A Daimler Tested Round the Clock

Page 42

Page 43

Page 44

Page 45

Page 46

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

By

L. J. Cotton, M.I.R.T.E.

and

P. A. C. Brockington, A.M.I.Mech.E.

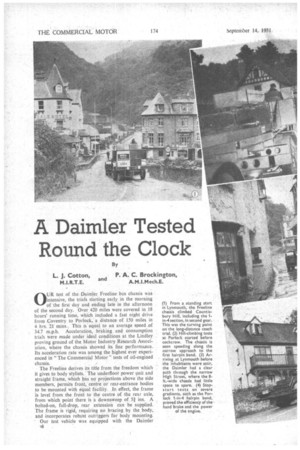

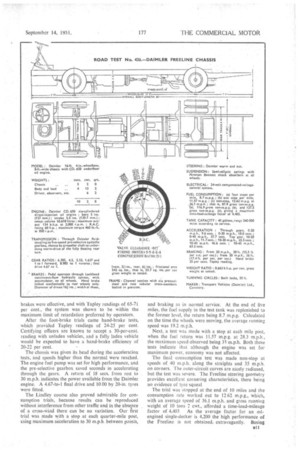

0 UR test of the Daimler Freeline bus chassis was intensive, the trials starting early in the morning of the first day and ending late in the afternoon of the second day. Over 420 miles were covered in 18 hours' running time, which included a fast night drive from Coventry to Porlock, a distance of 150 miles in 4 hrs. 21 mins.. This is equal to an average speed of 34.7 m.p.h. Acceleration, braking and consumption trials were made under ideal conditions at the Lindley proving ground of the Motor Industry Research Association, where the chassis showed its fine performance. Its acceleration rate was among the highest ever experienced in "The Commercial Motor" tests of oil-engined chassis.

The Freeline derives its title from the freedom which it gives to body stylists. The underfloor power unit and straight frame, which has no projections above the side members, permits front, centre or rear-entrance bodies to be mounted with equal facility. In effect, the frame is level from the front to the centre of the rear axle, from which point there is a downsweep of 51 ins. A bolted-on, full-drop, rear extension can be supplied. The frame is rigid, requiring no bracing by the body, and incorporates robust outriggers for body mounting. ' Our test vehicle was equipped with the Daimler

18 CD.650 10.6-litre direct-injection oil engine, arranged foi

horizontal mounting and -gover'ned 2,000 r.p.m. for maximum power (134 b.h p.) 'This unit is based on the vertical engine, but has a redesigned sump and reversed connecting rods to give upcvard splash. The water pump is alsd differently placed. Minor changes have been made to the carnshaft lubrication system, and the relief valve of the main oil supply discharges direct into the six-gallon sump. Other features include alarger intake manifold, with single pipe branches, a timingcase breather connected to the manifold, and a reshaped exhaust branch.

Apart from extensions on both sides for mounting purposes, the timing case is un altered. Installation details• of the Daimler engine include a V-shaped front mounting, with two Metalastik pads acting in shear interposed between a flanged bracket bolted to the underside of across-member, and a similar bracket attached to the front of the crankcase. The shear pads in the rear mounting are located between an inverted V-bracket, bolted to the rear face of a rear cross-member and the flanges of the timing-case cover. The timing gears are arranged at the flywheel end of the power unit. A tie rod fitted with Metalastik bushes limits fore-and-aft movement. The crankshaft centre line k located to the near side, and provides an approximately neutral transmission line with the gearbox and offset worm drive. Standard Daimler units are used in the transmission components, an open-circuit fluid coupling transmitting the drive to a five-speed, direct-drive-top, pre-selective, epicyclic gearbox, with manual linkage between the gear-engagement pedal and bus bar.

Unusual details of the Freeline chassis include centralpivot steering, phased suspension and special cooling arrangements, all of which were put to thorough test during the trials on Porlock. The steering drop-arm is linked to a central pivot mounted on the chassis, the lower pivot arm being horizontal and moving about the pivot connection in approximately the same plane as the axle. This arrangement provides kick-free steering under all road conditions, and improves the steering lock so much that the hairpin bends on Porlock could be negotiated in a single sweep without reversing.

Careful distribution of weight between the axles has made it possible to employ .5-ft. 2-in. springs at both front and rear to give phased suspension, and with the addition of Newton Bennett shock absorbers the chassis was notably free from cyclic pitching. Fast cornering during the night drive proved the chassis to be free from roll, the front shock absorbers being inclined at an angle to the vertical to increase roll resistance.

