OGE MOO

Page 92

Page 93

Page 94

Page 99

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

by Tony Wilding, MIMechE, MIRTE

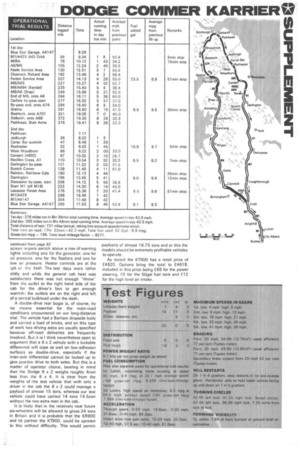

ONE of the first British makers to fit the Perkins 8.36-litre 179 bhp V8 in a goods vehicle was Dodge. This engine is now standard in a number of models made by this section of Chrysler United Kingdom Ltd, one of them being the KT900 6x4 rigid. On a recent road test and operational trial, an example of this chassis performed very well, returning a satisfactory fuel consumption at relatively high average speeds.

Fuel consumption over the 731-mile operational trial was 8.9 mpg for an excellent overall average speed of 42.2 mph. With the extension of M6 beyond Shap, about an hour has been taken off the journey time to Scotland for this class of vehicle and this was a factor in enabling us to record the shortest time yet achieved for the 376-mile first leg of our operational trial route. Only eight hours 36 minutes were •needed for this distance on the first day and eight hours 46 minutes was enough for the 355-mile return journey even though this included the very hilly A68.

Acceleration times were better than we have obtained on most tests of trucks running at a similar weight but brake stopping distances were a little poorer than the average. There was some lag, in brake operation which explains this: maximum deceleration, at 77 per cent, was well above average.

The Dodge can be praised for the standard of its under-cab insulation; the level of noise entering the cab was low and less than on other vehicles tested with the same Perkins power unit. The model has a first-class tilt cab with excellent all-round visibility—marred somewhat by flat-glass mirrors which do not give an adequate view to the rear and sides of a vehicle for my liking. • A suspension-type driver's seat was fitted in the K1900 I tested which insulated one from most of the road shocks reaching the cab through the rather harsh front suspension. There was some front-end bounce on rough surfaces and "nod" induced by the engine when pulling hard at about 2100 rpm. This made life less comfortable for the passengers than for the driver, especially the second, who gets rather cramped in the middle of the cab--on the driver's side of the double-passenger seat; though a third man would seldom be carried on distance work.

The Dodge 500 Series, of which the KT900 forms part, was the first to be introduced in this country offering operators a wide choice of mediumand heavy-weight models with a variety of options to meet their particular requirements. As well as the KT900 6x4 there are, at the top end of the range, the KR900 6x2 for the same weight of 22 tons, as well as 24/28-ton gross tractive units. All these have the Perkins V8.510 as standard and these chassis also share with the 6x4 a Chrysler five-speed direct-top synchromesh gearbox.

There is the option in most cases of a six-speed overdrive version and it is a pity that this optional box was not fitted in the test vehicle; it would most certainly have enabled an even better fuel consumption result to be obtained. For the type of running encountered on our operational trial--mainly trunk roads—it would always be worth the extra £44 that the overdrive box costs.

A Chrysler gearbox is the best heavyvehicle synchromesh box that I've yet encountered on a British truck. The change action is no heavier than a normal constant-mesh unit and the "gateis well defined so that gear selection and engagement is always relatively easy. The ratios are well chosen although they did not match all that well with the 5.57/7.60 ratios in the Eaton two-speed axles on the test vehicle.

In general the electrically operated axle change system worked well but there were times when it seemed that the change was not made in both axles simultaneously and there were missed engagements. This occurred more often when I was driving than when the Chrysler test driver was at the wheel and it was usually when changing to low axle ratio. By modifying the recommended technique and not depressing the clutch but "blipping" the accelerator after pre-selecting low ratio there was a more reliable change to "low".

The test vehicle had the optional power steering—essential in my view with a 6-ton front axle load--and while this kept driving effort down there were rather a lot of turns from lock to lock. As is common with ram-type assistance, there was some lag before the power started to help the driver and it needed sharp anticipation to ease off the steering to avoid over-correcting.

There was some lag felt also in brake application, which is illustrated by the big difference between the Tapley readings for peak efficiency of 77 per cent and the actual figures for overall retardation as represented by the stopping distances-40 per cent from 20 mph and 43 per cent from 30 mph. Nevertheless, braking figures are quite respectable and there could be no complaint. about the operation of the brakes on the road. The lag was not enough to cause difficulty and it was possible to control retardation to a fine degree.

Initial brake tests, acceleration checks and gradient-restart ability assessments were carried out at the Motor Industry Research Association test ground near Nuneaton during a break in the first day's journey on the operational trial. (The road surface was very wet at the time so brake tests were repeated later near Luton to obtain the figures quoted in the table.) Even with the direct-top gearbox, the Dodge six-wheeler tested was a fast vehicle, as is revealed by the high average speeds recorded on most of the motorway sections of the run. At the governed engine speed of 2,800 rpm the maximum road speed was about 54 mph but there was enough power to maintain an engine speed of 3000 rpm in top on the flat (57 or 58 mph) and some fuel was being delivered even at 3200 rpm which produced 61 mph.

We were at maximum speed for almost all the motorway running, so it is evident from the results that the Dodge KT900 scores well on fuel economy. This illustrates the value of having power in excess of the absolute minimum required.

