Austin Gipsy .

Page 64

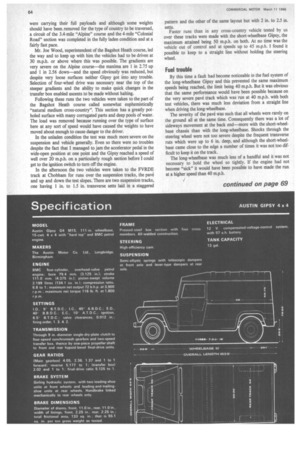

Page 65

Page 66

Page 71

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

4x4

X TEHIC LES such as the Austin Gipsy are an indispensable part V of the transport used in agriculture, on construction sites and the like. More than any other vehicle they have to perform well for the two basically different parts of their dual life—able to get across the roughest country and, at the same time, be comfortable and as easy to drive as a passenger car when on made-up roads.

It is certain that the small, dual-purpose 4 X 4 models have to be tough to stand up to the sort of treatment they will get, and in a road test the only way to obtain a good assessment of the vehicle's capability is to find the roughest possible test circuit.

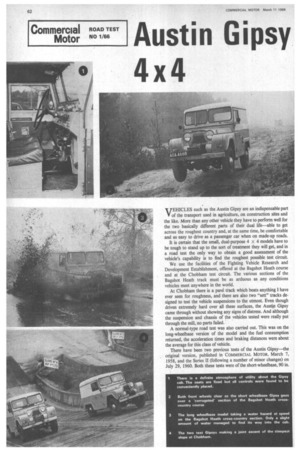

We use the facilities of the Fighting Vehicle Research and Development Establishment, offered at the Bagshot Heath course and at the Chobham test circuit. The various sections of the Bagshot Heath track must be as arduous as any conditions vehicles meet anywhere in the world.

At Chobham there is a pave track which beats anything I have ever seen for roughness, and there are also two "sett" tracks designed to test the vehicle suspensions to the utmost. Even though driven extremely hard over all these surfaces, the Austin Gipsy came through without showing any signs of distress. And although the suspension and chassis of the vehicles tested were really put through the mill, no parts failed.

A normal-type road test was also carried out. This was on the long-wheelbase version of the model and the fuel consumption returned, the acceleration times and braking distances were about the average for this class of vehicle.

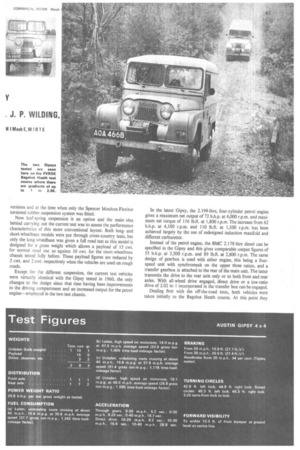

There have been two previous tests of the Austin Gipsy—the original version, published in COMMERCIAL MOTOR, March 7. 1958, and the Series II (following a number of minor changes) on July 29, 1960. Both these tests were of the short-wheelbase, 90 in. versions and at the time when only the Spencer Moulton Flex itor torsional rubber suspension system was fitted.

Now leaf-spring suspension is an option and the main idea behind carrying out the current test was to assess the performance characteristics of this more conventional layout. Both longand short-wheelbase models were put through cross-country tests. but only the long-wheelbase was given a full road test as this model is designed for a gross weight which allows a payload of 15 cwt. for normal road use as against 10 cwt, for the short-wheelbase chassis tested fully before. These payload figures are reduced by 3 cwt. and 2 cwt. respectively when the vehicles are used on rough roads.

Except for the different suspension, the current test vehicles were virtually identical with the Gipsy tested in 1960, the only changes to the design since that time having been improvements to the driving compartment and an increased output for the petrol engine-employed in the two test chassis. In the latest Gipsy, the 2.199-litre, four-cylinder petrol engine gives a maximum net output of 72 b.h.p. at 4,000 r.p.m. and maximum net torque of 116 lb.ft. at 1,800 r.p.m. The increase from 62 b.h.p. at 4,100 r.p.m. and 110 lb.ft. at 1,500 r.p.m. has been achieved largely by the use of redesigned induction manifold and different carburetter.

Instead of the petrol engine, the BMC 2.178-litre diesel can be specified in the Gipsy and this gives comparable output figures of 55 b.h.p. at 3,500 r.p.m. and 89 lb.ft. at 2,800 r.p.m. The same design of gearbox is used with either engine, this being a fourspeed unit with synchromesh on the upper three ratios, and a transfer gearbox is attached to the rear of the main unit. The latter transmits the drive to the rear axle only or to both front and rear axles. With all-wheel drive engaged, direct drive or a low-ratio drive of 2.02 to I incorporated in the transfer box can be engaged.

