A Flexible

Page 48

Page 49

Page 50

Page 53

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

but Sturdy 5-tonner

By Laurence J. Cotton, M.I.R.T.E.

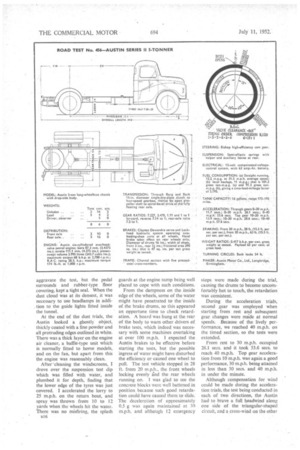

MY impression of the Austin Series II long-wheelbase 5-tonner after a 125mile test, which included a trial on the cross-country track and other sections of the Motor Industry Research Association's proving ground, was that there could be little wrc cg in its general design. However, after experience on the pavd and rough-country sections, I Would advocate the use of front-suspension shock absorbers on vehicles that are likely to operate under rough conditions overseas.

When the Series II model was introduced, the major difference from the preceding design was a new all-steel sound-insulated and dust-proof cab with space for a driver and two mates. I had ample opportunity of appraising this innovation during the trials when, in addition to myself, there were a co-driver and a photographer sitting abreast on. the bench-type seat, and two sizeable cases occupying a fair proportion of the floor space, at the near side.

In the Series II range, the rear of the cab has been moved back 4 ins. from the engine cover, and ,the interior width increased to 5 ft. 2 ins., thus adding to crew comfort—a feature which has been well studied in the whole design.

To keep the cab cool, the engine cover has a double skin with an asbestos lining, and Fibreglass insulation is used in the roof and down the back of the cab to waist level. The ventilation arrangements include fulldrop side windows, a large swivelling panel in each door window, and fresh-air ducts at floor level. '

Extra equipment available corn.prises one or two Smith's heaters mounted above the squab panel in

the engine compartment supplying warm air downwards into the interior and upwards to the de-misting apertures. Control flaps, in conjunction with water circulation taps, enable the heating units to be converted to forced-air ventilators fed with cool air from an intake behind the radiator grille.

Another development has been the "biscuit "-type six-point mounting of the cab, using widely-spaced circular rubbers on raised brackets at the . centre, and two similar supports mounted on cross-members in line with the front and back of the cab. In place of the centrehinged bonnet, the Series II has an alligator-pattern cover which is hinged at the rear. The appearance has been improved by blending the• radiator grille, wings and scuttle, and fitting the head lamps flush with the wings. Glass corner panels at the rear of the cab are standard.

There have been detail modifications to the chassis, and comparing the-former Austin 5-tonner, which I tested three years ago, with the pre ,ent model, the brake frictional area has been increased from 343 sq. ins. to 390 sq. ins. This alteration has been made by employing wider shoes at both axles, and from experience of fade-testing, I assessed the Austin as being probably the best in its class for consistent braking with hot drums. The braking is well matched to the performance of the lorry.

Sustained Performance The six-cylindered overhead-valve petrol engine used in the 5-tonner is not hard-pressed to develop 68 b.h.p. at 2,700 r.p.m. because the same power unit, with head change and minor alteration, as employed in the Austin fire-engine, has an output of 100 b.h.p. This indicates that in its conventional form, the engine performance should be well sustained without need for frequent attention. There is nothing unconventional in the four-speed straight-toothed gearbox or spiral-bevel final-drive unit, which are connected by a two-piece propeller shaft with Hardy-Spicer couplings and a centre bearing suspended from a cross-member.

Standard tyre equipment for the 5-tonner is 7.50-20-in., giving a permissible gross weight of 8 tons 5 cwt. This should be distributed in the proportion of one-third on the front axle and two-thirds on the twin equipment at the rear. With large concrete blocks equally spaced along the body, the ratio was almost correct on the test vehicle, 30 per cent, of the weight being carried at the front. There was slight overloading at the rear axle amounting to 6 cwt. which, in theory, meant each tyre was carrying 1+ cwt. more than its advocated capacity. This weight ratio is good for a semi-forward-control vehicle. Under normal conditions the photographer has independent transport during road tests, but as it was claimed the cab could accommodate three in reasonable comfort, I changed the procedure for the day. There was no discomfort in fitting in two passengers and the driver and leaving ample elbow room for gearchanging.

After a rough check on the speedometer for accuracy, I found the Austin could cruise comfortably at 40 m.p.h. and the maximum speed on level ground, where the road permitted such tests, was approximately 48 m.p.h. Although such speeds are not legal for a commercial vehicle operating in Britain, there are many overseas territories where the high cruising speed would be permitted, and from its behaviour the engine seemed to like it.

The Austin Motor Co., Ltd., made no objections to my plans for putting the 5-tonner through stringent tests, so the first objective at the M.I.R.A. track was the rough-country section which appears more pot-holed at every visit. There are various surface conditions, ranging from upstanding bricks and rubble to shingle and deep ruts. Undoubtedly tyres suffer as much risk of damage as the suspension, and as the tyres were inflated to maximum pressure for normal road work, most of the bumps were absorbed in the suspension.