On the more arduous part of the route—the undulating A68—fuel consumption did not worsen to any great extent. On the worst section it was 8.2 mpg and over the 31 miles between West Woodburn and Consett, the average speed was 26.7 mph.

On these operational trials, full regard is taken of legal speed limits. The power-to-weight ratio of 8.1 bhp per ton was therefore beneficial in allowing good average speeds on the run over the Tweedsmuir Hills 51 miles at 35.9 mph—and on the similarly twisting but hillier road from Pathhead to Rochester-66 miles at 33.0 mph; it was not the result of overfast running.

The relatively high power-to-weight ratio was also seen to advantage on the main hills on the route. As usual, figures were taken on the three which are met on the second day of the 731-mile test. Carter Bar on the border between Scotland and England measures 1.8 miles long and has a general gradient of 1 in 13/14. Speed of the vehicle at the start of the climb was 40 mph and third /high was just right for most of the ascent, with the speed varying between 16 and 20 mph. Near the top the slope increases to about 1 in 9 and here third /low was needed and speed dropped to 10 mph. After this, a change to high axle ratio was made and the speed reached 16 mph at the summit. Total time for the climb was 5min 55.5sec.

The much shorter 0.6-mile--and steeper—up to 1 in 5—hill at Riding Mill generally calls for a vehicle's lowest gear and so it was with the Dodge. We almost made the steepest part in second /low but a further change down was essential on the steepest part, and engagement of first was not completed satisfactorily. This is often the case on these tests and after the unplanned stop and restart the Dodge quickly reached maximum speed in first/low—about 6 mph—and this was held to surmount the most difficult part of the climb. Then changes up to second followed by third before reaching the top at a speed of 12 mph in third /high. The climb had taken a total of 3min 22.5sec.

Castleside hill is almost as steep as Riding Mill-1 in 5.2 at one point—but is longer. The 0.7-mile took 3min 37sec and while the Chrysler test driver was prepared for quick gear changes this time and cleared the 1 in 5.25 at 5 mph in second /low a later change on a section of similar severity produced a difficultya missed axle change—and there had to be a first,/low restart. At the top, third/ high was in use and speed was 18 mph.

The Dodge was a relatively easy vehicle to drive, easy to handle and with light controls so that the test was not particularly tiring. Mental effort was needed in concentrating on the steering but once accustomed to its character, which needed 100 miles of driving, little attention needed to be paid to this aspect of driving.

The driver of the KT900 and other models in the Dodge 500 Series has a pretty agreeable area in which to do his job. The seat is. comfortablia and the cab has a very good standard of interior trim. All hand controls and ,pedals are well placed and the all-round visibility is excellent. The top edge of the windscreen is fairly low and while this was no problem for me (a six-footer l arid could be an advantage in sunny conditions, a very tall. driver could perhaps find the panel above the screen somewhat obtrusive.

Whereas on most present-day vehicles with a combined parking and secondary control valve this unit is located Out of the way, and normally on the right-hand side of the seat, Dodge fit theirs close to the scuttle on the

Access to the cab of the Dodge from each side is easy but across-cab movement is hindered by the protrusion of the engine cover and the auxiliary-parking brake control valve.

left-hand side of the steering wheel and dash. This may be aesthetically bad especially with the number of pipes leading from the valve and it might slightly obstruct a driver moving across the cab to leave by the nearside door. But, on the credit side, the control is convenient to the driver, is easier to apply than one placed out of the way and the driver can see quite easily whether the parking brakes are applied.

The instrument panel is positioned directly in front of the driver and while one of the steering wheel spokes impedes clear view of the speedometer when the vehicle is running in a straight line, all the instruments can be read easily. These include an ammeter, fuel meter and a water-temperature gauge which are to the left of the speedometer. On the right is an engine rev counter and the air pressure gauges and the heater fan and wind screen wipers switch above a row of warning lights including one for the generator, one for oil pressure, one for the flashers and one for low air pressure. Heater controls are at the left of the dash. The test days were rather chilly and while the general cab heat was satisfactory there was not enough "throw" from the outlet to the right hand side of the cab for the driver's feet to get enough warmth; the outlets are on the right and left of a central bulkhead under the dash.

A double-drive rear bogie is, of course, by no means essential for the main-road conditions encountered on our long-distance trial. The vehicle had a Barham dropside body and carried a load of bricks, and on this type of work two driving axles are usually specified because off-road deliveries are frequently involved. But it is I think nevertheless open to argument that a 6 x 2 vehicle with a lockable differential will cope as well on low-adhesion surfaces as double-drive, especially if the inter-axle differential cannot be locked up to give positive drive to both axles. But this is a matter of operator choice, bearing in mind that the Dodge 6 x 2 weighs roughly 4cwt less than the 6 x 4. It is clear from the weights of -the test vehicle that with only a driver in the cab the 6 x 2 could manage a payload of almost 15 tons, whereas our test vehicle could have carried 14 tons 14.5cwt without the two extra men in the cab.

It is likely that in the relatively near future six-wheelers will be allowed to gross 24 tons in Britain and it is probable that the KR900 and its partner the KT900, could be uprated to this without difficulty. This would permit payloads of almost 16.75 tons and at this the models should be extremely profitable vehicles to operate.

As tested the KT900 has a retail price of £4520. Options bring the total to £4619, included in this price being £65 for the power steering, £9 for the 50gal fuel tank and £12 for the high level air intake.