Would a National Clearii iouse Solve To-day's Road -transport Problems?

Page 36

Page 37

Page 38

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

OFTEN enough in the past the voices of the industry's leaders have asked " What is the future of road transport? " In time of war, however, it is not unnatural that those who speak or 1 Lislate for the industry should do so on the basis of the necessity of the moment, rather than on the problematical future. Therefore, to many, the reply " It's the war" will be sufficient answer to complaints regarding the circumstances in which operators find themselves to-day. But is it really?

If a haulier be without petrol to carry his normal traffic from, say. Manchester to London, then we are told it can be put on rail and the transport owner can play his little part in railhead distribution. All kinds of re-arrangements are proposed, but few of them can give comfort to the operator who sees the work of many years being dissipated at one blow and, not unnaturally, wonders whether, after a successful outcome of the war, the railways will be willing to hand him back whatever remnants remain of his connection.

Road Transport Saves Industry.

Even if the future outlook be completely satisfactory, there would still be little justification for a complacent State of mind when the trader has to accept inefficient conditions of transport, with goods being despatched to disappear into the blue, then to be delivered, perhaps, 200 miles away a fortnight later. Road transport rescued industry from this state years ago and there seems no reason why it should not do so again.

At the moment we have the spectacle of a carrier in Boltdn with an urgent load for Glasgow being unable to carry it there as his remaining petrol ration will not enable him to complete the return trip. Meanwhile, in Glasgow there is another carrier with an urgent load for, say, Manchester who is unable to bring it south because he can afford sufficient petrol for only the outward journey. Surely we can do better than this!

At the time of the 1914-1918 war road transport was made up predorninently of local services, but it became apparent to both business men and certain authorities that to utilize 5,26 able facilities efficiently the vehicles should be fully loaded for the greatest possible part of their running time.

A notable development of this situation took place in the summer of 1917, when the Manchester Chamber cf Commerce opened a road-transport interchange department. The object was to bring together the owners of motor vehicles requiring return loads and concerns having such traffic available, so as to facilitate deliveries by the most economical means, thus effecting savings in labour and petrol.

Prior to this time any organized clearing-house system had been absent, although there had been certain transport agency work of a rather different nature. In fact, immediately before the establishment of the Manchester scheme some work of a similar kind had been commenced in Birmingham.

The Manchester scheme was intended to apply 'within a radius of 30-40 miles, a qualification that gives some indication of the road-transport position at that period. Now, however, industry has come to rely on road motors to carry all classes of goods throughout the length and breadth of the country. When we interviewed Mr. Nathan Fine, manager of that original Manchester scheme and more recently managing director of probably the hest-known clearing house in the country, he suggested that many cliffi• culties could be solved by an official national clearg house with branches in all the principal towns.

Value of the Clearing House.

. Taking our previous example of the goods urgently needed to be conveyed from Bolton to Glasgow, the trader, in this case, would telephone his local clearing-house representative who would be able to ascertain from his records whether any Glasgow operator was returning from the Bolton district. If such an operator had sufficient space he would take the load.

However, if no Scottish vehicle were available, the local operator on the particular route would he given instructions to convey the goods and, the petrol authorities working in liaison with the clearing house, the operator would be provided with the necessary fuel tickets for the return journey. Due intimation would be made to Glasgow and the vehicle would be available to carry the next load to Lancashire.

Clearly, by the proper development of such a system under experienced management, sufficient savings in Wel and labour could be accomplished to ease the restrictions that are already making themselves felt to the detriment of home and export business. At the same time, operators who so desired could maintain such of their present activities as could be continued -with out wastage. .

Should a national scheme fail to materialize there will, obviously, lie greater scope for the private clearing house that can work efficiently, for there is still much light running. To be of value to the nation, however, the private agent must offer real facilities for the systematic linking-up of such road transport as may be available.

No Room for the Bucket-shop.

The fee-snatching bucket-shop must never be permitted to arise again, and carriers who may now find the need tor co-operation with clearing houses should take every possible step to ascertain that they work only with the reputable type, which is most anxious to put down harmful practices.

Even in the beginning the Manchester scheme—hall-marked, as it was—had to face serious criticism from hauliers, who regarded the plan as an encroachment on their preserves. Quickly they came to see, however, that, properly handled, it would give them real help in continuing to run services at rates which could be borne by industry. Outside the matter of competition, a typical question was whether the savings justified the establishment of such an enterprise.

To the hauliers of those days it seemed impossible for the plan to be run without inflicting loss of trade in general, and local operations, in

particular, looked for an assurance that there would be a reversion to the old conditions at the conclusion of hostilities. However, as the scheme was backed by the Manchester Chamber of Commerce, it pointed to the fact that it was desio°neci to deal with a manifest want; the Chamber's object was, and is, to assist industry and not to make profits.

