MERCEDES-BENZ SPRINTER 416

Page 28

Page 29

Page 30

Page 32

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

I

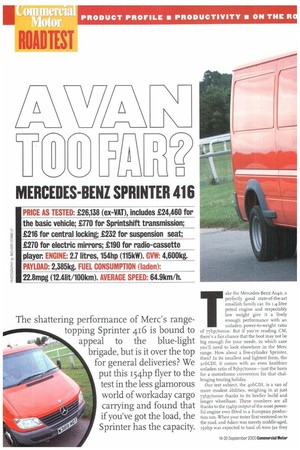

PRICE AS TESTED: £26,138 (ex-VAT), includes £24,460 for , the basic vehicle; STIO for Sprintshift transmission; i 1216 for central locking; £232 for suspension seat; i £270 for electric mirrors; £190 for radio-cassette cl player. ENGINE: 22 litres, 154hp (115kW). GVW: 4,600kg. 1 PAYLOAD: 2,385kg. FUEL CONSUMPTION (laden): :0 22.8mpg (12.41it/100km). AVERAGE SPEED: 64.9km/h1

The shattering performance of Merc's rangetopping Sprinter 416 is bound to appeal to the blue-light brigade, but is it over the top for general deliveries? We put this 154hp flyer to the test in the less glamorous world of workaday cargo carrying and found that if you've got the load, the Sprinter has the capacity.

Take the Mercedes-Benz Aujo, a perfectly good state-of-the-art smallish family car. Its 1.4-litre petrol engine and respectably low weight give it a lively enough performance with an unladen power-to-weight ratio of 77hp/tonne. But if you're reading CM, there's a fair chance that the boot may not be big enough for your needs, in which case you'll need to look elsewhere in the Merc range. How about a five-cylinder Sprinter, then? In its smallest and lightest form, the 216CD1, it comes with an even healthier unladen ratio of 85hp/tonne—just the basis for a motorhome conversion for that challenging touring holiday.

Our test subject, the 416CD1, is a van of more modest abilities, weighing in at just 73hp/tonne thanks to its beefier build and longer wheelbase. These numbers are all thanks to the 154hp output of the most powerful engine ever fitted to a European production van. When your tester first ventured on to the road, and Adam was merely middle-aged, i5ohp was expected to haul 16 tons (as they were then) and even today, it's the benchmark figure for the 7.5-tonne category.

PRODUCT PROFILE

When the new Sprinter was launched earlier this year, the visual changes were subtle, to say the least. The most obvious identifier is the larger three-pointed star badge on the front, accommodated by a cut-out in the lower edge of the bonnet. Virtually all of the changes consisted of the new engines and transmissions under that bonnet, and in the redesigned cockpit.

We tested a lesser Sprinter, a long wheelbase 313G DI, just a few months ago (CM r-7 June) so we will just recap briefly. Besides the usual chassis-cab and mini-bus variants, vans are available with four GVWs, three wheelbases and two roof heights. They're propelled by a quartet of new common-rail turbodiesels; all but the lowest-powered one have variable geometry turbochargers. They are three 2,15rcc four-cylinders rated at 8o, 107 and 127hp, and the 2,686cc five-pot tested here. The five produces 154hp at 3,800rpm with 330 Mm of torque at1,400-2,400rpm. As if that torque plateau was not impressive enough, at least 90% of that torque is on tap from 1,200rpm right up to 3,150rpm.

As well as the monster engine, our 4.6tonne GVW test van features Mercedes' automated six-speed Sprintshift transmission. With the shorter (3,550mm) of the 4r6CDI's two wheelbase options and the standard roof height, the Sprinter was refreshingly free from the frills and fripperies that often accompany press test vehicles. Its only indulgence was the rather lurid tangerine paintwork which meant that no-one could fail to see it as it approached.

Twin rear wheels, which are fitted with 195/701215 tyres rather than the 225-section items of the 3,5-tonner, are standard on this model, and are covered by plastic flared wheelarches with a thoughtful lead-in ramp to stop them being ripped off in tight spots.

PRODUCTIVITY

One thought recurred throughout this test: no-one is likely to buy a 416 unless they really need the power and the payload. The price alone, exactly L4,000 more than an identically specced 313, will ensure that, even if the obligatory tachograph doesn't, Model for model, the 4.6-tonner gives 940kg of extra payload compared with the 3.5tonne versions; the remaining I6okg is accounted for by the twin rear wheels and beefier suspension. To put its capacity into perspective, its net payload of 2,385kg is rather more than a fully freighted Citroen Dispatch.

Given its appetite for hard work, we weren't expecting the Sprinter 416 to defeat the laws of physics and win any economy awards—the price of the extra tonne of payload is a laden figure of 22.8mpg, just a tenth of an mpg better than the 129hp VW LT46. Running unladen, however, the penalty diminishes; its 28.3mpg puts it within easy reach of the 3.5tonne benchmark. There is absolutely no indication that the Sprintshift transmission has any detrimental effect on fuel economy, behaving as it does in the same manner as any reasonably competent driver.

