Bedford VAL and VAM/Dupli

Page 62

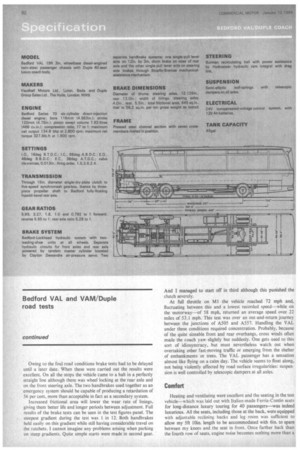

Page 63

Page 64

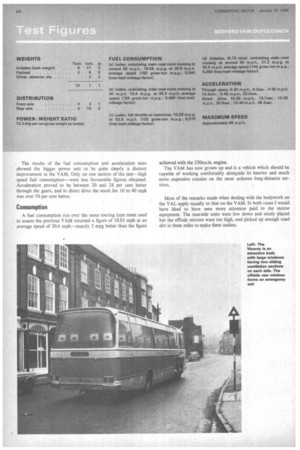

Page 65

Page 66

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

:oaches

WEN VAUXHALL MOTORS introduced the KM range of u-Tucks early in 1967, the new Series 70 diesel engine also made its debut. It was a natural development for this power unit to be fitted in the company's two heaviest passenger chassis. The smaller chassis, the 'YAM with the Bedford 330cu.in. diesel, was underpowered for serious high speed long-distance work, while the larger, the VAL, still employed a power unit made by a competitor. COMMERCIAL MOTOR has now carried out a full road test of the VAL, and a supplementary test of the YAM both fitted with the Series 70 466cu. in. engine and with bodywork by Duple.

My major criticism is that in both cases more could have been done by the coachbuilders to deaden engine noise—the vehicles had Duple Viceroy bodywork. The noise level was high. Passengers, particularly those in the first three or four rows, would not like it.

Insulation

During the VAL test an injector pipe fractured, and smoke and fumes poured through numerous gaps in the engine surround during the remainder of the test. A graphic example of the lack of complete insulation! However, the din was not solely caused by noise entering through these holes. A sounding-stick placed upon the dash assembly at any point showed this to act as a sounding box, amplifying engine noise considerably. The Series 70 engine is rather on the noisy side, but on both the vehicles tested on this occasion there was, in my opinion, insufficient insulation.

Road conditions during the test were about the dirtiest I can remember. Screens, light glasses and rear windows remained transparent for only a few minutes. Screen washing and wiping equipment came in for a most severe test and they did not acquit themselves at all well. The washers—despite adjustment—could not be directed to get water on to the screen at the correct places and the wiped area was so badly situated that high speed driving on Ml proved to be extremely tiring. A blind spot almost 2ft wide developed on the offside corner of the screen during the high-speed run over 22 miles of motorway.

I feel that if the stylists of the coachbuilding world insist on curved windscreens then they must make determined efforts to offer drivers a clear field of vision during night-runs and dirty conditions.

Another complaint I have about the bodywork was the vast array of identical switches in both vehicles. They were low down on the dash and to say the least this did not make for easy identification in the dark. It is no use saying that a driver will get used to the layout. What about the occasions when a spare driver will take over?

Accessibility

I suppose most coach drivers carry a small pair of steps in a luggage compartment. Nevertheless, some provision should be made to allow them to climb up and clean front and rear screens. A flat top to the bumpers and a couple of grab handles is all that is needed to make a great contribution to safety.

One last point. When will designers realize that professional drivers are dazzled by bright sunlight just the same as are private car drivers. While adequate sun visors are supplied in almost every modern car, many coaches are still fitted with an apology for a visor—usually too small to be effective with today's fashionable deep windows. And we must remember that the sun shines through side windows as well.

Handling

Results achieved with the VAL were little different to those recorded when the model was first tested by COMMERCIAL MOTOR in 1963. But my reactions when driving this particular vehicle were that it seemed considerably more lively than any of the other half dozen VALs that I have handled. It did not need so much "driving" as the earlier version. Much less effort was needed to get the machine moving and its top gear capabilities had to be sampled before they were fully appreciated. Whereas the previous test vehicle recorded a maximum speed of only 58 mph the latest version with the same final-drive ratio showed a maximum of 72 mph. The capability of the VAL to cruise at 60-65 mph with little fall-off on motorway gradients makes it ideal for long-dittance services.

The gearchange and throttle pedal tended to be a bit on the heavy side but every other control used while in motion was delightfully lightly loaded. I say "while in motion" for the main handbrake was extremely heavy to operate. Steering, with hydraulic ram power assistance, was if anything a bit too light and could easily land one in trouble if treated carelessly. For manoeuvring in tightly packed car-parks, the VAL's steering was perfect.

