Packaging for Road Transport

Page 52

Page 53

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

By a Special Correspondent

GOODS transport operators are well used to tackling with complete success many difficult haulage problems. The routine risks of breakage have progressively been reduced by suspension improvements and better road surfaces. Many of the larger contractors under

take their own packing. There still remain, however, marginal consignments about which even the most experienced contractor may entertain doubts. And there is the undoubted fact that loads are tending to become more and more expensive, and more delicate.

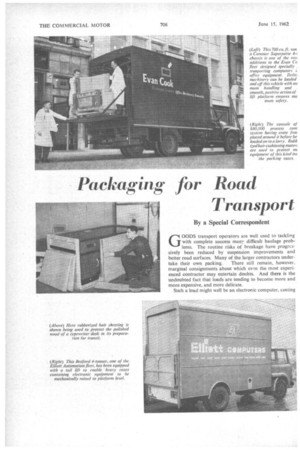

Such a load might well be an electronic computer, costing in the region of £100,000; delicate components here present a considerable problem to the haulier. He Might have no doubts about delivering it in one piece, but naturally might well have mental reservations about the effect of road shocks on sensitive units of the assembly. .

Today, such doubts can be resolved by packaging designers, who take into account such hazards as uneven road surfaces, so-called " level " crossings, sudden braking, and the possible shocks sustained in handling. Certainly, a valuable load like a computer should be adequately provided with a stout outer case and elaborate cushioning device's to hold it firm and protect its more delicate components.

These developments in packaging are the outcome of special study, which has emerged almost as an exact science. It might not, in fact, be overstating the matter to suggest that the specialist can sometimes teach the operator something of value. Awareness of the problems involved has led to the widespread use of cushioning materials such as rubberized hair and latex foam.

In the first place, consideration should be given to the risks to the load inherent in transport by road. These include: accidental dropping during loading; vibration and exceptional buffeting due to road surface variations; and crushing, due to the accidental moving of other loads on the vehicle. The fragility of the individual load has also to be accurately assessed.

One example is delicate instruments, all of which must be regarded as fragile. The individual degree of fragility has to be determined exactly, in order that the type and amount of protective packaging can be ascertained. The working unit upon which packaging experts base their calculations is known as the fragility factor, expressed as a multiple of the force of gravitation which a load can sustain without damage to, or dislocation of, its components. An illustration of the effect of a drop in terms of gthe gravity pull of the earth--would be furnished by a paperweight on a table top. At rest, it would be subjected to a force of 1 g (its own weight); if dropped, however, from a height of 1 ft., it might be subjected to many hundreds of g. But superimposing a resilient cushion on the desk, say 1 in. thick, would limit the deceleration to about 30 g; a 2-in. cushion 15 g; and so on, pro rata.

The fragility factor can be scientifically assessed by an instrument known as a retarded drop table. The equipment, or part of the equipment likely to be the most vulnerable to shock, is subjected to drop tests equivalent to progressive "deceleration levels" of 5 g, until some small shock effect becomes discernible. The exact g multiple is thus ascertained. The degree of fragility has to be matched by an equally accurate knowledge of the protective characteristics of various materials.

A typical specialist packaging design company is Hairlok Laboratories, Ltd., Chiswick, London. The results of hundreds of static and dynamic tests have been embodied , into graphs which enable pack designers to prepare their specifications on a theoretical basis. In practice, however, a full-scale replica of the load is often made; exhaustive trials are then carried out on a dummy rig simulating the shocks likely to be encountered in transit by road.

Under normal conditions, packages are subject to shocks at a rate governed by the speed of the vehicle and the quality of the road-surface-usually in the range of 2-4 c.p.s. Amplitude of the bumping motion is up to 1 in., and the package may be subjected to acceleration levels ranging between 5.g and 40 g. Facilities are available for simulating these conditions with a maximum load of 500 lb:

Among items that can present special problems and which operators should have care are electronic instruments and apparatus, electrical and mechanical equipment including generators, motors, transformers and switchgear, and various machine tools with brittle castings or other vulnerable parts.