Solving the Problems of the Carrier

Page 28

Page 29

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

Assessing Costs for Parcels Carrying

Third Article of a Series, Including the Story of the Way in Which a Beginner in this Business Built Up His Clientele

IN the previous articles I have indicated the types of express-carriers' business, pointed out the importance of co-operating with other carriers in order to ensure succez, and briefly indicated the most important of the condition's of carriage to which the haulier should adhere when carrying parcels.

I pointed out that the propel way to deal with the subject of costs and profits is first of all to decide a rate, preferably one which is already customary in the district, afterwards assessing costs. Then, having in view the probable volume of traffic, the operator Can decide whether the project is going to be profitable or not I su-ggested ways of incraasing business and concluded with suggestions for what I might call paper work; that is to say, records and statistics

which the parcels carrier shOuld keep. • 1 now come to something which is equally iinportant; that is, to indicate the sort of things Which the operator should not do if he hopes to make his business a success.

• (1) He should be careful not to give signatures without qualifications for goods already damaged. (2) He should avoid signing for goods before they are actually loaded. (3) He must be careful, when loading his vehicle, not to put heavy goods or packages on top of, or against, goods marked "

glass" or " fragile," or-against goods which he knows to he fragile and liable to injury if humped. (4) He must not load piece goods so that they are in contact With other cornmoditieS which will soil them; they should not-be loaded on to a dirty van or lorry floor. (5) He should avoid rough handling, which may cause rents in coverings, 'breakage of string, and exposure of contents of packages or parcels. (6) He should be careful not to collect miscellaneous or general traffic without consignment notes, Or without the goods being marked in any way as to sender Or destination or not showing correct sender. (7) He must avoid picking up goods for towns and outside areas not covered by his own services or by those of associated companies. (8) He should not pick up Miscellaneous goods without information as to who pays the carriage. (9) He should never accept goods of a highly damageable naturewithout packing, or without comment as to such goods being accepted at sender's risk Only. (10) He should avoid consignment notes and collection sheets not handed in and entries omitted from collection sheets.

• Unloading and Reloading Conditions When unloading or reloading on depot premises, particular attention should be paid .t.o items 3, 4, and 5, and the following should be avoided :—

(11) Goods unloaded and put in wrong traffic area. (12) Goods loaded insecurely, resulting in packages falling off; particularly in open lorries. (13) Goods loaded without entries on delivery sheets. . (14) Wrong quantities delivered (either more or less) against • delivery sheet entries. (15) Delivery to wrong addresses or firms, in spite of the label gr'eing correct particulars. (16) Goods brought hack as being wrongly addressed and subsequently found to. be correetly addressed, (17) Cash for carriage to collect and C.O.D. items not collected. (18) Goods brought back and unloaded,: no report being made as to reason why. (19) No report made regarding discrepancies on delivery sheets. (20) .Delivery sheets not handed in, (21) Delivery sheets mit initialled, indicating by whom the sheet was received. (22) Signatur for goods accepted, which cannot be deciphered.. *

The next point to Consider is the cost of operation and . to compare it with the probable revenue, having in mind agreed schedules of rates. In this connection, I should make it clear that I do not propose to concern mys'elf with the work of large organizations.. This article is written for the small man and especially for newcomers to the business. I have in mind owners of front one to six vehicles. 1 will start by taking a typical example. In principle it well indicates the experiences which are likely to come to the small man who is just beginning, and it is worth while relating at length.

In the course of telling this story, I shall have to 'etal with the problem of co-operation with other parcels carriers ----the advantages and pitfalls of such a procedure. That, as a matter of fact, is all to the good, because such co-operation is essential to success in almost every case.

The central figure is a small operator starting in a very modest way. He lived in ali area whickreally was " truly rural." I-le found that the market-gardeners there had difficulty in getting their produce conveyed to the nearest industrial centre and market, a city some 32 miles away. He had had some training as a motor mechanic, but beyond.

• that, and, of course, the ability to drive a motor vehicle, he had no special aptitude for the business.

In those days there were no restrictions on private enterprise by people desiring to enter the haulage industry, which is only another way of saying that the Road and Rail Traffic Act was not then in force. •

, He started, then, as many of thoee who are big operators to-day started, by the purchase of a used light van, and with it supplied a public need by conveying the produce of the local market-gardeners to the big city.

He soon found that there were other angles to _the business than this, other purposes to be served, other customers to be satisfied. In the first place, the original customers needed supplies from the big city—seeds, manures, and so on. Then tradesmen in his village, learning of his project, began to utilize his facilities to bring iii their goods. A small local manufacturer began to use his services. In little time tie discovered that his original light van was inadequate for his . needs, so he rep/aced it by a 30-cwt. van.

The Minimum-capacity Vehicle All this was before I met hint, which was unfortunate for him, for had he come to me in the early Stages I would have offered him the advice already given in this short series of articles on parcels-carrying; namely, that a 2-tonner is the minimum-capacity vehicle for such work. He was disappointed with his 30-cwt, vehicle, because its body was, too small. He told me, when eventually I did meet him, that an operator in his line of business must be able to cater for bulk rather than weight, because it is the bulky parcels which people like to hand over to the carrier.; • However, he made do with this vehicle for a while, principally because -he could not immediately afford' the change. Sarin he discovered the advantage, if not the necessity, of entering into agreements with other parcels carriers. An express-carrier concern, of some pretensions to size, had its headquarters in the big city, which I will call Bluepool. This company operated a number of routes radiating from Blnepool, but was not interested in that over which my friend was Operating. It was desirous of Some service to my friend's village, which I will call Barborough. 11.e company was agreeable to use his services, and the terms Of the agreement were as follow :—

