Silencers for Internal Combustion Engines.

Page 16

Page 17

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

The methods adopted to silence and render invisible the exhaust from steam motor wagons were dealt with at length in a recent number, and the natural sequence is to the silencers which are fitted to petrol mteors. A " silencer " is also known as an " exhaust box," and in America is termed a " muffler " : its function is to allow a gradual expansion of the exhaust gases from their pressure of discharge from the engine down to that of the atmosphere. This is an extremely important question with commercial vehicles, because the public is under a general impression that they are all very noisy. It is especially imperative that the ex

haust should not be emitted in a series of loud puffs, for besiness vehicles have to load, unload, and mana2uvre among crowds of horses in narrow streets and outside warehouses. A noisy exhaust echoes very resonantly when a machine is in close quarters, surrounded by houses, or in a courtyard ; this result is magnified in a covered loading berth, such as is possessed by many city warehouses, and it would largely interfere with the work in the countinghouse or offices if no "cure " existed. It is only necessary to enter the forecourt of the Hotel Cecil, and to hear the tremendous noise made by motorcars setting down or pickingup passengers at the hotel, to realise the intensifying and reverberating effect flue to the close proximity of buildings. The exhaust resounds from the walls of this quadrangular courtyard; but in the open street it is hardly noticeable, and in the open country it is difficult to detect any noise at ail. It is, therefore, even more essential to silence the exhaust from commercial vehicles than is the case with pleasure cars. The ordinary gas engine, \vhich has been used for stationary purposes for a great many years, is a familiar form of the explosion engine, the exhaust of which must be silent. A very common practice was to take the exhaust from these engines into a box partially filled with flint pebbles. eche spaces between the pebbles formed a number of irregular expansion chambers, in which the exhaust was expanded

and baffled, v, ith the result that its discharge into the air ceased to have the nature of an explosion, but was, instead, effected gradually. There is, however, a great risk of putting considerable back pressure on the engine if the exhaust is merely baffled and retarded. In other words, it would be necessary for the piston to force the spent gases out of the cylinder on each alternate down stroke, thus absorbing seineof the kinetic energy front the fly-wheel, whereas the spent gases should find their way out from their own energy, and should not retard the engine.

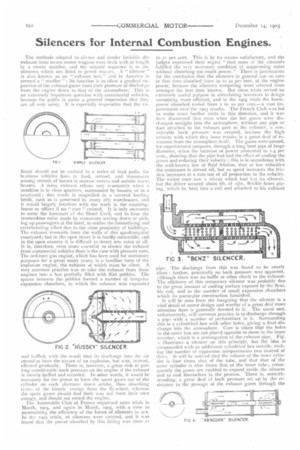

The. Automobile Club of France organised some trials in March, 1903, and again in March, 1905, with a view to ascertaining the efficiency of the forms of silencers in me. In the 1903 trials, th silencers were entered, and it was found that the power absorbed by this fitting was from ii 10 21 per cent. This is by no means satisfactory, and the judges expressed their regret " that none of the sileticets Eullillid the very necessary condition of suppressing, noise without absorbing too much power." There is justification for the conclusion that the silencers in general use on ears at that time absorbed from 20 tO 30 per cent. of the engine power, because the silencers competing were selected from amongst the best then known. But these trials served an extremely useful purpose in stimulating inventors to design something more efficient, and in the 1905 trials the horsepower absorbed varied from 2 to io per cent.—a vast immovement twer the 1903 results. The French Club was led to make some further trials in this direction, and it was then discovered that oven when the hot gases were discharged straight into the atmosphere, without any pipe or duct attached to the exhaust port at the cylinder, a considerable back pressure was created, because the high velocity with which they issue results in a great deal of resistance from the atmosphere itself. The gases were passed, for experimental purposes, through a long bent pipe of large diameter, when the increase of power amounted to 1.4 per rent., showing that the pipe had had the effect of cooling the gases and reducing their velocity : this is in accordance with the well-known law of fluid friction, that at low velocities the resistance is almost nil, but as speed increases the friction increases at a rate out of all proportion to the velocity. The writer once saw a tri-car which had lost its silencer, but the driver secured about oft. of 'tin. flexible brass piping, which he bent into a coil and attached to his exhaust pipe. The discharge from this was found to be nearly silent : further, practically no back pressure was apparent, although there was no baffle or other check to the exhaust. The efficiency of this temporary silencer was probably due to the great amount of cooling surface exposed by the flexible coil, and to the number of small expansion chambers which its particular construction furnished, It vill be seen from the foregoing that the silencer is a vital detail of motor design and worthy of a great deal more attention than is generally devoted to it. The usual and, unfortunately, still common practice is to discharge through a pip:: with a number of perforations in it. Surrounding this is a cylindrical box with other holes, giving a final discharge into the atmosphere. Care is taken that the holes in the outer box are not placed opposite to those in the inner member, which is a prolongation of the exhaust pipe. Fig. I illustrates a silencer on this principle, but the idea is compounded with an additional cylindrical box outside, making the number of expansion compartments two instead of three. It will be noticed that the volume of the inner cylinder is four times that of the tube, and that that of the outer cylinder is nine times that of the inner tube; consequently the gases are enabled to expand inside the silencer and to cool themselves in the process. There is, notwithstanding, a great deal of back pressure set up by the resistance to the passage of the exhaust gases through the holes, and this very simple form of silencer cannot be recommended on the score of efficiency. Fie.. 2 illustrates a silencer known as the Hussey, in which the operation is reversed. The exhaust gases enter through the screwed orilice, and immediately come in contact with a baffle plate, which deflects them to the outside of the silencer. After passing this baffle plate, they enter a large expansion chamber, then rind their way through some holes into a central tube, and, finally, from it to the atmosphere. This silencer is far in advance of the other form, because the hot gases come in contact with the large exterior surface ot the outer shell, whereas in the form illustrated in Fig. i they do not reach the outside plate until the last stage. The same system will be found further elaborated in Fig. 3, the Benz silencer, which consists of a somewhat peculiar casting, and an outside casing. The exhaust gases pass from the engine through a series of holes into the first half of the silencer ; they next have to pass through a number of tubes in the division plate to reach the second half of the silencer ; lastly, before making exit to the atmosphere, they are obliged to enter the interior pipe through a series of holes. The same idea is carried out in Fig. 4, with but a slight variation : this is the Abingdon silencer. It consists of a cylinder, divided into two unequal parts, and having a tube through the middle. The exhaust gases enter the first half and pass through a number of small holes into the central tube. They leave the other end of the central tube through similar holes, and expand in the other chamber, from which they find their way to the atmosphere by a number of holes in the end plate. It will be observed that the gases get two distinct expansions—one when they leave the exhaust pipe and enter the larger chamber, and another when they leave the central tube and enter the second chamber. This silencer also ex. poses a large surface to atmospheric cooling. In purchasing a silencer it is important to see that proper provision is made for cleaning, as the exhaust gases will always contain a certain amount of burnt oil, which will be deposited on every possible surface, and this may be very considerable if any serious excess of oil is fed to the cylinders. In all the .silencers illustrated, with the exception of Fig. 3, the ends are made removable, so that it is quite simple to clean out the various cylinders. In the Benz silencer (Fig. 3), the outer casing can be removed by unbolting a longitudinal joint.

