TABLE II

Page 23

Page 22

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

,leage Results of a Variety of Checks on Certain

spec t of 'Tonmi

Wages and Subsistence Allowances

Applying the Principles Which Have Been Enundated in Previous Articles to a Problem That is Somewhat Different From Any That Have Yet

Been Considered

THE articles on ton-mileage which have recently been appearing, have, evidently, attracted a good deal of interest. Several correspondents have written to me and most of them are appreeiative of the way in which the subject has been treated.

One asked me in what way the .ton-mile, as I described and defined it, differed from the per-ton per-mile which is stated to be the basis of what has now come to be known as . the Leeds Schedule for long-distance haulage, a schedulewhich, I understand, is being considered by the Road -Section of the Road and Rail Conference as a 'basis for stabilized rates.

The answer to that question is that the per-ton per-mile as theredefined is, in fact, the capacity ton-mileage of the vehicle, assuming it to he fully loaded. Without going into detail and without direct reference to the records I have relating to theLeeds Schedule, I should say, writing from memory, that the basis of the Leeds Schedule was the work which could be done by a 6-tonner, assuming it to be fully loaded in one direction, and returning empty.

. Apart from the question of weightage which, as I have already. stated is not, in my opinion, capable of application to a schedule for long-distance haulage, the Leeds Schedule is calculated by assuming that a 6-ton vehicle operates at a given cost per mile run plus certain allowances for terminal charges. Assuming that 18d. per mile is the net cost (which, of course, is 3s. per two miles run), then the cost peilton per-mile is one-sixth of 3s. (the total cost per lead-mile), which is 6d.

For example, assilnaing a journey of 200 miles with a 6-ton load the vehicle returning empty, the ton-mileage is, of course, 1,200. The cast, at Is. 6c1. per lead-mile, is 600S., so that the cost per ton-mile is 6d., whilst the cost per ton is £5. .

• More interesting is the problem raised by another correspondent, who tells me that he has been endeavouring to arrive at some comparative figures to show the work done by certain of his vehicles over a 12-weeks' period. In making these calculations, he says, he was not so much concerned with comparing individual vehicles as in obtaining some statistical data relating to the work of the fleet as a whole. .

As a preliminary he, first of all, obtained gross weekly totals under the following headings:—(1) Number of vehicles operating; (2) Total weight carried; (3) Total mileage loaded: (4) Total mileage empty; (5) Wages cost, i.e., all men employed on the specified vehicles; (6) Subsistence, employees' insurances, and expenses incurred by drivers while an the road; (7) Weight carried per 1-ton vehicle capacity. .

Data of the naturg disclosed in this investigation are set out in Table I. It should be noted that a fleet of 10 vehicles, apparently all of them 8-tonners, is under consideration. He found no great difficulty, he tells me, until he came to the problem of 'resolving, from this collected information, the figure for wages and subsistence cost per

tori-mile, which was what he.really wanted. He. tried several methods of obtaining that information without coming to a satisfactory conclusion.

In the first place he decided to ignore mileage, and worked out the figures at cost per ton carried. We will do this in conriection with the first example. The total load carried was 376 tons 8 cwt., and the cost for driver's wages and subsistence allowances svas.£100 us. 10d. The result is 5s. 4d. per ton. .

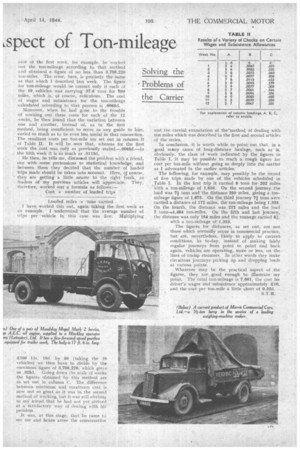

The total of his calculations for 12 weeks, according to that method, is shown in column A 'of Table II, and it is there seen, as My correspondent states in his letter, that there is no utility in his figures: theytell him nothing. There did not appear to be any relation, whatever, between the tonnage or the mileage and the cost per ton carried. The only outstanding figure is that for the fifth week when, for some reason or Other, the tonnage was low and the mileage, perhaps, a little below average and the eost per ton was 7s. 8d.—a higher, figure than for any other week.