After three miles of severe handling, the wheels being deliberately directed into the deeper potholes, the Austin remained intact apart from the radiator grille fairing, which had overridden the bumper bar on one side. This at least gave some indication of the cab Movement in relation to the chassis, because the bumper bar is attached to the frame. By

employing a floating mounting for the cab, there is practically no stress passed on to the structure when driving along an unmade road. The fairing, which is a purely decorative narrow strip of metal, filling the gap between grille and bumper bar, was easily returned to its rightful position.

Shock Absorbers Needed I have seen suspension fractures, axles move out of position, steering gear break, petrol tanks split and radiators tear open in the first trip of vehicles along the Belgian pave, but no such fate beset the Austin, which put up a good performance without any vital part becoming dislodged or broken. Particularly on this section, I would have appreciated some control over the suspension. The addition of shock absorbers at the front axle might have stopped me from being bounced from my seat, as happened on one occasion.

The Austin also survived the " washboard " section without coming to harm, It kept a reasonably straight course at 20 m.p.h. along the oblique corrugations and although the wheels frequently bounced off the ground, which happens with goods vehicles and passenger cars alike, there was no unusual disturbance at the steering wheel.

The Austin lorry has better dustproofing to the cab than many British cars. This I discovered after half an hour's work in the dust tunnel when, although there was a heavy build-up on the screens and around the doors, no dust penetrated through to the cab. I had expected to find some seepage through the floorboards, purposely making gear changes and operating the brakes in the tunnel to aggravate the test, but the pedal surrounds and rubber-type floor covering, kept a tight seal. When the dust cloud was at its densest, it was necessary to use headlamps in addition to the guide lights fitted inside the tunnel.

At the end of the dust trials, the Austin looked a ghostly object, thickly coated with a fine powder and all protruding edges outlined in white. There was a thick layer on the engine air cleaner, a baffle-type unit which is normally fitted to home models, and on the fan, but apart from this the engine was reasonably clean.

After cleaning the windscreens, I drove over the suspension test dip which was filled with water, and plumbed it for depth, finding that the lower edge of the tyres was just covered. I accelerated the lorry to 25 m.p.h. on the return bout, and spray was thrown from 10 to 12 yards when the wheels hit the water. There was no misfiring, the splash guards at the engine sump being well placed to cope with such conditions.

From the dampness on the inside edge of the wheels, some of the water might have penetrated to the inside of the brake drums, so this appeared an opportune time to check .retardation. A board was hung at the rear of the body to warn other drivers of brake tests, which indeed was necessary with some machines overtaking at over 100 m.p.h. I expected the Austin brakes to be effective before starting the tests, but the possible ingress of water might have disturbed the efficiency or caused one wheel to pull. The test vehicle stopped in 28 ft. from 20 m.p.h., the front wheels locking evenly and the rear wheels running on. 1 was glad to see the concrete blocks werc well battened in position. because such good retardation could have caused them to slide. The deceleration of approximately 0.5 g was again maintained at 30 m.p.h. and although 12 emergency

stops were made during the trial, causing the drums to become uncomfortably hot to touch, the retardation was consistent.

During the acceleration trials, second gear was employed when starting from rest and subsequent gear changes were made at normal speeds. Because of the lively performance, we reached 40 m.p.h. on the timed section, so the tests were extended.

From rest to 30 tn.p.h. occupied 26.1 secs. and it took 53.6 secs, to reach 40 m.p.h. Top gear acceleration from 10 m.p.h. was again a good performance, 30 m.p.h. being attained in less than 30 secs. and 40 m.p.h. in under the minute.

Although compensation for wind could be made during the acceleration trials, the test being conducted-in each of two directions, the Austin had to brave a full headwind along one side of the triangular-shaped circuit, and a cross-wind on the other

two sides during the consumption trials: the effects of this were felt on the degree of accelerator movement. During straight running, three laps of the course were covered at 31.5 m.p.h. ' average speed, fuel being used at the rate of 12.2, m.p.g. According to the time-load-mileage factor, the Austin is shown to be among the most economical of its class.

With one stop to every mile, representative of local haulage, •the fuel return was 11 m.p.g. which again indicates the Series II is not a thirsty

vehicle. Taken over the day's work, which had called for a fair proportion of intermediate gear work, the Austin did well to return to Longbridgewith 5-6 gallons of petrol remaining in the tank after 125 miles running.

Before leaving the proving ground, use was made of the steering pad to measure the turning circles. On the vehicle supplied, both locks measured 57 ft. 6 ins., indicating that the steering stops required a small adjustment to give the 54 ft. turning circle which is specified for the long-wheelbase model.

In summarizing the day's trials, I was particularly pleased with the vehicle which, as a model straight from the production line, was obviously not .tuned up to give unusual performance, in fact the ignition timing wa& reset in the first 10

miles of • my test. The cab in its standard form would pass any overseas dust test and the heating and ventilation arrangements afford• comfort in extremes of climates.