency with a stop at a given distance from his home, or place of work, etc. Any reduction in frequency or movement of stop to a less convenient position was a reduction in the "level of service" to the passengers concerned.

Any variation could result in some passengers having a lower level and others a higher level of service. Provided the aggregate came to unity the constraint specified in objective 1, i.e. maintaining the present level of service, would have been met.

Recently, Coventry Corporation Transport had undertaken an exercise to rationalize some of its routes, using its own staff. Some nine months elapsed between the commencement of the exercise and the production of the route network. On this basis Mr Hyde estimated that it would take between three and four years to complete a review of the whole network, employing conventional methods. By employing the Local Government Operational Research Unit, the survey was scheduled to be completed within the space of a year.

Bus crew scheduling One of the papers delivered yesterday was entitled "Bus crew scheduling by computers", by Anna Weaver, research assistant, Operational Research Unit. The main purpose of the paper was to describe work which had been carried out since the subject was discussed at last year's seminar.

Miss Weaver stated that it was most important for a successful run of computer programs that the relevant data be provided accurately and completely by the operator. Necessary items are: i: A complete list of all the written and hitherto unwritten restrictions in the agreement with the men.

ii: The bus schedule, giving the times at which buses enter or leave the garage, or pass a relief point in the course of their journeys.

iii: The signing-on and signing-off allowances at every garage and relief point used.

iv: The times necessary for crews to travel between different garages and/or relief points, and the amounts of any allowances which are paid to them for this. If the necessary times and/or allowances change according to the time of day, the program can take care of this, but the changes must be given as data.

v: Canteen facilities at every garage and relief point, and any allowances in time or money that must be given for travel to or from the canteen.

vi: The method used to compute the wages paid for a duty.

No estimate is needed for the number of crews. The program will use the number it considers to be a minimum.

The majority of programming effort during the year had been directed towards making the form of the program much more generalized. Originally written for Leeds City Transport, it had since been adapted for the Midland Red and Bristol Omnibus undertakings.