The Latest r Arab Pampers Passenger

Page 38

Page 39

Page 40

Page 41

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

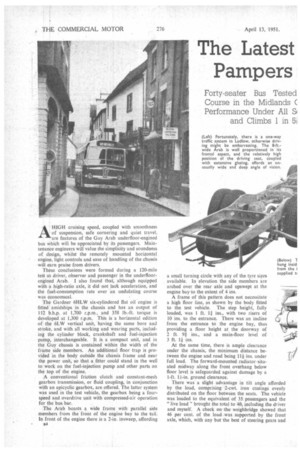

By L. J. COTTON, AHIGH cruising speed, coupled with smoothness of suspension, safe cornering and quiet travel. are features of the Guy Arab underfloor-engined bus which will be appreciated by its passengers. Maintenance engineers will value the simplicity and soundness of design, whilst the remotely mounted horizontal engine, light controls and ease of handling of the chassis will earn praise from drivers.

These conclusions were formed during a 120-mile test as driver, observer and passenger in the underfloorengined Arab. I also found that, although equipped with a high-ratio axle, it did not lack acceleration, and the fuel-consumption rate over an undulating course was economical.

The Gardner 6HLW six-cylindered flat oil engine is fitted amidships in the chassis and has an output of 112 b.h.p. at 1,700 r.p.m , and 358 lb.-ft. torque is developed at 1,300 r.p.m. This is a horizontal edition of the 6LW vertical unit, having the same bore and stroke, and with all working and wearing parts, including the cylinder block, crankshaft and fuel-injection pump, interchangeable. It is a compact unit, and in the Guy chassis is contained within the width of the frame side members. An additional floor trap is provided in the body outside the chassis frame and near the power unit, so that a fitter could stand in the well to work on the fuel-injection pump and other parts on the top of the engine.

A conventional friction clutch and constant-mesh gearbox transmission, or fluid coupling, in conjunction with an epicyche gearbox, are offered. The latter system was used in the test vehicle, the gearbox being a fourspeed and overdrive unit with compressed-air operation for the bus bar.

The Arab boasts a wide frame with parallel side members from the front of the engine bay to the tail. In front of the engine there is a 2-in. irtsweep, affording 84

a small turning circle with any of the tyre sizes supplied t(

available. In elevation the side members are arched over the rear axle and upswept at the engine bay to the extent of 4 ins.

A frame of this pattern does not necessitate a high floor line, as shown by the body fitted to the test vehicle. The step height, fully loaded, was 1 ft. U ins., with two risers of 10 ins, to the entrance. There was an incline from the entrance to the engine bay, thus providing a floor height at the doorway of

2 ft. 91 ins., and a main-floor level of 3 ft. 1k ins.

At the same time, there is ample clearance under the chassis, the minimum distance between the engine and road being ilk ins, under full load. The forward-mounted radiator situated midway along the front overhang below floor level is safeguarded against damage by a 1-ft. 11-in. ground clearance.

There was a slight advantage in tilt angle afforded by the load, comprising 2-cwt. iron castings evenly distributed on the floor between the seats. The vehicle

was loaded to the equivalent of 35'passengers and the " live load" brought the total to 40, including the driver and myself. A check on. the weighbridge showed that 46 per cent. of the load was supported by the front axle, which, with any but the best of steering gears and

geometry, would mean hard work for the driver in town. The Guy steering layout was well designed for the load, and I experienced no difficulty in manceuvring the Arab through Wolverhampton, which appeared particularly busy in the morning rush period of this important manufacturing centre.

With little experience of driving this vehicle, I found no difficulty in inching forward and stopping without discomfort to the passengers. The positive gear change, equal travel of the lever for all positions and the light pedal control afforded by air operation, are noteworthy details in the design.

Outside the town area, the Arab cruised comfortably at 45 m.p.h., and where conditions permitted 1 drove at higher speed, the steering at 50 m.p.h. being particularly light and accurate. These attributes have been noted in previous tests of goods and passenger models of Guy manufacture.