At the time of its introduction much emphasis was placed on safety factors offered by the VAL design. There is less chance of running out of road if a tyre on a steering axle bursts. The design has three separate braking systems with the service brake having a split circuit and the latest model greater brake drum area giving better fade resistance.

The vehicle handled more easily than a machine half its size, and this must give drivers the ability to manage it for long periods without tiring. This I believe, is the criterion regarding vehicle safety. There remains of course, the noise factor mentioned which can detract from driving efficiency.

When carrying out the simulated touring run over 15.2 miles between the MI /A5 junction and Woburn Sands, the behaviour of the VAL was impeccable. Although my route through busy Dunstable had numerous traffic signals and pedestrian crossings, and while on the open road I restricted speed to a 33 mph maximum, an average speed of 29.4 mph was recorded. Fuel consumption on this run was a little disappointing at 15.9 mpg.

Payload

A similar run with the Leyland-engined version at 30.5 mph had produced 16 mpg although the latest version was just on 12cwt heavier, now having a maximum permissible g.v.w. of 24,6001b, the extra payload being made up by passengers' luggage. Owing to the foul road conditions brake tests had to be delayed until a later date. When these were carried out the results were excellent. On all the stops the vehicle came to a halt in a perfectly straight line although there was wheel locking at the rear axle and on the front steering axle. The two handbrakes used together as an emergency system should be capable of producing a retardation of 56 per cent, more than acceptable in fact as a secondary system.

Increased frictional area will lower the wear rate of linings, giving them better life and longer periods between adjustment. Full results of the brake tests can be seen in the test figures panel. The steepest gradient during the test was 1 in 12. Both handbrakes held easily on this gradient while still having considerable travel on the ratchets. I cannot imagine any problems arising when parking on steep gradients. Quite simple starts were made in second gear. And I managed to start off in third although this punished the clutch severely.

At full throttle on MI the vehicle reached 72 mph and, fluctuating between this and a lowest recorded speed while on the motorway—of 58 mph, returned an average speed over 22 miles of 53.1 mph. This test was over an out-and-return journey between the junctions of A505 and A557. Handling the VAL under these conditions required concentration. Probably, because of the quite sizeable front and rear overhangs, cross winds often made the coach yaw slightly but suddenly. One gets used to this sort of idiosyncracy, but must nevertheless watch out when overtaking other fast-moving traffic or emerging from the shelter of embankments or trees. The VAL passenger has a sensation almost like flying on a calm day. The vehicle seems to float along, not being violently affected by road surface irregularities: suspension is well controlled by telescopic dampers at all axles.

Comfort Heating and ventilating were excellent and the seating in the test vehicle—which was laid out with Italian-made Ferria-Contin seats for long-distance luxury touring for 40 passengers—was indeed huturious. All the seats, including those at the back, were equipped with adjustable reclining backs and leg room was sufficient to allow my 5ft 10in, length to be accommodated with 6in. to spare between my knees and the seat in front. Once farther back than the fourth row of seats, engine noise becomes nothing more than a

not-too-disturbing drone, although when climbing a gradient in low gear it filtered almost to the rear seats quite loudly.

The unladen ride was as good as the laden. And as it is in the unladen condition that most of the damage to bodywork is done, it seems fair to say that the VAL bodywork should last for a long time before developing squeaks and rattles.

As tested, the VAL Viceroy 36 costs: chassis £1,910; body £4,459; a total of £6,369.

VAM consumption and performance

The VAM was subjected to a test which would furnish only the results of the new installation because the chassis was otherwise unchanged from that previously tested (CM December 12, 1965). The results of the fuel consumption and acceleration tests showed the bigger power unit to be quite clearly a distinct improvement in the YAM. Only on one section of the test—high speed fuel consumption—were less favourable figures obtained. Acceleration proved to be between 20 and 28 per cent better through the gears, and in direct drive the result for 10 to 40 mph was over 50 per cent better.

Consumption A fuel consumption run over the same touring type route used to assess the previous VAM returned a figure of 18.05 mph at an average speed of 30.6 mph—exactly 2 mpg better than the figure achieved with the 330cu.in. engine.

The VAM has now grown up and is a vehicle which should be capable of working comfortably alongside its heavier and much more expensive cousins on the most arduous long-distance services.

Most of the remarks made when dealing with the bodywork on the VAL apply equally to that on the VAM. In both cases I would have liked to have seen more attention paid to the mirror equipment. The nearside units were low down and nicely placed but the offside mirrors were too high, and picked up enough road dirt in three miles to make them useless.