Rescuing

Page 56

Page 57

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

ROMANIA

• Steve Sims is Paul Selway Transport's Eastern Europe expert; the past couple of years he has been driving for the Taunton-based company on trips of up to three weeks to Yugoslavia, Czechoslovakia, East Germany and Hungary, where expanding trade links with the West offer rich pickings to imaginative hauliers.

As a result, he is no stranger to the had roads, the bribes that speed things up at some border ports, and the endless stream of kids who plead with western truck drivers for chocolate, chewing gum and Coca-Cola.

When Sims' boss Paul Selway saw a news report on Boxing Day about conditions in Romania following the overthrow of dictator Nicolai Caecescu, he decided to collect supplies from around the country in response to an appeal from a charity: Sims volunteered to take them in his truck to Romania without wages. His was the only UK wagon in a convoy of eight 11G Vs organised by the Munich-based charity Project Direct Four to Romania. The group's aim is to bring selective short-term relief to the people, helping them to rebuild their economy rather than growing dependent on aid. Part of the task is ensuring that the medicines and specially-prepared food packages, which can keep a family alive for three months, do not fall into the wrong hands, says the charity's leader Erich Frisch. If blackrnarketeers get a hold of them, they resell them at a profit.

Romania is in a mess. Unlike other Eastern European countries, where reformers have replaced old-guard communists and are steering the economies to a freer market, Romania is on the brink of civil war and economic collapse. Brought to its knees by Caecescu, the country's committee of national salvation has the almost impossible task of bringing order to chaos.

Remnants of the dictator's former secret police, the now-outlawed Securitate, still wander free and the new provisional government has been tainted by allegations that it is run by former henchmen of Caecescu who have conveniently changed their political spots.

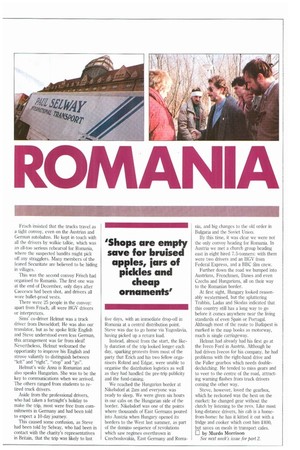

Driving around the country, it is difficult to see how even immediate political stability or democracy could save its shattered economy. Shops are empty save for bruised apples, jars of pickles and cheap ornaments. Once the breadbasket of Europe, Romania's agricultural base has been demolished by Caecescu in a misguided bid to force peasants into collective state farms and create heavy industry.

Certainly the people are freer. Although the elation that followed the capture and execution of the Caecescus is over, newspapers are published by political parties and 10-year-olds scribble "Democracy" and "Liberty" in the road grime on truck tailgates alongside the names of heavy metal bands like Kiss and Slayer. Weeks ago, such an act could have got them shot; today, the 17-year-old conscript soldiers just shrug and walk by.

Sims met up with the convoy in Munich two weeks ago. He had travelled there from England after collecting donations of food, clothes and medicines. Four other Paul Selway trucks were involved: their loads were sent free to Germany by Sealink and Norfolk Line, which donated three trailers.

In Munich, the charity had found a warehouse and recruited 100 locals to pack everything into boxes. Other trucks had been donated by MAN, which is based in Munich, Mercedes and local haulage company Topstar, whose owner is a Romanian exile. Altogether, 90 tonnes of food and 60 tonnes of clothes and medicine were sent to Romania.

The convoy was set to go at lunchtime on Wednesday 31 January. It comprised four MAN rigids (two with drawbar trailers); two Mercedes drawbars from Topstar; Steve Sims' Iveco Ford 190.48 Turbostar; a Mercedes Unimog and a pair of lsuzu Troopers — one hitched to a kitchen trailer. Diesel was provided free by a local fuel company. The customs clearance depot in Munich issued papers and seals which the organisers hoped would cut delays at borders to a minimum. It was there that we hit our first hitch: one of the MAN drawbar rigs had trouble with its gearbox. Its trailer was hooked to one of the other MANs and its drivers were left to limp their truck to the workshop and catch up at the Austrian border.

The drive to the crossing, near Salzburg, took three hours; it took about as long again to pass through what is one of the most notoriously slow, and bureacratic borders in Western Europe. Eventually the authorities agreed to put the seven trucks' loads — together with the late arrival — on the one set of custom papers. As a charity we also got dispensation to break Austria's night lorry ban. Frisch insisted that the trucks travel as a tight convoy, even on the Austrian and German autobahns. He kept in touch with all the drivers by walkie talkie, which was an all-too serious rehearsal for Romania, where the suspected bandits might pick off any stragglers. Many members of the feared Securitate are believed to be hiding in villages.

This was the second convoy Frisch had organised to Romania. The first one was at the end of December, only days after Caecescu had been shot, and drivers all wore bullet-proof vests.

There were 25 people in the convoy: apart from Frisch, all were HGV drivers or interpreters.

Sims' co-driver Helmut was a truck driver from Dusseldorf; He was also our translator, but as he spoke little English and Steve understood even less German, this arrangement was far from ideal! Nevertheless, Helmut welcomed the opportunity to improve his English and strove valiantly to distinguish between "left" and "right", "stop" and "go".

Helmut's wife Anna is Romanian and also speaks Hungarian. She was to be the key to communications when we arrived. The others ranged from students to retired truck drivers.

Aside from the professional drivers, who had taken a fortnight's holiday to make the trip, most were free from commitments in Germany and had been told to expect a 10-day journey.

This caused some confusion, as Steve had been told by Selway, who had been in contact with the charity's representatives in Britain, that the trip was likely to last five days, with an immediate drop-off in Romania at a central distribution point. Steve was due to go home via Yugoslavia, having picked up a return load.

Instead, almost from the start, the likely duration of the trip looked longer each day, sparking protests from most of the party that Erich and his two fellow organisers Roland and Edgar, were unable to organise the distribution logistics as well as they had handled the pre-trip publicity and the fund-raising.

We reached the Hungarian border at Nikelsdorf at 2am and everyone was ready to sleep. We were given six hours in our cabs on the Hungarian side of the border. Nikelsdorf was one of the points where thousands of East Germans poured into Austria when Hungary opened its borders to the West last summer, as part of the domino sequence of revolutions which saw regimes overthrown in Czechoslovakia, East Germany and Roma

nia, and big changes to the old order in Bulgaria and the Soviet Union.

By this time, it was clear we were not the only convoy heading for Romania. In Austria we met a church group heading east in eight hired 7.5-tonners: with them were two drivers and an HGV from Federal Express, and a BBC film crew.

Further down the road we bumped into Austrians, Frenchmen, Danes and even Czechs and Hungarians, all on their way to the Romanian border.

At first sight, Hungary looked reasonably westernised, but the spluttering Trabbis, Laths and Skodas indicated that this country still has a long way to go before it comes anywhere near the living standards of even Spain or Portugal. Although most of the route to Budapest is marked in the map books as motorway, much is single carriageway.

Helmut had already had his first go at the Iveco Ford in Austria. Although he had driven lvecos for his company, he had problems with the right-hand drive and the Fuller gearbox which needs doubledeclutching. He tended to miss gears and to veer to the centre of the road, attracting warning flashes from truck drivers coming the other way.

Steve, however, loved the gearbox, which he reckoned was the best on the market: he changed gear without the clutch by listening to the revs. Like most long-distance drivers, his cab is a homefrom-home: he has it kitted it out with a fridge and cooker which cost him £400, but saves on meals in transport cafes. 0 by Murdo Morrison