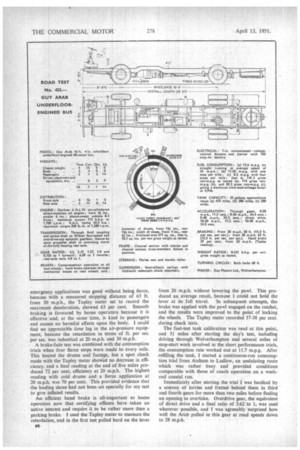

Acceleration and braking trials were made on the A5 road, which. although level in stretches for about two miles, carries heavy traffic and is relatively narrow. Starting from rest with second gear engaged and third gear selected, the Arab was quick off .the mark and reached 30 m.p.h. in 24.4 secs. after passing through the gears to direct drive. This is equal to the average acceleration rate of 32-seater single-decker chassis I have previously tested without bodies.

This acceleration trial was continued to 40 m.p.h.. the over-drive being brought into use at 36 m.p.h. The total time taken to reach the higher speed from rest was 50.3 secs. Engaging direct drive at crawling speed, the Arab again showed liveliness, despite the high-ratiofinal drive, and only 34.5 secs. were required to accelerate from 10-30 m.p.h.

Braking tests were made with the pedal switch connected to the Webley air pistol to mark theY road at the point of initial pressure. The retardation rate with n5 emergency applications was good without being fierce, because with a measured stopping distance of 65 ft. from 30 m.p.h., the Tapley meter set to record the maximum deceleration, showed 63 per cent. Smooth braking is favoured by home operators because it is effective and, at the same time, is kind to passengers and causes no harmful effects upon the body. I could find no appreciable time lag in the air-pressure equipment, because the retardation in terms of ft. per sec. per sec. was indentical at 20 m.p.h. and 30 m.p.h. A brake-fade test was combined with the consumption trials when four fierce stops were made to every mile. This heated the drums and facings, but a spot check made with the Tapley meter shovVed no decrease in efficiency, and a final reading at the end of five miles produced 72 per cent. efficiency at 20 m.p.h. The highest reading with cold drums and a fierce application at 20 m.p.h. was 70 per cent. This provided evidence that the leading shoes had not been set specially for my test to give inflated results.

An efficient hand brake is all-important to home operators now that certifying officers have taken an active interest and require it to be rather more than a parking brake. I used the Tapley meter to measure the retardation, and in the first test pulled hard on the lever from 20 m.p.h. without lowering the pawl. This produced an average result, because I could not hold the lever at its full travel, in subsequent attempts, the brake was applied with the pawl engaged on the ratchet, and the results were improved to the point of locking the wheels. The Tapley meter recorded 37-38 per cent. during check tests.

The fuel-test tank calibration was read at this point, and 31 miles after starting the day's test, including driving through Wolverhampton and several miles of stop-start work involved in the short performance trials, the consumption rate worked out at 11.7 m.p.g. After refilling the tank, I started a continuous-run consumption trial from Atcham to Ludlow, an undulating route which was rather busy and provided conditions comparable with those of coach operation on a weekend coastal run.

Immediately after starting the trial I was baulked by a convoy of lorries and fretted behind them in third and fourth gears for more than two miles before finding an opening to overtake. Overdrive gear, the equivalent of direct drive and a final ratio of 3.62 to I. was used wherever possible, and I was agreeably surprised how well the Arab pulled in this gear at road speeds down to 28 m.p.h. No attempt was made to sacrifice performance for economy of fuel consumption, which was proved by the high average speed for the trial-35 m.p.h. over a distance of 29.7 miles. I drove the bus in the manner known to drivers on excursion trips, but, even so, the consumption rate worked out at 13.6 m.p.g. Undoubtedly the Gardner HLW oil engine, coupled with appropriate transmission ratios, was responsible for the flexibility and economy, and there was no apparent loss of efficiency caused by the fluid coupling.

