TOP GEAR ALL THE WAY

Page 46

Page 47

Page 48

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

by John F. Moon

THE performance of the MorrisCommercial 3-tonner with B.M.C. direct-injection oil engine was so exhilarating that my only regret was that I was unable to try the vehicle with maximum load. As it was, because of short-notice arrangements before the test, the payload was only two tons.

However, the impression of power in hand was so forceful that I should imagine that the additional ton would have made little difference to the figures obtained. Acceleration that would put to shame some petrolengined vehicles of a comparable class, and a top-gear performance that on normal roads makes the indirect gear ratios almost unnecessary, have been achieved without increasing fuel consumption.

During the first I6-mile leg of the fuel-consumption trials, the route of which included the narrow and crowded streets of Kenilworth, the 3-boner was in top gear the whole time. Even when we were almost forced to come to a standstill because of a traffic hold-up, the engine pulled away steadily without having to slip the clutch. I was pleasantly surprised by the quiet running of the B.M.C. engine at all times: a vast improvement on the current sixcylindered oil engine.

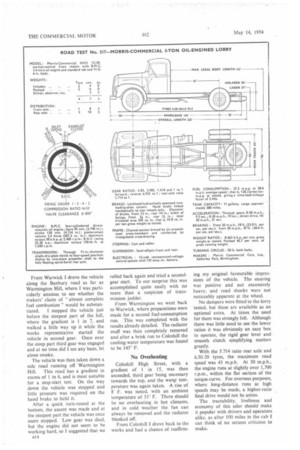

The new engine, which was fully described in the April 30 issue of The Commercial Motor, is a fourcylindered unit of conventional design having a capacity of 3.4 litres and a power output of $8 b.h.p. at the governed speed of 2,400 r.p.m.

1312 Maximum torque of 150 lb.-ft. is developed at 1,500 r.p.m., but the torque curve is almost flat from 1,000-1,750 r.p.m., which gives the outstanding top-gear performance.

Engine weight is 780 lb. The iron crankcase and cylinder-block casting carries wet cylinder liners and a fivebearing crankshaft, The main and big-end bearings are large steelbacked copper-lead shells. The side-mounted camshaft shares with the Simms fuel-injection pump a triplex-chain drive, the overhead valves being operated through pushrod and rockers. The cavity-head pistons are of aluminium alloy and are fitted with three compression and two scraper rings.

A centrifugal water pump supplies the coolant directly to the cylinder head and the cylinder bores are cooled on the thermo-syphon principle. By this means the head is kept cool while the bores warm up to working temperature quickly. The system is pressurized and incorporates a thermostat. A Burgess air cleaner is mounted on the engine bulkhead and connected by a rubber hose.

The Simms injection pump is fitted with a pneumatic governor which has dual connections to the intake-mani fold venturi. With this system, a balanced depression is maintained at the governor with a weaker dia phragrn spring, resulting in a smooth and surge-free tickover at 500 r.p.m.

A heavy-duty clutch with sprung centre plate is fitted and this, in conjunction with a Layrub coupling on the propeller shaft immediately behind the gearbox, removes all transmission harshness, especially on the overrun. The four-speed gearbox is mounted as a unit with the engine and has fairly close ratios. Four-point mounting is employed for the engine and gearbox unit, with Metalastik interleaved rubbers at the front and Metacone units at the rear. An additional cross-member is bolted into the frame to provide the front engine mounting, this being the only modification from the petrol-engined chassis. The frame side members are flat rearwards from the front axle, the dropped front end enabling the radiator to be mounted low to give good driving visibility.

A spiral-bevel final drive is fitted to the fully floating rear axle, which has a reduction ratio of 5.714 to 1. Lockheed two-leading-shoe hydraulic braking is used, and during the test I noted that all wheels locked evenly, suggesting ample braking power to cope with all emergencies. A heavier load might have reduced the tendency to lock, as I found that the rear wheels bounced.

The all-steel cab provides comfortable seating for three, the driver's seat being mounted on adjustable runners. Visibility from the driver's seat was good, engine noise in the cab was subdued and the ventilation effective.

The steering wheel is well clear of the seat and, with the wide cab doors and enclosed steps, access is easy. Instruments include an ammeter, oilpressure and fuel gauges, and a speedometer. The pedal for the mechanically engaged 12-volt starter is located to the left of the clutch pedal.

