SCOTS GLORY

Page 62

Page 63

Page 64

Page 65

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

Dominic Perry visits Islay where single malts bring profit as well as pleasure to the island's haulier

As you drive into the otherwise picturesque town of Port Ellen on the Hebridean island of Islay your view is dominated by a number of large grey silos. These tall,corrugated cylinders tower over pretty much everything else in the town and as I drive past at just before 9am one of Ben Mundell's trucks is already sitting under the silos picking up a load of barley.

Well, it's not barley exactly and the contents of the truck and silos give a clue as to the economics of this part of Scotland.The buildings in question and the more photogenic whitewashed warehouses next door all belong to global drinks giant Diageo (formerly Guinness, formerly United Distillers and so on) and are its Port Ellen mailings.

This is where ordinary barley is roasted and milled for use in Islay's most famous and largest industry — whisky distilling. Seven different distilleries are dotted around Islay, plus one on nearby Jura, producing both revered single malts and spirit for use in blending. Given that almost all the raw material for the distilleries has to be delivered onto the island and just about all the end product has to leave, the industry provides a relatively lucrative living for Ben Mundell's fleet.Although its headquarters are across the water on the Scottish mainland at Tarbert, Mundell also has a sizeable presence on Islay.

In fact, his trucks get everywhere (not least at Islay's airport where a child's crayon drawing of one hangs among pictures of cows and sheep) later in the day I'm sat at Diageo's Caol Ha distillery overlooking the Sound of Islay with Jura gleaming greenly in the background. when the noise of a diesel engine growls across the relative tranquillity of the scene. It's another of Mundell's trucks, this time coupled to what appears to be a regular curtainsided trailer. However, appearances are deceptive — behind the curtains there is a 15,000-litre tank which takes several hours to fill with spirit newly distilled at the plant.The driver climbs out, attaches the relevant hose from the distillery and then decouples the tractor before heading off He'll be back later in the day to pick up the spirit-laden trailer before it's put on the evening boat from the island. In fact, each day the Caol Ila distillery sends 15,000 litres of spirit off to Stirling in Scotland's central belt where it is matured until ready for drinking.

Spirit for blending

Caol Ila's production is mostly geared towards making spirit for blending — combining with other whiskies to produce brands like Johnnie Walker. As a general rule, around 10% of any distillery's production goes towards blending. To skirt round the more technical aspects of whisky making, the basic premise is that malted barley goes in, is fermented and then the resulting liquid is distilled,leaving you with raw spirit and a product known as draft— the post-fermentation remains of the malted barley that is sold on for use as animal feed. So if like Ben Mundell, you are a haulier involved in this industry then it's likely that your trucks will be kept busy.A look at the schedules for Mundell's fleet on the day I visit are illustration enough of the complex movements involved: driver Alan McPhee starts at the yard, heads to Port Ellen to pick up building materials, returns to base, then is off to Port Ellen makings for a load of malt to Jura and a trailer full of draft back, before finishing with another load of malt to Bowmore distillery.

Another driver,Alistair McDonald, has an Sam start at Lagavulin hauling a trailer of whisky. He then takes two trailers to Laphroaig, followed by a load of whisky from Ardbeg, finishing with two loads of malt from Port Ellen to Laphroaig and Lagavulin distilleries before catching the evening ferry to the mainland. Mundell's trucks are frequent visitors to the Port Ellen makings — around half of the island's malt comes from this site, the rest from maltsters on the mainland. Either way it's Mundell's vehicles that do the eventual delivery to the stills. Equally inevitably it's B Mundell trucks that cart the draff off at the end of the process as well, although this can be anything but a local exercise. "We try to give farmers on Islay the first shot,but if there's any left over it goes to the mainland, as far away as Dumfriesshire if needs be," he explains.

Ro-ro ferries

The firm started just after the Second World War, becoming limited in 1971, and was initially confined to the mainland before the introduction of ro-ro ferries which allowed it to expand to serve the Islay distilleries. Drivers are based in both Tarbert and at the firm's island base not far from Port Askaig,with trailers shuttling between the two to save space and money on the ferry crossings.

It's these that prove one of the biggest bugbears of Mundell's working life, particularly the crossing to Jura: "The ferry is frequently off thanks to bad weather. In January this year we had two trucks stuck over there for four days.

"You can get the driver back and possibly the unit back,but the problem is the loaded trailer," he adds.As well as the fickle Scottish climate playing havoc with the sailings, there is the ulcer-inducing issue of price as well. "The ferry is the killer, it's ridiculously expensive," as Mundell notes acidly.There has been the suggestion of running a dedicated freight service but there isn't the capacity,he says."Even with all the commercial freight going to Islay you couldn't do it.

"The only way to make it profitable would be to run a roving ferry down the coast and all the time you'd be competing against a company that is generously subsidised."

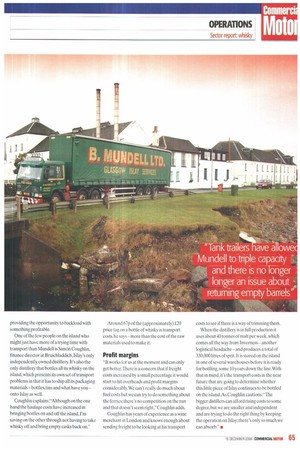

With prices calculated on vehicle length rather than weight,it's clearly vital "if humanly possible" to maximise loaded running, or the truck doesn't pay its way.This is in part what prompted the purchase of its tank curtainsiders previously, spirit coming off the island was transported in barrels, with around 80 to a load.

The tank trailers have allowed Mundell to triple capacity and there is no longer an issue of having to bring the empty barrels back, providing the opportunity to backload with something profitable.

One of the few people on the island who might just have more of a trying time with transport than Mundell is Simon Coughlin, finance director at Bruichladdich, Islay's only independently owned distillery. It's also the only distillery that bottles all its whisky on the island, which presents its own set of transport problems in that it has to ship all its packaging materials bottles, tins and what have you onto Islay as well.

Coughlin explains: 'Although on the one hand the haulage costs have increased in bringing bottles on and off the island. I'm saving on the other through not having to take whisky off and bring empty casks back on." Around 67p of the (approximately) f20 price tag on a bottle of whisky is transport costs, he says -more than the cost of the raw materials used to make it.

Profit margins -It works for us at the moment and can only get better.There is a concern that if freight costs increased by a small percentage it would start to hit overheads and profit margins considerably. We can't really do much about fuel costs but we can try to do something about the ferries; there's no competition on the run and that doesn't seem right" Coughlin adds.

Coughlin has years of experience as a wine merchant in London and knows enough about sending freight to be looking at his transport costs to see if there is a way of trimming them.

When the distillery is in full production it uses about 40 tonnes of malt per week, which comes all the way from Inverness another logistical headache -and produces a total of 330,000 litres of sprit. It is stored on the island in one of several warehouses before it is ready for bottling, some 10 years down the line. With that in tnind,it's the transport costs in the near future that are going to determine whether this little piece of Islay continues to be bottled on the island.As Coughlin cautions:"The bigger distillers can afford rising costs to some degree, but we are smaller and independent and are trying to do the right thing by keeping the operation on Islay,there's only so much we can absorb." •