School for safety

Page 65

Page 68

Page 69

Page 71

Page 72

Page 73

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

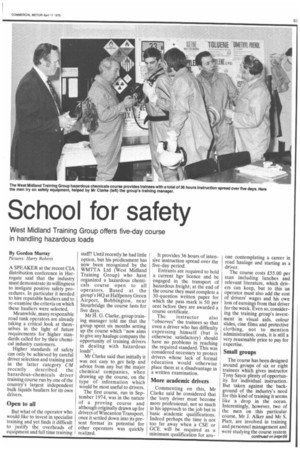

West Midland Training Group offers five-day course in handling hazardous loads

By Gordon Murray Pictures: Harry Roberts A SPEAKER at the recent CIA distribution conference in Harrogate said that the industry must demonstrate its willingness to instigate positive safety procedures. In particular it needed to hire reputable hauliers and to re-examine the criteria on which these hauliers were selected.

Meanwhile, many responsible road tank operators are already taking a critical look at themselves in the light of future requirements for higher standards called for by their chemical industry customers.

Higher standards of safety can only be achieved by careful driver selection and training and in the latter category CM recently described the hazardous-chemicals driver training course run by one of the country's largest independent bulk liquids hauliers for its own drivers.

Open to all

But what of the operator who would like to invest in specialist training and yet finds it difficult to justify the overheads of equipment and full time training staff? Until recently he had little option, but his predicament has now been recognized by the WMTTA Ltd (West Midland Training Group) who have organized a hazardous chemicals course open to all operators. Based at the group's HQ at Halfpenny Green Airport, Bobbington, near Stourbridge the course lasts for five days. Mr H. G. Clarke, group training manager told me that the group spent six months setting up the course which "now aims to give any haulage company the opportunity of training drivers in dealing with hazardous loads".

Mr Clarke said that initially it was not easy to get help and advice from any but the major chemical companies, when drawing up the course, on the type of information which would be most useful to drivers.

The first course, run in September 1974, was in the nature of a proving course and although originally drawn up for drivers of Wincanton Transport, once it settled down into its present format its potential for other operators was quickly realized. It provides 36 hours of intensive instruction spread over the five-day period.

Entrants are required to hold a current hgv licence and be engaged in the transport of hazardous freight; at the end of the course they must complete a 30-question written paper for which the pass mark is 50 per cent before they are awarded a course certificate.

The instructor also "observes" the trainees so that even a driver who has difficulty expressing himself (but is otherwise satisfactory) should have no problems in reaching the required standard. This was considered necessary to protect drivers whose lack of formal education would otherwise place them at a disadvantage in a written examination.

More academic drivers

Commenting on this, Mr Clarke said he considered that the lorry driver must become more professional, not so much in his approach to the job but in basic academic qualifications. Indeed perhaps the time is not too far away when a CSE or GCE will be required as a minimum qualification for any one contemplating a career in road haulage and starting as a driver.

The course costs £55.00 per man including lunches and relevant literature, which drivers can keep, but to this an operator must also add the cost of drivers' wages and his own loss of earnings from that driver for the week. Even so, considering the training group's investment in visual aids, colour slides, cine films and protective clothing, not to mention administration, costs, it is still a very reasonable price to pay for expertise.

Small groups

The course has been designed around groups of six or eight trainees which gives instructor Tony Sayce plenty of opportunity for individual instruction. But taken against the background of the industry's need for this kind of training it seems like a drop in the ocean. Interestingly, however, two of the men on this particular course, Mr J. Alker and Mr S. Platt, are involved in training and personnel management and were studying the course system with a view to starting a similar one within their respective companies.

Of the total of 36 hours instruction at Bobbington 191/2 hours are devoted to theoretical work, and 91/2 hours to practical work, including fire fighting.

The remaining seven hours is taken up by the opening and closing address, general discussion, written papers and revision work—all of which adds up to a pretty busy five days. Most of the first morning was taken up by a review of the industry's safety record and a discussion covering the Petroleum (Inflammable Liquids) Order 1971, the Inflammable Substances (Conveyed by Road) (Labelling) Regulations 1971, the Organic Peroxides (Conveyance by Road) Regulations 1973 and the Petroleum (Organic Peroxides) Order 1973, all of which is pretty heavy stuff but it helps into perspective the care which authorities take in drafting rules for the movement of dangerous commodities.

Identifying samples

This was followed by product recognition and handling introduction, which involved the use of small chemical samples which had to be identified and classified as toxic, acid, inflammable etc, by smell and appearance, (i.e. colour, viscosity etc). Anyone contemplating this type of exercise would be well advised to sniff the stopper and not the container in order to preserve their sense of smell intact.

Immediately after lunch, Tony Sayce embarked on the hazardous and largely uncharted seas of product labelling, covering the Hazchem and Kemler systems. Considering that Tremcards will become a legal requirement in the UK later this year, there is still a great deal of confusion surrounding them and it is by no means certain that they will be entirely accepted in place of 'local' systems used in some countries.

Then followed an hour of basic mechanical principles covering the working of pumps and compressors and the theory of hydraulics, using cutaway models and other visual aids. The training group also has the inevitable black museum of damaged valves, discs, gaskets, etc, which add impact to this largely theoretical session. Day one was rounded off by another talk on product identification and handling and a film which took us through to 5.30 p.m.

Protective clothing

Day two got away to a fine start with a revision question paper which covered the previous day's work. The remainder of the morning was taken up with a description of some of the many types of protective clothing now on the market, their application to this particular branch of the industry and, most important, their correct use. Then came another two hours instruction in product handling (using visual aids) driver responsibility, including pre and post delivery safety checks, and details of compliance with various company safety procedures.