Dealing first with the off-the-road tests, both vehicles were taken initially to the Bagshot Heath course. At this point they were carrying their full payloads and although some weights should have been. removed for the type of country to be traversed, a circuit of the 3.4-mile "Alpine" course and the 4-mile "Colonial Road" section was completed in the fully laden condition and at a fairly fast pace.

Mr. Joe Wood, superintendent of the Bagshot Heath course, led the way and to keep up with him the vehicles had to be driven at 30 m.p.h. or above where this was possible. The gradients are very severe on the Alpine course—the maxima are I in 2.75 up and 1 in 2.56 down—and the speed obviously was reduced, but despite very loose surfaces neither Gipsy got into any trouble. Selection of four-wheel drive was necessary near the top of the steeper gradients and the ability to make quick changes in the transfer box enabled ascents to be made without halting.

Following these runs the two vehicles were taken to the part of the Bagshot Heath course called somewhat euphemistically "natural medium cross-country". This section has a greatly potholed surface with many corrugated parts and deep pools of water. The load was removed because running over the type of surface here at any sort of speed would have caused the weights to have moved about enough to cause danger to the driver.

In the unladen condition the test was much more severe on the suspension and vehicle generally. Even so there were no troubles despite the fact that I managed to jam the accelerator pedal in the wide-open position at one point and the Gipsy reached a speed of well over 20 m.p.h. on a particularly rough section before I could get to the ignition switch to turn off the engine.

In the afternoon the two vehicles were taken to the FVRDE track at Chobham for runs over the suspension tracks, the pave and up and down the test slopes. There are two suspension tracks, one having 1 in. to 1.5 in. transverse setts laid in a staggered pattern and the other of the same layout but with 2 in. to 2.5 in. setts.

Faster runs than in any cross-country vehicle tested by us over these tracks were made with the short-wheelbase Gipsy, the maximum attained being 50 m.p.h. on both. At no time was the vehicle out of control and at speeds up to 45 m.p.h. I found it possible to keep to a straight line without holding the steering wheel.

Fuel trouble By this time a fault had become noticeable in the fuel system of the long-wheelbase Gipsy and this prevented the same maximum speeds being reached, the limit being 40 m.p.h. But it was obvious that the same performance would have been possible because on the very severe pave track which was run at 40 m.p.h. with both test vehicles, there was much less deviation from a straight line when driving the long-wheelbase.

The severity of the pave Was such that all wheels were rarely on the ground all at the same time. Consequently there was a lot of sideways movement at the back end—more with the short-wheelbase chassis than with the long-wheelbase. Shocks through the steering wheel were not too severe despite the frequent transverse ruts which were up to 6 in. deep, and although the short-wheelbase came close to the edge a number of times it was not too difficult to keep it on the track.

The long-wheelbase was much less of a handful and it was not necessary to hold the wheel so tightly. If the engine had not become "sick" it would have been possible to have made the run at a higher speed than 40 m.p.h. Because of the severity of the sett tracks and pave some of the load had been removed before these tests, but this was all put back for the hill-climbing tests on the FVRDE slopes. The handbrakes held both test vehicles when facing up and down the 1 in 4 slope, but the 1 in 3 was just too much for this unit on the short-wheelbase chassis, whilst on the long-wheelbase it would only hold the vehicle stationary when facing down the slope.

Restarts in first-high were possible when facing up the 1 in 4 slope and in first-low up the 1 in 3. Reverse-high restarts when facing down were found to be within the capability of both Gipsy's on these two inclines.

No restart tests were attempted on the steeper FVRDE slopes, which have gradients of 1 in 2 and 1 in 1.73, because the handbrakes would not have held the vehicles. But easy ascents of these two inclines were made with first-low gear engaged in both cases. There was some concern near the top of the 1 in 1.73 with the long-wheelbase model, the fault in the fuel system causing the engine almost to cut out at one point, but the vehicle just managed to keep going long enough to get over the final few yards or so.

Taken all round, both vehicles put up a very creditable performance on the Bagshot Heath and Chobham tests and the longwheelbase chassis also acquitted itself very well on the normaltype road test. It will be seen from the specification table that the gross weight for this was 2 tons 8.75 cwt. This was 1.25 cwt, above the design figure, but almost what it should have been if a diesel engine had been fitted in the model. All the tests were carried out at this weight, fuel consumption, brakes and acceleration in the Luton area and hill climbing at Bison Hill, Dunstable.