Beyond a certain threshold of power, average speeds are becoming academic as we are

0 increasingly restrained only by speed limits. This is perfectly illustrated in the Sprinter's case—slight differences in traffic signal stops and the like meant that the laden run was completed a minute quicker than the unladen. Suffice it to say that if the 416 isn't fast enough for you, then you must have some fairly unusual requirements.

The unglazed rear doors have stops at 90 and 18o°. However, the lack of a positive detent in the open position proved irritating, particularly while loading on a windy day as the upwind door kept blowing shut. There was no such problem with the side door; its strong catch held firm even on steep slopes. The load floor is 7romm from the ground, which is reasonable for a rear-wheel-driver, and has a phenolic resin ply covering as standard. Also standard are the eight hefty tiedown rings, but the ply-lined loadspace walls were a dealer-fitted extra.

ON THE ROAD

This is definitely a van that likes to work, and is one of those rare beasts that performs better the more it's loaded. In truth, the prodigious amount of torque is a liability when running unladen. Under hard acceleration the traction control, which now works by reducing engine power instead of applying braking effort to the spinning wheel, can result in rather jerky progress, and roundabouts and junctions need considerable respect.

Load it to its maximum, though, and it's a different story. The engine gets enough to do to stop it feeling like a Formula i car negotiating Hyde Park Corner, while the suspension also gets compressed enough for it to work properly. Even on damp, greasy roundabouts the traction control rarely gets disturbed.

Compared with the 12,7hp 3.5-tonner, the laden Sprinter 416 takes two seconds longer for the proving ground sprint to 50 mph, and loses about the same time during the 488okrn/h and 64-96km/h tests. Top speed is academic, but just in case your drivers feel the temptation to race reps' cars up the motorway, the makers have restricted it to the magic ton.

Our initial experiences with Sprintshift were a good test of its intuitiveness, as the van's handbook had gone missing. The system is controlled by a stubby lever on the dash which is an easy reach away from the wheel. The starting position, logically enough, is N, from where it nudges backwards into R and to the left for A. In normal use you just leave the lever in A (for automatic) mode—simply press the accelerator to go. The lack of a handbook only caused us one problem; if the engine was switched off before engaging neutral the electronics became confused, making it exceedingly difficult to find neutral at the next start-up.

From a standing start the first up-change feels rather ponderous but the change improves considerably the higher you get. In its 416 form the Sprinter benefits from a more leisurely, part-throttle driving style which gives smoother and earlier changes, keeping in the torque band and losing virtually no time, maybe even gaining some. Attempting to use full throttle in every gear is pointless as the Sprinter wants to gallop away.

Downshifts are hardly ever noticeable, except that when you need to kick down to accelerate away in a hurry, such as when nipping into traffic gaps, there is what seems like an interminable delay while the electronic brain decides what to do. Sprintshift's fine control during low speed manoeuvring, a weak point of some dutchless vans we've driven, proved to be perfectly satisfactory. It was seriously tested in a very tight situation reversing out of a drive with literally millimetres to spare, but once the transmission engages it can be controlled extremely precisely, both forwards and back.

If you require manual control simply move the lever backwards or forwards to change up or down. Any attempt to make a damaging out-of-parameter shift is not permitted. In manual mode Sprintshift will hold the selected gear until you decelerate, when it will find a suitable gear for moving away. However, the automatic mode works well enough that there is no real point in using manual, except for the extra engine braking it gives on severe descents. It isn't possible to hold the current automatically selected gear by changing to manual—the system will only allow entry to manual mode by changing up or down a gear. Hill starts are helped by the system holding brake pressure for one second after release of the pedal to prevent rolling back. When we finally got hold of a handbook we found that it should be possible to choose either first or second gear for starting off, but we didn't manage it.

Overall Sprintshift works extremely well, although this type of automated conventional transmission is never likely to become as smooth as a torque converter/epicyclic system. Maybe a little more on-board computing power could be used to improve the kickdown response.

The firm suspension needed to keep the 4.6-tonne gross weight off the road has an inevitable penalty when unladen, giving a firm but tolerably comfortable ride on all but the worst surfaces. With a full load in the back, the ride was fine. Besides the obvious benefits of load restraint and noise suppression given by a full bulkhead, a less obvious advantage is the extra rigidity given to the body. Our van, with no bulkhead, was already suffering from some creaking and rattling of the load compartment doors on rough surfaces. Spend the D8o--you won't regret it.

