Leyland Freightline Beaver 30-ton-gross artic

Page 48

Page 49

Page 50

Page 53

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

by A. J. P. Wilding, MIMechE, MIRTE

(turbocharged)/Scammell

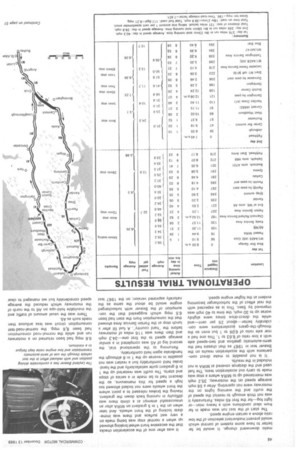

IF I needed proof of the advantages oj a high-power turbocharged engine and semiautomatic transmission it was given me by the test of a Leyland Beaver BV69.32PTR which I have just completed.

Running at a gross combination weight of 30 tons, the vehicle completed CM's 731mile operational-trial route in a total running time of less than 18ihr and with a very low noise level and reduced effort through the easy gear change, the driving—shared by Derek Heaton of Leyland and myself—did not produce anything like the fatigue that one would have expected at the end of it. If there is to be improved productivity in goods transport in conjunction with shorter driving hours, it is this sort of vehicle that will make it possible.

To put the type designation of the test machine in understandable terms, the tractive unit was the 9ft Gin, wheelbase Beaver with 240 bhp gross turbocharged 680 engine (the 690) and 10-speed semi-automatic gearbox featured by Leyland at the Commercial Motor Show. For the test it was coupled to a Scammell 28ft long tandem semi-trailer. The outer-axle spread limited the gross weight to 30 tons although the model is designed to operate at up to 32 tons gross combination weight, but this weight was accepted so that comparisons would be possible with results from an earlier test at 30 tons of a Beaver with the same specification but a naturally aspirated 680 (CM, April 28 1967). The turbocharged Beaver gave an extremely good account of itself with fuel consumption be

tween 5.1 and 7.25 mpg for an overall figure of 6.21 mpg.

The journey was completed in a shorter time than on previous tests of the same type and it will be seen from the results table that the 376-mile northern leg to the approaches of Edinburgh was made in 9hr 23min with the second day's run of 355 miles needing only 8hr 58min. Average speed on the first day was just over 40 mph and on the second just under for an overall average of 39.9 mph. And while the use of the high-power engine was a major factor in allowing these figures to be returned, so was the semi-automatic transmission which enabled the gradients to be climbed in shorter times than would have been possible with a manual gearbox. What is more important instantaneous ratio changes enabled the normal running speed to be reached much more quickly after them.

It must be taken into account when considering the average speeds returned that legal maximum road speeds are observed on these tests. On the motorways which represent about half of the total distance, the Beaver was driven at its maximum speed of 60 mph where possible but elsewhere the speedometer needle was never allowed to go more than 10 per cent above the 40 mark. It was in fact something of an effort to hold the Beaver back on roads such as Al and 40 mph seemed a walking pace especially with most of the other goods traffic going past us quite smartly. To break down the route into the different types of road, there are almost 350 miles of motorway, about 130 miles of good-quality A roads and about 250 miles of heavily trafficked or hilly stretches, the worst of the latter being A68.

It would have been nice to be able to say that the Beaver is a perfect vehicle but against the advantages of a quiet engine, easy gear change and generally comfortable cab, I have criticisms of low-standard steering, a heavy accelerator pedal and less than satisfactory braking characteristics. I feel that power steering is necessary with a front-axle load of 5 tons or above but it was not just the heaviness of the steering on the Beaver. The effort needed to turn the wheel varied from paint to point and it was necessary to make fairly continuous corrections to the wheel to maintain the chosen line.

The last inch or so of movement of the accelerator pedal called for a good deal of effort. Up to this point the action was quite light and keeping the pedal against the extra pressure rather than its stop allowed speed of about 53 mph to be maintained with no strain on the right leg muscles. This is not such a bad thing really as a driver would not be inclined to maintain maximum speed for longer than absolutely necessary. But the aim on a test of this sort is to assess the maximum potential of a vehicle which requires pushing a vehicle to its limit. I would have liked to be relieved of the effort required to maintain full throttle and I must admit that if I had accepted the temptation and had Derek Heaton do the same, less than 1hr would have been added to the total time. As an incidental advantagd it would also have meant less need to be concerned about the activities of other users on the motorways for it is suprising the amount of baulking from other traffic when one is trying to maintain 60 mph as compared with running at a maximum of 50 mph or so.