Fuel consumption figures were quite a bit worse than those obtained with the Series II Gipsy tested in 1960, but comparable with the results on the original design obtained in 1958. This points to the figures for the Series II being a little unrepresentative for the model, and for normal day-to-day running about I would expect to obtain a fuel consumption of around 17 to 19 m.p.g. Whilst this may appear heavy for a vehicle designed for a payload of 15 c wt . , it must be remembered that there has to be some penalty if the performance as demonstrated at the FVRDE track is to be obtained.

Good low-speed traction

A measure of the performance is also shown by the times obtained on the acceleration tests. These were very good indeed and little different from the results on the previous tests in spite of the increase in gross weight. There was a good pull-away in the direct drive tests, the engine proving tractable at speeds as low as 8 m.p.h. Braking performance was excellent and the stopping distances obtained represent an improvement of about 18 per cent over the previous models tested.

There was rear-wheel locking on all the maximum-pressure stops and from both 20 and 30 m.p.h. Tapley-meter readings for maximum deceleration of 95 per cent were obtained. The handbrake efficiency of 34 per cent confirmed the findings on the 1 in 3 test slope at Bagshot.

Hill-climbing performance was assessed on a maximum power ascent of Bison, which has an average gradient of 1 in 10.5 and a maximum of 1 in 6.5 in its 0.75-mile length. From a standing start at the bottom the climb was made in the good time of 1 min. 57 sec. Second gear was the lowest needed—it was engaged for 32 sec.—and the minimum speed on the ascent was 23 m.p.h. Little increase in engine coolant temperature was noticeable on the dashmounted temperature gauge; this point could not be checked accurately as the thermometer being used broke during the test.

Turning round at the top of Bison, brake fade was checked on a run down the hill in neutral with the brakes in use to restrict the speed to 20 m.p.h. For the last section, where the gradient is slight, top gear, was engaged and full throttle applied with the brakes still on to keep to 20 m.p.h. At the bottom, after a run lasting 2 min. 25 sec., with 34 sec. spent driving against the brakes, a maximum pressure stop from 20 m.p.h. produced a Tapley-meter reading of 57 per cent. Although this was a big reduction compared with the cold-drum tests the figure is high enough for it to be assumed that there should be no real problem with brake fade on the Gipsy design.

Steering gear needed attention

At the time of the tests both Gipsy models had clocked relatively high mileages-11,000 for the short wheelbase version and 7,000 for the long-wheelbase. This may have explained a considerable difference between them with regard to steering. The short wheelbase was "light" to the point of being almost dangerous before the "feel" had been mastered, whilst the long wheelbase was heavy.

When I first took over the short-wheelbase Gipsy I found the job of overtaking a stationary vehicle when another was coming towards me a very delicate matter. After some use and treating the steering with extreme care I found no difficulty except after having driven the long-wheelbase vehicle. The latter Gipsy had such heavy steering that it was very tiring to drive for any distance, and I can only assume that the steering systems of both test vehicles were in need of some maintenance work.

Apart from the steering I found the Gipsy quite a pleasant vehicle to drive, although there was a definite atmosphere of utility about the cab design. Some people would not like the lack of adjustment to the driver's seat, but the fact that it is fixed did not worry me. All controls are well placed and there is adequate storage space for small items in compartments in the doors and a small lockable cubby box.

The Gipsy is well provided with instruments, including engine temperature and oil pressure gauge, but ammeters fitted to the test vehicles are optional. There are warning lights for main beam, flashers and ignition; unfortunately it was difficult to see the flasher warning. An interior mirror is standard, but this is about the only flimsy item on the Gipsy and difficult to adjust to the best position— I proved both points when I was trying to do this and ended up with half the glass in my hand.

Recirculatory heaters in the vehicles are effective and adequate ventilation is provided for. Sun visors were also provided but as these were of tinted amber they were not much use when driving against a low sun.

As tested—that is with plastics hardtop—the Austin Gipsy has a basic price of £730 for the short-wheelbase version and £795 for the long-wheelbase. Specification of a diesel engine adds £105 and £110 respectively and examples from the optional extras fitted are: seating for six people in the rear of the long wheelbase model, £25 10s., ammeter £1 17s. 6d., heater and demister unit £10, and sun visors £1 10s. each.