Apart from that example, however, the fluctuation was not sufficient to give any indication as td where the expenditure was excessive or otherwise. Even in the case of the sixth week, where the mileage is particularly low and the tonnage average, the cost per ton did not fall to any great extent, being only 4d. below the first example when the tonnage was average and the mileage next to the highest of those registered. He tells me that, in his opinion, the futility of the figures thus obtained is due to the fact that greater weights.appear to be carried a greater distance, thus costing more per trip in wages, with the result that the cost per ton differs but little.

It was at this stage that he began to try to think in terms of the ton-mile and, in the first application, he made the usual mistake to which I have referred frequently in this short series of articles, i.e., he multiplied the weight carried by the loaded miles. He divided.this into cost and obtained figures that were obviously absurd. In the

case, of the first week, for example: he worked out the ton-mileage according to that method and obtained a figure of no less than 3,708,226 ton-miles. The error, here, is precisely the -same as that which I described last week. The figure for ton-mileage would be correct only if each cif the 10, vehicles was carrying 37.6 tons for 980 miles, which .is, of course, ridiculous. The cost of wages and subsistence for the ton:mileage calculated aCcording to that process is .0065d.

Moreover, when he had gone to the trouble Of working out these costs for each of -the 12 weeks, he then found that the variation between one and another, instead of, as in the first method, being insufficient, to serve as any guide to him, varied so rriuch as to be even less useful in that connection. The resultant costs per ton-mile are set out in column. 33 of Table II. It will be seen that, whereas for the first week the cost was only as previously state4--.0065d.—in the fifth week it is as much as .0113d.

Ile then, he tells me, discussed the problem with a friend, one with some pretensions to statistical knowledge, -and between them they decided that the number 'of loaded trips made should be taken into account. Here, ot course, they are getting a little nearer to the right track; as readers of my previous articles will appreciate. They, therefore, worked out a formula as folloWs: Cost number of loaded trips

• , Loaded miles rx • tons carried have worked this out, againtaking the first week as an example. I understand that the average number of trips per vehicle in this case was five. Multiplying E.100 1 Is. 10d. by 50 (taking the 10 vehicles) we then have to divide by the enormous figure of 3,908,226, which giveS us .325d. Going down the scale of weeks the figures obtained by this method are ds set out in column C. The difference between minimum and maximum cost is nOw not so great as it was in the sedond method of working, but it was still obvious • to my friend that he had not yet arrived;',.. at W satisfactory way of dealing withfiji problem.

It was, at this stage, that he came ti see me and hence arose the conversation and the careful enunciation of themethod of dealing with ton miles which was described in the first and second articles of the series.

In conclusion, it is worth while to point out that, in a

• good many cases. of long-distance haulage, such as is, obviously, the class of work indicated by the figures in Table I, it may be possible to reach a rough figure for cost per ton-mile without going so deeply into the matter as I advocated in the earlier articles.

The following, for example, may possibly be the record

of five trips made by one of the vehicles scheduled in Table I. In the first trip it carried 8 tons for202 miles 'ivith a ton-mileage of 1,616. On the second journey the load was 7+ tons and the distance 250 miles, giving a ton. mileage figure of 1,875. On the third journey 7i tons were carried a distance of 172 miles, the ton-mileage being 1,333. On the fourth, the distance was 212 miles and the load 7 tons-4,484 ton-miles. On the fifth and last journey.,

the distance was only 164 miles and the tonnage carried 8,f, with a ton-mileage of 1,353. •

The figures. for distances, as set oirt, are not

those which normally occur in commercial practice, but are, nevertheless, likely to apply, td current. conditions, 'as to-day, instead of making fairly regular' journeys from point to point and back again, vehicles are operating, more or less, on the lines of tramp steamers. In other words they make circuitous journeys picking up and dropping loads at various points.

, Whatever may be the practical aspect of ;the

figures, they are good enough to illustrate my point. The total ton-mileage is 7,661, the cost for driver's wages and subsistence approximately LIO, and the -cost per ton-mile a little short-of 0.32d.

S.T.R.