Because it was understood that the only difference between this test vehicle and that tested in 1967 was in respect of the engine it was decided to carry out the long-distance operational trial and only those other tests that would be affected by the power-unit change. To give a picture of all aspects of the Beaver, however, the results of brake tests carried out in 1967 are included in the accompanying table. As the test vehicle turned out to have a different front axle with bigger brakes than before, the braking figures quoted will not necessarily apply to the current test machine but if it had been planned to take figures very wet roads at the time made such tests impracticable.

Results obtained by Leyland and the -feel" of the performance when braking heavily indicated that the test model should give at least as good figures as the earlier machine. The criticism I have on the brakes is not in this connection, it is that there appeared to be too much effort applied at the front axle which caused undue locking of the front wheels on wet (low-adhesion) surfaces. There was also some delay in the brake system and taken together these two factors did not engender a feeling of confidence when braking.

I suspect that there was something not completely right with the driving axle brakes or those on the trailer although this has not been confirmed by Leyland. The front-brake sizes do not appear to be excessive and the brake proportioning would appear to be similar to that employed on other modern artics that I have tested and which have given good braking characteristics.

Use of a turbocharged engine in this latest version of the Beaver is not a new departure for Leyland as the company has been supplying vehicles with turbocharged engines to various parts of the world for many years. The. output of 240 bhp gross CBS. AU141) is obtained at a speed of 2,200 rpm and the maximum torque is 650 lb.ft. at 1,400 rpm. As is usual with a turbocharged engine it is necessary to keep the engine speed on the high side to obtain the maximum performance and in the case of the Leyland unit I found the ideal point to change down when ascending really steep hills was when the engine speed dropped to 1,800 rpm although this could be reduced to about 1,500 rpm according to the severity of the gradient. The Leyland semi

automatic gearbox with integral built-in splitter gives 10 fairly evenly spaced ratios from a 7.25 to 1 bottom gear to a 0.77 to 1 top. Maximum speeds in the gears when splitting each main ratio were 7, 9, 12, 15, 19, 25, 29, 38,46 and 60.

Besides the engine there has been a change to the handbrake and secondary brake system for the turbocharged Beaver. The system as used on the new Lynx tractive unit is employed with spring brake chambers at both axles. Actuation of these two systems is by a secondary/parking valve mounted on the instrument binnacle and the first position reached with this component is the secondary when the air pressure holding off the springs on the front axle actuators is exhausted at the same time as the auxiliary line to the semitrailer is pressurized. Moving the lever to the park position exhausts the air to the semitrailer and also the air behind the springs in the driving axle to leave both axles braked for parking. Load-sensed brakes are standard at the driving axle.

Ratio changes in the semi-automatic box are made through a small control lever working in a six-position gate. As soon as the lever is moved to its new position the ratio is changed and the splitter section is selected by a small switch on the knob: There is a protection in the "gate" to prevent inadvertent selection of second gear from fifth; to get into the second and third positions the lever has to go into fourth first. This prevents excessive over-speeding of the engine and possible serious damage but it is still possible to make an error—for example selecting third from maximum speed in fourth instead of fifth—and it is also possible to change the splitter section at the wrong time.

On the test we uncovered a possible trouble spot in this connection. I was driving at about 60 mph in top gear and when I moved the flasher control to overtake, the splitter section changed down to the low ratio by itself causing the engine to speed up to about 3,000 rpm. Fortunately no damage was caused but I pulled over to the hard shoulder of the motorway to find the trouble; we had lost the facility to change the splitter section. There was obviously an electrical fault but inspection of the connections revealed no trouble and then we found we cguld change the splitter again. After the test a . check by Leyland brought to light a chafed wire in the switch feed which was the cause of the trouble. But clearly there is a need for some alteration in the design; if there is an electrical fault there should be no chance of a.-1 auto

matic downward change. It would be far better to have some system of control which would prevent inadvertent selection of the low ratio above a certain engine speed.

The start of the test run was made in far from ideal conditions with a heavy mist-or light fog-for the first 45 miles. Fortunately it was not thick enough to restrict the speed of the outfit and the warning lights on the motorway were not operating. After a 56 mph average speed on the motorway, 35.2 mph was maintained up to MIRA where a stop was made to carry out acceleration tests. The fuel used and the distance covered at MIRA is not included in the results.

