Charred reputation

Page 46

Page 47

Page 48

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

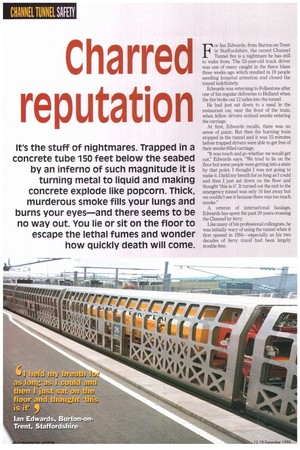

It's the stuff of nightmares. Trapped in a concrete tube 150 feet below the seabed by an inferno of such magnitude it is turning metal to liquid and making concrete explode like popcorn. Thick, murderous smoke fills your lungs and burns your eyes—and there seems to be no way out. You lie or sit on the floor to escape the lethal fumes and wonder how quickly death will come.

For Ian Edwards, from Burton-on-Trent in Staffordshire, the recent Channel Tunnel fire is a nightmare he has still to wake from. The 53-year-old truck driver was one of many caught in the fierce blaze three weeks ago which resulted in 19 people needing hospital attention and closed the tunnel indefinitely.

Edwards was returning to Folkestone after one of his regular deliveries to Holland when the fire broke out 12 miles into the tunnel, He had just sat down to a meal in the restaurant car, near the front of the train, when fellow drivers noticed smoke entering the carriage.

At first, Edwards recalls, there was no sense of panic. But then the burning train stopped in the tunnel and it was 15 minutes before trapped drivers were able to get free of their smoke-filled carriage.

"It was touch and go whether we would get out," Edwards says. "We tried to lie on the floor but some people were getting into a state by that point. I thought! was not going to make it. I held my breath for as long as! could and then I just sat down on the floor and thought 'this is it'. It turned out the exit to the emergency tunnel was only 10 feet away but we couldn't see it because there was too much smoke."

A veteran of international haulage, Edwards has spent the past 20 years crossing the Channel by ferry Like many of his professional colleagues, he was initially wary of using the tunnel when it first opened in 1994—especially as his two decades of ferry travel had been largely trouble-free. But as cut-throat competition from Eurotunnel enticed more and more hauliers away from the traditional routes, drivers like Edwards were forced to forget their reservations and venture under, rather than over, the Channel.

Diggings for the world's longest undersea tunnel first began over 100 years ago but were abandoned on several occasions, largely because of financial or technical obstacles.

But safety too has always been a major hurdle. To overcome this, rough standards were imposed on the tunnel's construction to ensure that the risks were minimised (the tunnel, it is said, is built to withstand an earthquake) and comprehensive procedures set in place to cope with all emergencies.

Serious breakdown

Initial evidence suggests a serious breakdown in those procedures. Investigators are analysing why the train failed to carry on to Folkestone and the driver did not decouple the burning carriage—two actions clearly laid out in emergency procedures. They are also looking closely at the controversial "lattice-work" design of the semi open-sided carriages used to carry heavy goods vehicles, thought by some experts to be a key factor in the fire's rapid progress.

As early as 1987 safety experts were warning the design was dangerous. Eurotunnel, which favoured the wagons because they were lighter and therefore cheaper to run, was ordered by the Channel Tunnel Safety Authority to phase them out by March 1994.

But after intensive lobbying, the authority backed down and granted Eurotunnel a full operating certificate. The question facing the authority now is should the design be allowed back into service when the tunnel reopens— pending a final judgement on the wagons' safety.

Eurotunnel says it is committed to the design and has ordered an extra 72 wagons to be delivered in just over a year's time. But according to tunnelling engineer John Whitwell, deputy secretary of the Institution of Civil Engineers, some modifications will have to be made.

"They will have to do something to modify the wagons," he says. "This could happen again and it's sod's law it will. My feeling is they will have to look at it extremely carefully because if you have a fire which actually closes the tunnel down then the viability of the whole project goes out the window." Stop-gap measures, Whitwell says, could include lightweight fireproof systems that could be put in the wagons without dramatically increasing weight—and therefore cost— or the use of fire control mats that would automatically smother the flames before they spread.

His own verdict is that the disaster was the result of a breakdown in performance. "Designed into the tunnel are as many safety measures as there could be. But in the end it did not work."

In the wake of the fire, hauliers will be anxious in case the perceived increase in risk will have a knock-on effect on insurance rates, both for vehicles and goods-in-transit.

Premiums already represent a major drain on cash flow for many operators. For some, any further increase could be crippling.

Potential claim

A spokesman for the Lloyds insurance syndicate Crowes, which specialises in cover for haulage vehicles, says the fire has highlighted a potential claim which "could be enormous" if the liability is found to lie with the owner of a heavy goods vehicle.

"If the insured can be held largely liable then there could be an extremely big claim for losses," he warns.

Underwriters are looking closely at what claims might run to: at worst it could run to millions of pounds.

Insurers say tough competition is helping to keep the lid on premiums. But it is doubtful that rates for vehicle insurance could withstand a multi-million-pound claim for losses.

Eurotunnel itself is covered by insurance for damage and consequential loss but this episode will do little to improve its tarnished financial image. Dogged by massive debts, it now faces two further blows from loss of revenue and a substantial claim for negligence from the French and British truck drivers who were caught in the fire. "All the time it's out of action the tunnel has got no money coming in," says John Chapman, operations director of the Road Haulage Association and a former Eurotunnel employee.

Yet the freight industry, Chapman notes, is keen to see the tunnel back in full action as soon as possible. It has fed ravenously off the price war of the past two years and is anxious that the competition between Eurotunnel and its sea-bound rivals should continue.

"The freight industry seems to be saying get back in business as soon as possible," says Chapman. "Rates have come down very significantly and as far as RBA members are concerned it's been like Christmas every day. Whatever happens to the financial position of the tunnel it will still be there; it is not going to go away. And it works. Delays are few and far between and the mechanics are very sound."

But it is certain to lose at least one one regular customer. Ian Edwards has vowed never to venture into the tunnel again unless Eurotunnel agrees to fit oxygen masks for each seat on the train and sprinklers to douse any flames.

"I keep having bad headaches and getting bloodshot eyes," he says. "Also, I feel anxious and nervous. I've used the tunnel a couple of hundred times but I won't ever use it again." fl by Pat Hagan