By the spring of 1918 some 350 lorries had been entered on the register and an average of 400 tons per week was being moved simply by utilizing vehicles that normally would have been running light. From the start, in July, 1917, until the end of the year the total tonnage carried was 2,225, whilst from January to August, 1918, the figure was 11,632, and with this increase in traffic the system had become self-supporting ; for the whole of the year 1918 the total was 23,766 tons. A great bulk of the carrying was done within a radius of 50 miles from Manchester, but operations also extended so far as London.

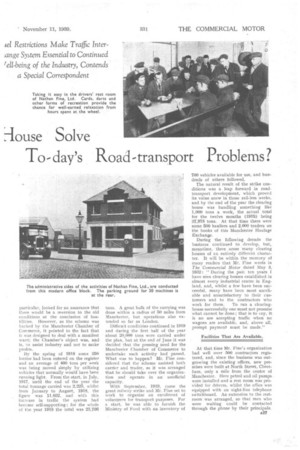

Difficult conditions continued in 1919 and during the first half of the year about 20,000 tons were carried under the plan, but at the end of June-it was decided that the pressing need for the Manchester Chamber of Commerce to undertake such activity had passed. What was to happen? Mr. Fine considered that the scheme assisted both carrier and trader, so it was arranged that he should take over the organization and operate in an unofficial capacity.

With September, 1919, came the great railway strike and Mr. Fine set to work to organize an enrolment of volunteers for transport purposes. For a start, he was able to furnish the Ministry of Food with an inventory of 700 vehicles available for use, and hundreds of others followed.

The natural result of the strike conditions was a leap forward in roadtransport development, which proved its value anew in those rail-less weeks, and by the end of the year the clearing house was handling something like 1,000 tons a week, the actual total for the twelve months (1919) being 37,978 tons. At that time there were some 500 hauliers and 2,000 traders on the books of this Manchester Haulage Exchange.

During the following decade the business continued to develop, but, meantime, there arose many clearing houses of an entirely different character. It will be within the memory of many readers that Mr. Fine wrote in The Commercial Motor dated May 3, 1932: _" During the paAt ten years I have seen clearing houses established in almost every industrial centre in England, and, whilst a few have been successful, many have been most unreliable and unsatisfactory to their customers and to the contractors who

work for them. To run a clearinghouse successfully one must not promise what cannot be done ; that is to say, it is no use accepting traffic when no wagons are available, and, above all, prompt payment must be made."

Facilities That Are Available.

At thattime Mr. Fine's organization had well over 500 contractors registered, and, since the business was outgrowing the existing offices, new premises were built at North Street, Cheetham, only a mile from the centre of Manchester. Here petrol and oil pumps. were installed and a rest room was pro-. vided for drivers, whilst the office was equipped with an eight-line telephone switchboard. An extension to the restroom was arranged, so that men who were waiting could be contacted through the phone by their principals. Behind the modern administrative block an extensive vehicle park, with accommodation for 50 machines, was provided.

Since their institution, rather over seven years ago, these facilities have been used and enjoyed by transport workers from every part of the country.

It has been the habit of Mr. Fine personally to visit every customer, and his journeys have taken him as far afield as Glasgow and Southampton. Apart from the importance of the business contacts thus maintained, his intimate knowledge of the situation of the various establishments has meant that no driver need depart from the office without precise instructions as to the whereabouts of the customer.

Whereas in the earliest days of clearing-houses, it was necessary for the agent to convert both contractor and customer from their old ways of thinking, now it is difficult to convince the trader that fuel rationing is so severe as to prevent road deliveries over long distances.

A man who is still in the position of being able to manufacture or sell normally is demanding that, somehow, transport shall be provided to satisfy his requirements. What will be the ultimate result remains to be seen, but it is certain that the clearing house can once again ease and expedite the flow of traffic.

In 1917, for all effective purposes, road transport was confined to a limited radius and it was natural that some form of local guidance should be evolved. One wonders whether the present situation will result in the establishment of traffic interchange on a national basis with the active cooperation of the fuel authorities. Or will there be an extension of private enterprise? Be that as it may, the industry—especially the sectionwhich previously has been out of touch with the clearing-house—will look for an enlightened policy in any developments that take place.

Apart from all else, a clearing-house should be a guarantor, first, to see that the customer obtains the best that road transport can offer, and, secondly, to see that the operator is promptly and properly rewarded. Subject to those conditions, the system may well have an immensely and increasingly important part to play in the days that are to come.