u r ° mat T 0 find a solution of any national problem

Page 43

Page 42

Page 44

Page 47

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

nowadays, it seems to be necessary to turn to a formula expressed in the Words: "In America they do such and such," or: "On the Continent they do it this way." These phrases

far too often trip lightly off the tongues of selfprofessed experts.

Take the case of the " expert " who has undertaken a fortnight's tour of Europe. "In Sprognovia," he says, "they operate single-deck battery-electric buses with room for 150 passengers and no driver or conductor. If we had vehicles like that, instead of these out-of-date 56-seat double deckers powered by fuel we have to import from countries that don't want to let us have it "—and so on. Incidentally, battery-electric single-deckers are by no means unheard of on the Continent, and, in fact, were suggested for use on a link route in Birming ham quite recently. .

But the idea put forward by our expert is different.

What he omits to say is that in Sprognovia vehicles run at 45-minute intervals. The minimum fare, or maybe the standard fare, is 2s., and the operating company makes its profits on such side-lines as supplying all the electric current in the locality.

Then, again, we might be led to believe from references to American transport technique that problems of falling revenues and rising costs .do not exist in the U.S.A. Nothing could be farther from the truth. Both in the United States and on the Continent, the problem of solvency occupies the attention of every operator, but the method adopted in these countries are far from being the answer to our problems.

Operational conditions vary enormously from country to country and from route to route. The standard of service is rarely as high as in this country. Even in Paris, which has long been considered a model in the provision of public transport facilities, the standard fare is now 15 francs, which is equivalent to 4d., and even on the boulevard routes only a 10-minute frequency is usual.

A fresh breeze was let into the hot air of current discussions by Mr. W. H. Hall, general manager of LiPirprpool Transport Department, in his paper last year TS on public transport in America. He pointed out that the minimum fare on American city buses was in many cases ls. 4d., despite which the undertakings were faced with deficits the size of which would make our city fathers wish they had never entered the field of public transport. Coupled with this, although Mr. Hall did not say so, it does not appear that the same frequency of service

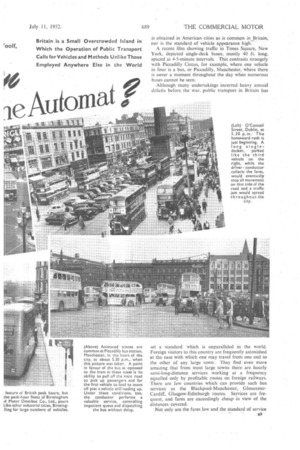

(Above) Animated scenes are common at Piccadilly bus station, Manchester, in the heart of the e;ty, at about 5.30 p.m., when this picture was taken. A point in favour of the bus as opposed to the tram in these cases is its ability to pull off the main road to pick up passengers and for the first vehicle to load to move off past a vehicle still loading up. Under these conditions, too, the conductor performs a valuable service, controlling impatient queus and dispatching the bus without delay.

is obtained in American cities as is common in Britain, nor is the standard of vehicle appearance high.

A recent film showing traffic in Times Square, New York, depicted single-deck buses, mostly 40 ft. long, spaced at 4-5-minute intervals. This contrasts strangely with Piccadilly Circus, for example, where one vehicle in four is a bus. or Piccadilly, Manchester, where there is never a moment throughout the day when numerous buses cannot be seen.

Although many undertakings incurred heavy annual deficits before the war. public transport in Britain has

set a standard which is unparalleled in the world. Foreign visitors to this country are frequently astonished at the ease with which one may travel from one end to the other of any large town. They find even more amazing that from most large towns there are hourly semi-long-distance services working at a frequency equalled only by profitable routes on foreign railways. There are few countries which can provide such bus services as the Blackpool-Manchester, GloucesterCardiff, Glasgow-Edinburgh routes. Services are frequent, and fares are exceedingly cheap in view of the distances covered.

Not only are the fares low and the standard of service high, but the degree of comfort and convenience offered by British Services are incredible to anyone not familiar with this country. Except at peak hours, seats are provided for every passenger who wishes to travel, and the buses are invariably clean, smooth-running and efficient Their time-keeping is impeccable. In America, competition from 48m. private cars makes the public transport operator's life a misery. In this country, the Englishman's bus is his Rolls-Royce.