A test of steering and manceuvrability was provided in Ludlow, the turning point of the course, where the narrow streets with overhanging Tudor buildings demanded full attention ahead and overhead. Thanks to the good steering lock, all obstacles were avoided, and we made a circuit of the town without brushing the kerb.

From this point I enjoyed a period as a passenger, trying various seats to test the suspension and the noise of the engine below. First, I noticed that no attempt had been made to reduce overall height, the headroom of the 40-seater saloon being 6 ft. 71 ins, at its lowest point, so that there was no need to stoop when walking the length of the gangway. There was a wheel-arch intrusion over. the rear axle, but• this would be insufficient to cause discomfort to the passenger sitting immediately behind the wheel box.

With full load, the suspension is flexible, and the effects of severe bumps on the road are stnoothed by NeWton telescopic shock absorbers. Most of the engine noise is carried away below

the body, and a layer of Burgess acoustic material below the floor is sufficient to absorb practically all the characteristic cackle of the oil engine at full load.

At Bridgnorth the consumption rate was again checked, This part of the trial had included the circuit of Ludlow and town work in Burwarton, a total of 231 miles, covered at an average speed of 33 m.p.h. and a fuel-consumption rate of 12.95 m.p.g.

Two Stop-start Tests

Two trials were made on Hermitage Hill, a mile-long gradient averaging 1 in 12, the. first with a stop-start test, where the Tapley gradient meter registered 1 in 8/. As this was accomplished with ease in low gear, 1 ambitiously called for a second attempt, employing the next ratio, but this was too much

During the repeat climb I took temperatures; the radiator top tank recording 142 degrees F. at the start, with an ambient reading of 46 degrees. The two lowest ratios were used for the trial, which occupied 2 mins. 39 secs. and caused the water temperature to rise 121 degrees F. It is understood that the radiator fitted was a prototype unit and that subsequent production models have. improved cooling arrangements, so that the same radiator is adequate "for home and

overseas requirements. • .

From the fop of. Hermitage Hill the road back to the works was hilly,, and a detour was made to my -favourite test climb at Tettenhall. A sharp turn off the main road to the start of Old Hill prevents the use of rush tactics, and the short and steep gradient has to be tackled in a low ratio. A rapid change was made to bottom gear and the Arab climbed easily to the peak, veering to the off side of the road to take in the 1-in-51 section. Where such gradients are encountered in normal bus operation, probably involving moving away from rest with full load on a 1-in-6 incline, it would be preferable to employ the axle ratio of 5.6 to 1.

11.6 m.p.g. for 108 miles On returning to the works we prepared the fuel system for the service-bus consumption trials. Incidentally, the consumption rate over the 108-mile circuit, including performance and hill-climbing tests, worked out to 11.6 m.p.g. The inter-urban trial, represented by one stop per mile, was made on an estate where there were numerous turns. The " accumulative " stop-watch was used to measure actual running time. This was calculated independently to exclude the 15-sec. stops.

Starting and finishing at the same point on the five-mile circuit, incorporating two reverse turns, the average speed was 24 m.p.h. and the fuel-consumption rate was 11.05 m.p.g. There was full scope for using overdrive under these conditions, but for local bus service, with four stops per mile, the direct-drive-top gearbox could be more advantageously employed.

On the second circuit, with four stops per mile, fuel was used at the rate of 8.2 mpg. Both trials proved the economy of the Arab, and I think that, with the lower-ratio final-drive unit fitted, there might have been a further gain in the local service run.

Running temperatures were taken at the conclusion of these tests, and following the usual trend of underfloorengined models, the lubricating-oil temperature was low (108 degrees F.). With the underfloor engine, which is less shielded than the conventional forward-mounted vertical unit, it is not difficult to keep running temperatures low. Indeed, some overseas operators find it necessary to screen the underfloor power unit to keep operating temperatures at a reasonably efficient working level.

The frequent use of the gearbox, making 16 changes to every mile, had caused a slight warming-up, but 170 degrees F. can hardly be regarded as above average for a short-stage test. The axle temperature of 145 degrees F. showed that the worm gear was well bedded down and relatively little efficiency was lost in transmission.