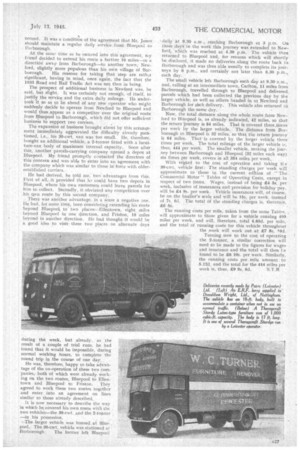

In the first place, they agreed that my friend, whom I will call Mr. Jones, should make use of the company's depot in Bluepool. His customers cduld if they so desired, deposit their parcels there for his collection. For this service the large company charged a_commission of 20 per cent. of the • total charge for the conveyance of the parcels so depbtited, On /the other hand, Mr. Jones was -10 take oOre of the large crimpany's traffic from Blnepool to Barborough, and fcr that service was to receive 40 per cent, of the rate charged for the parcels so carried. • The termsdo not seem -to be particularly generous, especially so far as the latter part of the agreement is eon?. cermet It was a condition of the agreement that Mr. Jones should maintain a regular daily service from Aluepocl to Ha [-borough.

At the sarn, time as he entered into this agreement; my friend decided to extend his route a further 10 miles—iie a direction away frem Barborough—to another town, Newford, slightly more populous than his own village of Bar borough. His reasons for taking that step are rath,er significant, having in mind, once again, the fact that the 1933 Road and Rail Traffic Act was not then in being.

The prospect of additional business. in Newford was, he said, but slight. It was certainly not enough, of itself, to justify the service and the extra daily mileage. He undertook it so as to be ahead of any new operator who might suddenly decide to operate from Newford to Bluepool and would thus appeat as a competitor over the original route from Bluepool to Barborough, which did not offer sufficient business to support two carriers.

The expansion of business brought about by this arrangement immediately aggravated the difficulty already pentioned, Le., his 30-cwt, van was too small. He, therefore, bought an additional vehicle, a 2-tonner fitted with a furniture-van body of maximum internal capacity. Soon after this, another parcels-carrying company opened a depot at Bluepool. My friend promptly contacted the directors of this concern and was able to enter into an agreement with the company which was similar to those in' force with olderestablished carriers.

He had derived, he told me, two advantages from this. First of all, it provided that b:r could have two depots in Bluepool, where his own customers could leave parcels for him to collect, Secondly, it obviated any competition over his qwn route by this second company.

There was another advantage, in a Sense .a negative :me. Ile had, for some time, been considering extending his route beyond Bluepool, to' two places—Ellentown, eight miles beyond Bluepool in one direction, and Friston, 10 miles beyond in another direction. He had thought it would be a good idea to visit these two places on alternate days

during the week. but already, as the result of a couple of trial runs, he had found that it would be impossible, during normal working hours, to complete the round trip in the courae of one day.

He was, therefore, happy to take advantage of the co-operation of these two companies, both of which were already wo;king on the two routes, Bluepool to Ellentown and Bluepool to Friston. They agreed to work these two routes together and enter into an agreement on lines similar to those already described.

it is now necessary to describe the way in which he covered his own route with tire .two vehicles—the 30-cwt. and the, 2-tonner —in his possession.

The larger vehicle was housed at Bluepool. The 30-cwt. vehicle was stationed at

Barborough The former left Bluepool daily at 9,30 reaching Barborough at 3 p.m. On

three...days in the week this journey was extended to Newford, which was reached at 4.30 p.m. The vehicle then returned to Bluepool and, for reasons which will Shortly be, disclosed,. it Made no deliveries along the route back to Barborough and was thus able usually to complete its journeys by 6 p.m., and certainly not later than 6.30 p.m., each day.

The small Vehicle left Barborough each day at 9.30 a.m., and, calling at an intermediate town, Carlton, 11 miles from Barborough, travelled through to Bluepool and delivered -parcels which had been collected the previous day by the .larger vehicle, as well as others handed in at Newford and Barborough for stich delivery. This vehicle also returned to Barborough the same day.

Now, the total distance along the whole route from Newford to Bluepool is, as already indicated, 42 miles, so that the return 'journey is 84 miles. That is covered three.thres per week by the larger vehicle. The distance from Barborough to Bluepool is 32 miles, so that the return journey is 64 miles, That is covered by the larger vehicle three times per week. The total mileage of the larger vehicle 0. thus, 444 per week, The smaller vehicle, making the journey between Barborough and Bluepool (32 miles each way) six times per week, covers in all 384 miles per week.

With regard to the cost of operation and taking tl.e 30-cwt. vehicle first: The standing charges per weekviill approximate to 'those in the current ecation of " The Commercial Motor " Tables of Operating Costs, except in respect of two items. Wages, instead of being £4 Ss. per week, inclusive Of insurances and provision for holiday' pay, will be £4 9s. per week. Vehicle insurances will, of course, be on the haulier's scale and will be 15s, per week, instead of 7s, 6d. The total Of the standing charges is, therefore, £65s.

The running costs per mile, taken from the same Tabb.s, will approximate to these given for a vehicle running 400 miles per week, and will, therefore, total 4.65d. per mile, and the total of running costs for this vehicle throughout the week will work out at £7 8s. :10d,

Turning now to the cost of operating the 2-tonner, a similar correction will need to be made to the .figures for wages and insurance and the total will then in found to be £6 10s. per week. Similarly, the running costs per. mile amount to 5.12d, and the total for the 444 miles per week is, thus, £9 9s. 6d. 'ST. R