Are we then to jump at the suggestion that this country needs 40-ft-long single-deckers, seating 12 passengers and accommodating a further 70 with Varying degrees of discomfort and operated by a harassed driverconductor ? What effect would these vehicles have on our already congested roads on .which saturation is daily coming closer ? Is our friend the conductor to disappear, to be replaced by a bad-tempered automat whose two feet alternatively play the accelerator pedal and brake, leaving the transmission in the Control of a Birmingham boffin? His hands would be occupied with a poweroperated steering wheel, a ticket-issuing machine, a change-giving machine and two, or even three, sets of door-operating controls. . How under these conditions can any man, however well-paid, be expected to assist passengers to board, help them find their destinations, inform them about other services they. may .need, and maintain control of both the vehicle and its load ?

Discrepancy in Weight

Single-deckers to-day arc beginning to weigh 9 tons unladen and to consume fuel at the rate of 8-10 m.p.g. Our old-fashioned double-deckers, however, are still only hovering near the 8-ton mark and continue to return 11-14 m.p.g. Already, the occasional over-worked conductor discourages short-distance passengers and misses fares. While vehicles become daily more expensive, complex and specialized, traffic continues to fall and over-crowding at peak hours does not diminish.

Another popular line of argument is that we need trams. Apart from those sincere engineers who support the idea that the modern tram can answer our transport problems, this view is expressed too often by sentimental old gentlemen who refuse to. see that trams cannot fit into the modem pattern of transport. operation. Trams are undoubtedly wonderful "queue-shifters," but it should be remembered that they have to be operated in competition—and not side-by-side—with buses which can be diverted from town operation on off-peak days so that their revenue-earning capacity is kept constant.

There are two days a week when traffic is frequently bound out of town. A transport system tied to the main streets of a city is useless on Saturday and Sunday as the vehicles cannot be used to take passengers to outlying parts.

Too Big and Heavy

Let us not have any more comparisons between trams and buses. The old E.1 tram which served London from 1907 until the conversion to bus working, seated 78 passengers and could accommodate probably 20 more standing. It was 34 ft. Sins. long, 16 ft. high and 7 ft. wide. It weighed 12 tons.

These figures indicate the basic disadvantage of the tram—its bulk and weight The second figure, it must be recalled, is a function of the vehicle weight and of the weight of track, cables and sub-stations which were part of the tram system. These items required far too much outdoor labour. Nowadays almost every part of the bus and its ancillary equipment can, be serviced, maintained and repaired at a central depot.

What, then, are the basic requirements of modern passenger transport? First, a vehicle that is cheap to a10 buy, maintain and operate, and which will be sufficiently adaptable to enable its qualities to be deployed to the maximum. It must not be incapable of meeting constantly changing demands.

Secondly, a means must be found not only for meeting the occasional maximum demand at the lowest possible cost, but also the undetermined and incalculable need which exists between the extremes. It is poor design to consider only the extreme condition. In between peak hours there are still passengers who wish to travel, preferably in comfort.

Part of the difficulty of bus (and tram) operation to-day is the competition offered by the private car. Bad services—infrequent and inconvenient—encourage the private motorist. ..Good services, at low cost, should encourage motorists, cyclists and pedestrians to use public transport. Staggering of office, school and factory hours would do much to help, and this would produce.

a net reduction in operating costs. .

This brings us to the third requirement of modern

passenger road services. They must attract custom. It used to be said that if a service, was put on, people would make use of it. That is no longer completely true. Comfortable buses, meeting the needs of .the public as closely as possible, promote traffic. If they are well-lit, well-ventilated, clean and bright, they repay the passenger, in some degree, for his misfortune in being able to travel only at peak hours.

Even greater recompense is offered by a cheerful conductor. He does much to waken a rush-hour bus load from apathy that follows a hard day's work. Several conductors of an optimistic frame of mind soon acquire much good will for an undertaking, as well as encourag, ing people to travel on their particular routes. In fact, the value in terms of £ s. d. of the efficient, friendly bus crew can almost be estimated,' for most operators can produce letters of appreciation from 'old ladies, disabled people and parents of small children offering thanks for the kindness and courtesy shown to them. In the absence of conductors, such passengers may find other means for travelling.