Although underfloor engines are noted for cool lubricating-oil temperatures, the water cooling sometimes presents a problem. In some chassis, the surface area of the tube stack is restricted when sandwiched between the frame members under the body floor, and with airflow obstructed by the front axle, more care is required in designing radiators than ever before.

With the Freeline, the radiator is behind the axle and. below the floor, but it has a contra-flow tube stack, Clayton Dewandre tubes and a 21-in.-diameter fivebladed fan of closed-coWled axial-flow pattern, with aerofoil fan sections. Cooling efficiency was put to thorough test at Porlock, but the results showed an ample margin for operation in the tropics.

Attached to the rear, of the fan spider is a Lockheed Mark V hydraulic pump for the continuous-flow braking system, which incorporates an accumulator cylinder below the pedal. Tests made with a stalled engine revealed that 12-14 useful brake applications could be made before the accumulator required recharging.

Our test chassis was loaded to 94 tons gross in readiness for the 'trials, and with thee hefty observers occupying the " engineers " cabin, the total weight, with. driver, was 10 tons 2 cwt. The observers' cabin fitted to the Daimler test chassis had an impressive instrument panel, with gauges indicating all lubricating-Oil temperatures and pressures, a speedometer, a stop watch, an electric clock and a brake-pressure gauge.

To provide ideal conditions for the short performance trials, the Daimler engineers arranged for the tests to be conducted at Lindley. The track superintendent directed us to the outer circuit of the triangular course, which is approximately three miles long. Each side measures lust under a mile and there are slight gradients; but, in the main, acceleration and braking can be tested satisfactorily on all three stretches.

First the speedometer was checked by timing the vehicle against quarter-mile posts. The greatest discrepancy in the instrument was 0.2 m.p.h. at 30 m.p.h. This was negligible and has been ignored in the test results:

The solenoid operating the brake marking pistol turned temperamental and refused to function for part of the time, so that many stops had to be made at 20 m.p.h. and 30 m.p.h. before a representative set of figures could be obtained. There was no noticeable time delay in the boost, and retardation was progressive and without harshness which might be dangerous to standing passengers. The stopping distances of 28 ft. from 20 rn.ph. and 56 .ft. from 30 m.p.h. were ample proof that the

brakes were effective, and with Tapley readings of 65-71 per cent., the system was shown to be within the maximum limit of retardation preferred by operators.

After the foot-brake trials came hand-brake tests, which provided Tapley readings of 24-25 per cent. Certifying officers are known to accept a 30-per-cent. leading with unladen vehicles, and a fully laden vehicle would be expected to have a hand-brake efficiency of 20-22 per cent.

The chassis was given its head during the acceleration tests, and speeds higher than the normal were reached. The engine fuel pump was set for high performance, and the pre-selective gearbox saved seconds in accelerating through the gears. A return of 18 secs, from rest to 30 m.p.h. indicates the power available from the Daimler engine. A 4.67-to-1 final drive and 10 00 by 20-in. tyres were fitted.

The Lindley course also proved admirable for consumption trials, because results can be reproduced without interference from other traffic and in the absence of a cross-wind there can be no variation. Our first trial was made with a stop at each quarter-mile post, tsing maximum acceleration to 30 m.p.h. between points, and braking as in normal service. At the end of five miles, the fuel supply in the test tank was replenished to the former level, the return being 8.7 m.p.g, Calculated on the time the wheels were moving, tile average running speed was 19.2 m.p.h.

Next, a test was made with a stop at each mile post, when the fuel return was 11.57 m.p g. at 28.3 m.p.h, the maximum speed observed being 35 m.p.h. Both these tests indicate that although the engine was set for maximum power, economy was not affected.

The final consumption test was made non-stop at speeds of 40 m.p.h. along the straights and 35 m.p.h. on corners. The outer-circuit curve's are nicely radiused, but the test was severe. The Freeline steering geometry provides excellent cornering characteristics, there being no evidence of tyre squeal.

The trial was stopped at the end of 10 miles and the consumption rate worked out to 12 62 m.p.g., Which, with an average speed of 36.1 m.p.h. and gross running weight of 10 tons 2 cwt., afforded a time-load-mileage

factor of 4,403 As the average factor for an oilengined single-decker is 4,200 the high performance of the Freeline is not obtained, extravagantly. Basing ell calculations on the time-load-mileage formula, the veh:cle should, under similar conditions, yield an. approximate fuel return of 16 m.p.g. at 28 m.p.h. Probably under service conditions, carrying a full complement of passengers and luggage, and with a normal flow of traffic, the consumption rate would be in the region of 14 m.p.g.