Allusion has already been made to the silencer trials which were conducted by the French Club in 1903. The first prize was awarded to Messrs. Ossant Freres, the second to Mons. de Retz, the third to the Moto-Car Company of Nice, and a fourth prize to a second silencer submitted by Messrs. Ossant Freres, In considering the merits of the

13 silencers which were submitted in competition—t6 were entered, but three of them were not presented—the judges had to take into account the reduction in the noise of the exhaust, and also the back pressure produced. They further had, by some system of marking, to give due expression to considerations of the space occupied, and the weight, simplicity, and economy of construction. Fig. s represents the Ossant Freres silencer which obtained the first prize. It will be noticed that it is closely similar to that which is illustrated in Fig. t,. but that the process is repeated in the second half in the reverse order. This silencer absorbed II.i per cent, of the engine power. The de Retz silencer, which was placed second, is illustrated in Fig. 6 : this absorbed 12.2 per cent, of the power, and it will be seen that the gases enter a large circular drum, where they expand before splitting up in various directions into a number of currents. Some gases can immediately pass sideways into the central tubes at each end, and some can pass through hotel; on the opposite side of the central tube and then through the batffle plates into the end tubes : the baffle plates completely break up and churn about the currents of gas. Front the central tube, the gases pass outwarffs by a very similar system to that of Ossant Freres, but the process is not reversed, and they are allowed to escape into the atmosphere from the outside cylinder. The central tube, which is shown separately in section, is ribbed on the outside, with a view to a further splitting up of the currents. The device which obtained the third prize, and which is not illustrated, consists in passing the exhaust through iron filings. This was extremely efficient in suppressing the noise, but it absorbed 20.6 per cent. of the power ; it was, moreover, found extremely difficult to prevent the iron filings front blowing out. The other devices submitted did not present such novelty, but the Ravel silencer, illustrated in Fig. 7, which is made by Linzeler and Co., of Paris, presents an interesting.modification of the simple silencer shown in Fig. z. It will be noticed that there are the same three expansion chambers,

but that all are conical, and that the gases pass through in the reverse order—i.e., from the outside towards the inside, The exhaust enters by a passage, which is spiral in shape, so that the helical motion will be kept up all the way through the outer chamber, and will thoroughly churn up the exhaust gases. The gases are continually passing from a large chamber into a smaller, which has the undesirable effect of increasing, instead of decreasing, their velocity, although the churning and baffling will make the emission continuous instead of intermittent. It is probably from this cause that the back pressure proved to be very high, and that this device did not succeed in obtaining an award in the trials. At the conclusion of the trials, the judges issued and published a very full report : the loss of power front inefficient silencers was thus brought home to the trade. Manufacturers for the first time realised that something more was wahted than the mere suppression of noise, and many brains were set to work to devise a silencer that would not cause back pressure. It is intended in a future number to explain the improved forms that have resulted.

(To be continued.)