Obviously, only a compromise solution can be found for all these requirements. If a conductor is to be

carried, and in my view he is indispensable in busy British cities, his work must be eased or mechanized, Passengers must be able to move into, out of and through a vehicle as quickly as possible so that low steps, wide doors, ample gangways and windows which enable every passenger to see where he is, however full the interior, are essential. Furthermore. it is cheaper and better to ease the conductor's lot than to provide the driver with a trick transmission which is supposed to compensate him for doing two men's work.

As so often is remarked, the variables in the com promise are comfort, cost and convenience. More comfort and convenience for passengers mean higher cost. When these are related to workshop technique the same applies; convenient vehicles from the maintenance mechanic's point of view are often costly ones. Comfortable Vehicles from the general manager's viewpoint are those which never require cleaning, painting, overhauling or replacement—one might say trams.

If we take the view that the questions of traffic control and service organization have been answered and that there are no problems still outstanding, there remains the question of what vehicles are to be used. The obvious answer is the vehicle which carries the maximum number of passengers compatible with the three " C's" and With the general road conditions pertaining now and likely to exist in 10-15 years time.

There have been several developments recently which point the way, One is the Bristol Lodekka bus which improves on the standard features of the double-decker by decreasing the overall height so that it can be operated even where there are low bridges. It also provides a low step at the entrance which must undoubtedly improve loading times and be a great help to handicapped passengers.

Compromise Solutions

Then there is the type of single-decker operated by Southampton Corporation, designed expressly for both one-man and two-man operation. This is a compromise which promises well for the conditions in Southampton and could probably fit in the pattern of other towns.

On the other hand, it is not as universal a compromise as the double-decker was in the early days of passenger transport. Having regard to the layout of most British towns and cities and to the extraordinary concentration of traffic on our roads, it would seem that something new in the way of a double-decker is sadly needed. Extra passenger space achieved at the cost of road space is a short-term policy. How, for example, could London Transport hope to run 150200 vehicles an hour though Oxford Street or the busier parts of the East End if each bus was 35 ft. long? Again, it is frequency of vehicles rather than the number of passengers which each vehicle can carry which counts in these circumstances.

What is required is a doubledecker having features similar to those . of the underfloor-engined single-decker. The underfloor engine position for double-deckers is not practical because the floor height would be raised too much, but, considering the improve ments in structural design which have taken place. recently, why should we not revert to the side-engine layout?

With the engine moved farther to the rear and mounted in a chassisless or integral body—which could easily be made stiff enough Co absorb engine vibrations —this would prove ideal for to-day's conditions. The engine might even be situated at the rear, as in the Saurer bus, with the staircase over it. The whole floor would be devoted to passenger space. The advantages of light weight, single tyres all round, even weight distribution, and a wide, low front entrance would be particularly valuable.

Room for Development

Moreover, such a vehicle could be put to fuller use. Both a front and rear entrance could be provided. Passengers would use the front. one in off-peak hours, leaving at the rear, or, if their journeys were more than one or two stages, they could move back to the rear staircase and ascend to the upper deck. This would be fitted with 32-36 seats, depending on whether the 30-ft. length for double-deckers became permissible. The lower deck would have 12-20 seats. The conductor could be seated at the rear on the off side facing.the pavement. In peak hours the entry and exit arrangements could probably be conveniently reversed.

There would be room for up to 24 standing passengers, either in the lower-dect gangway or on the rear platform. A maximum capacity of 80 passengers should be feasible, and the conductor's work would be eased because he could devote his attention to the shortdistance passengers on the lower deck, leaving upper deck passengers in peace until they descended, or until he had time to deal with them. Doors front and rear, under the control of the driver and conductor respectively, would be essential. By leaving the front door in the control of the driver, the conductor's work would be further eased.

A vehicle of this size would probably weigh up to 7 tons unladen. Its extra capacity and value as a queueshifter would soon prove valuable, whilst its layout would not prevent it from being used on Saturday and Sunday to take passengers to the beach or to the local races for service as a mobile grandstand.