Despite the smaller amount of rubber on the road at the front of the 416, it didn't demonstrate any sign of the mild understeer apparent on the 313. The handling remained neutral in all weight conditions unless provoked by carelessly unleashed torque. Steering is excellent, with just the right amount of weight and accuracy The latest Sprinter still features the traditional, and once controversial, long brake pedal travel, but the braking action is as powerful and progressive as you would expect from a system which incorporates the very latest in ABS and electronic braking distribution technology. Less impressive was the poorly adjusted handbrake. It ran out of travel before providing enough effort to hold on the 25% (i-in-4) test hill, and was slightly awkward to reach requiring a noticeable drop of the driver's shoulder.

Manually adjusted mirrors give a decent field of view but, disappointingly for a new design, they have no dual-zone blind-spot facility. Visibility in every other respect is good.

CAB COMFORT

One big advantage the Sprinter enjoys over some competitors is the ease of access given by the doors, which open to a full go°. Once aboard the driver is cosseted in an excellent mechanically suspended seat with full adjustment, including height, recline, adjustable cushion length, pneumatic lumbar support and driver weight. All three occupants get three-point inertia belts, height adjustable on the outer positions. A sober light-grey fabric is used to trim the seats, while the roof is lined with Merc's traditional tweed-look material. There is plenty of painted metal on view on the tops of the door frames, an issue which varies in importance according to the body colour—ours was bright orange!

Space in the footwell was rather cramped for the right foot, even with our delicate daisies, so the standard-issue emergency service size 125 likely to be controlling the Sprinter 416 could have real problems.

The newly facelifted dashboard is thoroughly contemporary, as it should be. Its grey grained plastic finish has a softish feel, but an even softer soft-feel is available as an option. Housed in a cowled binnacle, the instrument panel is home to water temperature and fuel gauges, a 90-scale rev counter and an absolutely accurate i8o°-scale speedo. Although the speed is predominantly indicated in km/h, the mph reading on a smaller inner scale is easy to read once you get used to it. The digital odometer display includes a clock and the Sprintshift gear position indicator.

The attractive four-spoke steering wheel contains the horn push but no airbag (a 1168 option for the driver only or f961 for all occupants). The large hazard-light switch is mounted on top of the column shroud, where its use involves sticking an arm through the wheel, not always a good idea, while conventional column stalks have lights on the left and wipers on the right. A panel to the right of the column contains the headlamp leveller and rear foglight switch.

The central dashboard is arranged towerfashion, topped by a basic Mercedes-branded RDS radio/cassette player, just above the rotary controls for the four-speed heater (with recirculatory facility). Mercedes claims, and we couldn't possibly argue, that its new commonrail engines are so thermally efficient that there isn't enough wasted heat available to fully warm the cabin, so markets with cold climates, including the UK, get an auxiliary diesel-powered heater as standard. Four fresh-air vents are evenly spread across the fascia, with two more on top for the windscreen.

Continuing downwards, next to a useful document clip, we reach the secondary switch panel, which in this case houses the traction control override and two-way central locking button allowing front, rear or all doors to be locked as required. Below this is a pen-holder, then the Kienzle digital tachograph, and finally a combined receptacle for smokers and drinkers.

The driver's door carries electric window switches (back to front on this example with the passenger window switch on the right, and vice versa). The windows themselves are rather leisurely in operation, with no onetouch facility. Dual-compartment door bins are fitted to each door, as are dropdown pockets in the lower panels intended for the first aid kit and warning triangle which are compulsory in many markets. Tools and wheelchanging kit continue to hide beneath a false floor in the passenger footwell.

In front of the passenger is a deep tray and a good-sized lockable glove box with cup recesses, and there is a small under-seat box behind the centre occupant's shins. What looks like a length of drainpipe bolted behind the driving seat is actually a two-litre bottle holder, although with no bulkhead it is rather vulnerable. There are two large plain sun visors bereft of vanity mirrors and ticket holders, with their central gap shielded by a blacked-out area on the glass. A combined interior and map light lives over the screen, with two further lights in the load space.

SUMMARY

As well as presenting a second chance to appraise the new Sprinter, this test covers three new facets of the breed: the big engine, the automated transmission and the 4.6tonne chassis. Overall, the latest Sprinter is something of a puzzle. A basically intelligently designed package is prevented from being the perfect van by a few silly ergonomic oversights, such as the out-of-reach handbrake and the too-basic mirrors—but its dynamic abilities are above reproach.

If you plan to buy a 154hp Sprinter for some macho desire to be King of the Road, and no doubt some will, you deserve all you get. Either your licence will be at risk if you let it have its head, or your nerves will suffer from holding it back. Sprintshift does everything it says on the can, and is well worth its £7.7o cost if you spend any amount of time on the mean city streets. And of course, that top GVW gives a top payload if you can use it.

We received the Sprinter 416 wondering if 154hp was really necessary in a van, and the answer for most commercial operators is a resounding no. But, like Viagra, it's reassuring to know that it's there if you need it.

II by Cohn Barnett