When 1 first saw the vehicle at the works, I noticed that the radiator was partially blanked off, although the day was warm, which suggested that the engine was, if anything, slightly overcooled. It started easily, and with the works representative driving, we set off for the Chester Road, Castle Bromwich, for braking and acceleration trials.

was immediately struck by the liveliness of the vehicle and we were. soon on to the clear road, where the excellent acceleration rate was confirmed by the figures obtained. Starting from rest in second gear 20 m.p.h. was reached in 9.5 sec. and 30 m.p.h. in 19 sec., results which compare favourably with petrol-engine performance.

The value of the high torque at low engine speed was shown when accelerating in top gear from 10-30 m.p.h. in 21 sec.

Braking tests were conducted along the same stretch of road, where 18 ft. was required to stop from 20 m.p.h. and 47 ft. from 30 m.p.h. Although there was a slight tendency for the vehicle to pull to the right during the first test, the brakes subsequently evened up and straight black marks were left on the roadway after each test. The Tapley meter recorded 421 per cent. efficiency when the hand brake was applied at 20 m.p.h.

The test tank was then topped up and consumption trials were made on the Warwick road through Kenilworth, a reasonably undulating route. We encountered little traffic on the way, except for the one occasion already mentioned, and after 16 miles at an average speed of 28.9 m.p.h. 44 pints of fuel were used, equivalent to a consumption rate of 29.1 m.p.g.

Later in the day, a further trial was made along the same route in the reverse direction and this time 25.9 m.p.g. was returned for an average speed of 28.3 m.p.h. Rather more traffic was encountered on this run and in order to keep the average speed comparable with that obtained on the outward run, higher maximum speeds had to be reached. Even so, the new oil engine did not show signs of being unduly thirsty, the average fuel consumption being 27.5 m.p.g. for the 32 miles at an average speed of 28.6 m.p.h. From Warwick I drove the vehicle along the Banbury road as far as Warmington Hill, where I was particularly anxious to see whether the makers' claim of "almost complete fuel combustion" would be substan tiated. I stopped the vehicle just before the steepest part of the hill, where the gradient is 1 in 7, and walked a little way up it while the works representative started the vehicle in second gear. Once over the steep part third gear was engaged and at no time did I see any haze, let alone smoke.

The vehicle was then taken down a side road running off Warmington Hill. This road has a gradient in excess of 1 in 6, and is most suitable for a stop-start test. On the way down the vehicle was stopped and little pressure was required on the hand brake to hold it.

After a quick turn-round at the bottom, the ascent was made and at the steepest part the vehicle was once more stopped. Low gear was d'sed, but the engine did not seem to be working hard, so I suggested that we 814 rolled back again and tried a secondgear start. To our surprise this was accomplished quite easily with no more than a suspicion of transmission judder.

From Warmington we went back to Warwick, where preparations were made for a second fuel-consumption run. This was completed with the results already detailed. The radiator muff was then completely removed and after a brisk run to Coleshill the cooling-water temperature was found to be 145° F.

No Overheating Coleshill High Street, with a gradient of 1 in 15, was then ascended, third gear being necessary towards the top, and the watcr temperature was again taken. A rise of 8' F. was noted, with an ambient temperature of 53° F. There should be no overheating in hot climates, and in cold weather the fan can always be removed and the radiator. blanked off.

From Coleshill I drove back to the works and had a chance of reaffirm

ing my original favourable impressions of the vehicle. The steering was positive and not excessively heavy, and road shocks were not noticeably apparent at the wheel.

No dampers were fitted to the lorry tested, but these are available as an optional extra. At times the need for them was strongly felt. Although there was little need to use the lower ratios it was obviously an easy box to operate, the rigid gear lever and smooth clutch simplifying matters greatly.

With the 5.714 ratio rear axle and 6.50-20 tyres, the maximum road speed was 43 m.p.h. At 30 m.p.h., the engine runs at slightly over 1,700 r.p.m., within the flat section of the torque curve. For overseas purposes, where long-distance runs at high speeds may be made, a higher-ratio final drive would not be amiss.

The tractability, liveliness and economy of this oiler should make it popular with drivers and operators alike, as after 100 miles in the cab I can think of no serious criticism to make.