It is not possible to make direct comparisons with the acceleration results on the Beaver test in 1967 as that chassis had the semi-automatic gearbox and two-speed axle with a low ratio of 6.63 to 1. This one had a rear axle ratio of 6.06 to 1 but even so the through-the-gears accelerations were considerably better-about 25 per cent-and while the direct-drive times were slightly worse up to 30 mph, the time to 40 mph was improved by 5sec. This is as expected with the real effect of the turbocharger becoming evident at the higher engine speed. It was after one of the acceleration checks that the excessive front-wheel braking showed up when a normal stop was being made on a very wet surface and there was immediate locking of the front wheels. And later when on the 1 in 5 gradient on MIRA after an unsuccessful attempt at a climb there was difficulty in running back down the gradient. Having the brakes released to a point where the front wheels were not locked allowed too high a speed for this manoeuvre, so the descent had to be made in a series of stops and starts. The outfit was restarted up the 1 in 6 gradient quite satisfactorily and the handbrake held comfortably but a restart was not possible in reverse up the 1 in 6 although the handbrake again held comfortably.

Returning to the operational trial, the second leg of AS was completed in a similar average speed to the first one-34.3 mph and then there was 116 miles of motorway before the "hard country". A fuel fill after a lunch stop at the Forton Service Area showed that the consumption from the start had been 6.5 mpg which suggested that the consumption of the Beaver with turbocharged engine would be about the same as the naturally aspirated version; on the 1967 test 6.6 mpg had been returned on a motorway run and while the normal-road consumption had been 8,6 mpg, the normal-road-test consumption circuit was less arduous than roads such as A5.

There was the usual amount of traffic and the inevitable hold-ups on A6 to the north of the motorway which reduced the average speed considerably but we managed to clear the last of the slow movingartics just at the start of the climb of Shap and we then had a clear run. At the Jungle 'Café the vehicle speed was 25 mph and the time taken for the 4.25 mile climb to the summit was '8min 3.4sec. The general speed for the climb was between 15 and 20 mph and on the steepest-1 in 9—section the speed dropped to 13 mph in second /high. At the top the road speed was 33 mph.

Traffic after Shap was reasonably light and the new Penrith by-pass saved going through

that town I would estimate that the by-pass saved at least 10min. But progress through Carlisle was slow and the same applied for the 10-mile stretch from there to Gretna.

After Gretna where another fuel stop was made-6.5 mpg from Forton—we were in the dark but the high standard of A74 made the run to Beattock something of an amble at the 40 mph maximum.

Between Beattock and Dalkeith we went over the Tweedsmuir hills but even so the average was 33.4 mph and here we turned south for 4 miles—most of it uphill—to the overnight stop at Pathhead.

The Beaver made light work of the first 60 miles of A68 the next morning including the two-mile climb of Carter Bar which it romped ()tier at 20 mph for most of the way in third /high. This gear was just right for the gradient which is 1 in 13 /14 for most of the way but near the top where the slope increases to 1 in 10, third /low had to be engaged for a short distance and the speed dropped to 16 mph. Total time for the climb was 5min 32.6sec. The really heavy part of A68 starts at West Woodburn where the long gradient has a maximum slope of 1 in 6.5 and from there to Consett there are frequent gradients of 1 in 8 and 1 in 9 including Riding Mill with a maximum of 1 in 5 and the hill just before Castleside where the turn on to A691 is made which is 1 in 5.25 at the steepest.

It is not possible to take a run at Riding Mill because of the sharp turn at the bottom and from about 5 mph at the bottom the 0.6-mile climb of the hill took 3min 6sec with 15 mph the reading at the top. A slow change to bottom on the 1 in 5 section brought the outfit almost to a standstill. But the engine pulled the Beaver over this steepest section in first /low and although the road was wet at the time there was no wheel spin.

The hill before Castleside is 0.8-miles long and again there is no chance of a start because of a fairly tight bend at the bottom after a long down grade which has to be taken in a low ratio fairly slowly. The time taken to cover the gradient was 3min 35.6sec with first/high required on the 1 in 5.25 gradient and the speed down to 5 mph. After this the gradient eases out and at the top of the hill the speed had risen to 12 mph.

Up to West Woodburn average speed for the two hours' driving had been 31 mph and on the more' difficult stretch there was not much of a drop—to 25.6 rr ph only—which illustrates the way in which the Beaver dealt with the "hard stuff". After Consett it was all relatively easy going with 31.4 mph maintained on the single-carriageway section of Al. And after the 17-mile Darlington by-pass we were on the excellent dual carriagewayAl where the main thought was that it is stupid these days to limit commercial vehicles to 40 mph on that class of road, As I have said it was difficult to hold the Beaver. back to 40

mph and most of the other goods traffic was passing us quite safely. On the part of Al with the more severe gradients—north of Leicester Forest—the average was 50 mph, and after this where MI is flatter the average increased to 55.6 mph for the whole way down to A4147 turn even though for most of this run there was heavy rain and a lot of traffic which kept getting in our way.