The Belgian pave was occupied, but we gathered from the log book that the chassis had already been subjected to 460 miles over the cobbles, carrying a full load and at a cost of one rear-spring breakage. Since changing to the solid-eye spring, no further casualty has been reported. The Daimler also boasts a safety clip at the spring eye and a buffer on the hangers which prevents main-leaf spread in the event of fracture. Operating temperatures had been observed, and the highest readings were recorded during the stage-service -consumption trial. With an ambient of 63 degrees F., the radiator water temperature was 160 degrees F., engine oil 115 degrees F., gearbox 135 degrees F., and final drive 130 degrees F. All these readings indicate unusually o..tol operation, but with the body fitted, temperatures would be more normal.

We returned to the works at Radford, Coventry, to refuel and check the chassis in readiness for the night run to Porlock, A test of this type is not uncommon to the Daimler engineers, and they have learnt through experience that the best time to tackle the Devon gradients is in the early morning before good and indifferent drivers pit their cars against the hairpin bends.

The party, including Mr. S. Shears, Daimler chief bus engineer, Mr. T. Wood, sales engineer, and Mr. H. Smith, assistant experimental engineer, assembled late in the evening and at' 11.30 p.m. we left Radford, with Mr_ Wood taking the first turn of driving. The weather repe‘rts prophesied rain, but a ciry spell. in the first period enabled a fast schedule to be maintained. Warwick was reached in 24 mins., and the maximum speed of 52 m.p.h. was attained on the road to Stratford, through which we passed 12 mins. later.

34 Miles in an Hour With only a few welt-laden lorries on the road, the pace was maintained to Evesham, where an I I-min. stop was called. It had taken exactly an hour to cover .34 miles to this point. Mr. Smith took control after the -break and, despite heavy rain, maintained the average. The Freeline clung firmly to the road on the bends, and within l hours of leaving Evesharn we Were enjoying well-earned refreshment under Clifton suspension bridge at Bristol.

After a 26-mM stop, "The Commercial Motor" team took a share of driving and the party reached Porlock I hour 50 mins. later Driving fast in strange country at night requires good brakes, excellent lighting and well-placed controls, all of which were found in the Daimler_ The quietness of Porlock at 4.30 a.m. was disturbed by our arrival, but peace was restored while we waited for dawn. Our first attempt on the two-mile gradient was made within half an hour, and the Daimler roared up the approach to the first hairpin bend and a sharp kick on the gear-engaging pedal brought the lowest ratio into use.

The first bend, with a 1-in-4 gradient, was negotiated at governed engine speed, and bottom gear was in full use for over 2 mins, before the incline slackened. Second gear was required for a further 21 .mins. r Altogether the intermediate ratios were employed for 1.7 miles, which were covered in 9 mins. at 11.3 m.p.h. average speed.

The initial climb brought the running temperatures up .to normal and a brake-fade test, staged on the descent, produced a Tapley reading of 59 per cent on a slight decline at the bottom of Porlock. A second climb was made without pause so that maximum temperatures could be registered and, changing gear at identical points, the time factor remained constant.

Cool. Running WiiIN an atmospheric temperature a 60 degrees F., the maximum water temperature in the radiator top tank was 162 degrees F., leaving a wide margin of safety for a similar climb on a hot day or for operation nearer, the Equator. The engine oil also remained cool. (106 degrees F.) and the hard-worked final-drive lubricant registered 160 degrees F. The gearbox temperature rose slightly to 106 degrees F.

The final assault on Porlock was made with stops to test hand-brake efficiency and the ability of the vehicle to start on severe gradients. Because of the high finaldrive ratio and large-sectioned tyres, the Daimler stood a good chance of failing but, with low gear engaged, it pulled away from rest without fuss on gradients of 1 in 61, 1 in 5, and 1 in 4. There was no difficulty in holding the chassis on the hand brake during the first two attempts, but a strong pull was required to move the pawl up another notch on the 1-in-4-section.

From Porlock we continued to Lyn mouth to climb Countisbury Hill, which is longer than Porlock Hill and is as Steep, but has no hairpin bends. After turning the chassis in the village, we headed up the long hill, and from a standing start the vehicle was soon pulling well in second gear. The speed fell as the Tapley meter registered I in 4, but the chassis kept pulling steadily in second gear. Not many coaches could climb Countisbury in that ratio.

During 345 miles of fast driving, which included a number of bills, the fuel consumption rate worked out at an average of 9.58 m.p.g.