The criticisms that I have made from the driving angle could apply solely to the vehicle tested and in any case any driver would be quite happy to drive this Beaver. He has good working conditions in the Ergomatic cab, a fair degree of comfort. Visibility is very good indeed and I particularly appreciated the convex mirrors which gave an excellent view to the rear. With the mirrors now placed farther forward than originally not much rain or spray from the wheels gets on thern and in fact we did not have to clean the mirrors during the journey even though a lot of it was made in heavy rain or on wet roads.

In my time as passenger I did not find the left-hand side of the cab terribly comfortable. There is not a great deal of room and if it is desired to hold the arms at one's side, the right arm comes against a bonnet catch and the left arm against the door-opening lever. Consequently it is necessary to keep the arms half raised.

The Beaver has a high-output heating system but this was spoilt to some extent by the existence of draughts in the foot wellarea through gaps near the front of the engine cover on each side.

Basic price of the Beaver with turbocharged engine and semi-automatic gearbox as tested is £4,875.

Specification

Leyland Freightline Beaver ,i.urboehargeOliSearnfnell 30on-press iirt

MODEL

Freign-gire Beaver 8V69 32PTR Dft e'rn wheelbase. for,..vard-:":d,trol tractive unir witf• semi-a ..1tornatic transrmssion end Ercomatic all-steel t,g cab. and S.,:amme'l fanciers axle semi

tra tar 283 platform body.

MAKERS

Lev and Motors Ltd., Leyland Larcs and Scarnrnel: Lorries Ltd., Watford H

ENGINE

Leyland 690 turbocharged six cylinder direct-in

jection diesel engine bore 127mm stroke 146rnrn 15.75.n 1-, piston swept voLime. 11 1 litres (677.5 in.); compression ,at4o, 15_8 to 1: rnaxlmorn gross outri.,' 240 bhp i,BS AU 1411 at 2,200 rpm, max■inurn net torque 650 ib.ft. i85 AU la 1 a; 1.400

SETTINGS

10deg 81 0 C l.C.. 50deg A 8.0.0 ",

46cleg 8,3 fIC E.C., 14deg A T,D.C.: injection 26di,e, T.D C.. vah,....; c'earances, 0.020.r.: firing orde,„ 1.5.3 6 2 4.

TRANSMISSION

Thro,...gh 17 75m diameter fluid ■-,cepling wrth lock-up cl;.,tcn ro SSC ',.-;-soced epicyclic pea-box, with senli-a,..,torna tic control, thence 0Y onepiece p.opel.....1 st..art to the Leylano fully floating isoirsl-bcvtd and ht,b-eoicyir ci rear zxle

GEAR RATIOS

7.25, 5.58. 4.28, 3.29, 2 43. 1.87. 1.59, 1.22. 1 end 0.77 in 1 forward' reverse 5.97 and 4.6 to 1; rear axle ratio 6 06 to 1

BRAKE SYSTEM

Tractive unit: Westinghouse air-pressure system with Leyland 5 cam .eading-and trailing shoe units at both axles. Brake actuation by spring-brake chambers at all wheels. Combined secondary/park valve In cab exhausts Cr hordirg cVsprs,i,.:s. front units and pressurizes auxiliary 'i're to sonntraik.41for secondary system and astir sic a;r [spring sections at all vvheets for pnc. Lcao sensing valve in rear' axle air-pressure system.

Tnree-line air.pressure

S-cam leading-and.trailmg shoe brake both axles actuatect by double-diaphragm chEirnoe, Wheel-type perkIng brake semi-V'alie, mechanically to bogie brakes_

BRAKE DIMENSIONS

Diameter of drums, tract;ve unit front, i .

tractive unit rear, 15,5in , Serrt, trailer, 16 5 n : w-dth of linings, tractive unit front, t.-acfve unit rear, 7.0in., se vi-er, 7.0.. tracthie unit frictiow,i area 675 sq.in . semi ,-ai Cr frictional area, 908 spin., total frictional e es, 1,583 sq.in„ that is 53.1 sq.in. per ton weinnt as tested

FRAME

Ti,ctive Pressedi-steei c,css---iernbers bolted in position side-rn ernce,s asic mernbet:i wOcted 11 position.

STEERING

roar' recir;:ulatory ball

SUSPENSION

fruct;ve un?.: Serni•elliptic spnrajs vi:tth camoers er troot axle only,

rn -rue 'ip6r with b

radius rods.

ELECTRICAL

24 V coroperisated-vc17ag u,itro.: SYS:EMI.

I 10 .4h batteries.

TANK CAPACITY

483a