The afternbon session began with more product handling techniques and then went on to cover the basic mechanical prin ciples of non-return valves, couplings and hoses, using actual examples in the classroom.

The remaining periods of day two covered personal safety and safety equipment, using gas masks, eye washes and respirators and yet more instruction in product handling and the recognition of corrosive substances.

Day three featured a discus sion on accident and breakdown procedures, using the ICI tanker manual as a basis. This was followed immediately by the theory of fire fighting and the use of breathing equipment.

Fighting fires

After lunch the trainees had the chance to put their fire fighting theory into practice at a two-hour session. Under expert tuition from the airport fire officer, the men don protective clothing and actually tackle fires to see for themselves how effective or otherwise various types of extinguisher are against such things as tyre fires.

Then back to the classroom for another hour of instruction in documentation and the use of company forms, to round off the day.

Day four was nicely balanced between theory and practice; it included the theory of loading and discharge and the stability of loads and, after lunch, practical instruction in the use of ancillary equipment, correct use of hoses etc, using the training group's own Foden tanker. This old vehicle, now long out of service, has developed a number of defects with the passage of time, and is an ideal instruction unit. Indeed anyone running a training course might be advised to keep an old vehicle as a training aid; its usefulness can far outweigh its scrap value.

The final day of the course included a film Driver in Control, then the trainees went out again to the tanker. Each man was given a different Tremcard and he then had to make a fault finding tour of the old Foden, making allowance for the type of load he would be carrying.

The vehicle normally has about 20 faults which range from missing dipsticks, bald tyres, defective foot valves to incorrect markings.

Accident procedure

In the afternoon the same vehicle was used to simulate an accident, using a couple of cars.

The individual drivers then had to decide on a course of action depending on the type of chemical supposedly being carried and varying degrees of damage to the tank and the other vehicles involved.

Five days earlier when opening the course Mr Clarke told the trainees "the obvious is never obvious until it is pointed out, and that's what this course is all about". From their comments during the final day it was clear that the majority now agreed with him. THE AMSTERDAM SHOW in 1974 saw the appearance of the first fruits of the SeddonAtkinson combine in the form of a 38-tonne (37.4-ton) tractive unit. This was openly declared to be a prototype only, with the intent of sounding out market reaction, and with commendable enterprise SeddonAtkinson handed out trilingual questionnaires for comments from operators, engineers and the general public on the merits and demerits of the new truck. All the questions and answers are now hopefully resolved, as last Wednesday saw the official announcement of the new 400 range of trucks from SeddonAtkinson.

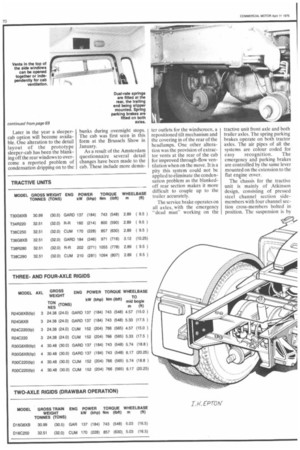

Tractive unit

The category which is likely to arouse the most interest contains the tractive units and these will be the first trucks of the new range to come on the market. The gcw range covered is quite extensive—from just over 30 tons with a Gardner 6LXB to a massive 60 tons with a 14-litre Cummins.

Singling out the 32-tonners from the category, the usual engine options are available from Cummins, Gardner and Rolls-Royce (in alphabetical order). The Cummins is the 250 rated at 170kW (228bhp) net installed, and a road test of the new Seddon-Atkinson fitted with this particular power unit is featured elsewhere in this issue. The Rolls-Royce Eagle produces 160kW (214bhp) at 2100rpm and the Gardner option is, of course, the in-line eight-cylinder 8LXB which produces 184kW (246bhp) at an unhurried 1850rpm.

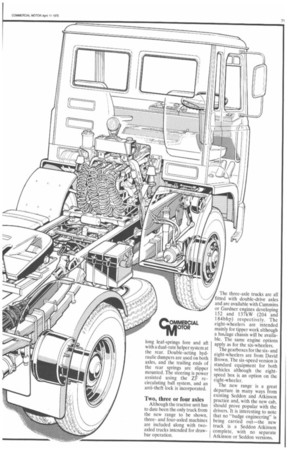

Some gearbox options will be available, but the "standard equipment" is the Fuller Roadranger RTO-9509A ninespeed range-change box in conjunction with a SeddonAtkinson spiral bevel hubreduction axle and a 355mm (14in) diameter twin-dry-plate Lipe-Rollway clutch. To generations of experienced Atkinson and Seddon operators and drivers the cab is the most obvious departure from tradition, being a completely new design which brings the combine right back into line with the continental opposition. The cab tilts to 60 degrees for major servicing although a hinged front panel provides access to the dipstick, radiator, heater and the switches for the air-pressure system.

Sturdy cab

The cab is of pressed steel construction and one neat design feature concerns the windscreen pillars which are 140mm (5.5in) wide at their base but are angled to appear slim to the driver's eye. At the top of the side windows there are opening sections fitted, similar to the Saviem, which can be opened independently or together for ventilation. On the prototype which appeared at Amsterdam the sun visors were neatly recessed above the screen and held by magnetic catches. They had a parallelogram action when pulled down across the screen, but on the production model this has been replaced by a standard flap-type visor. I think this is a pity as I thought the original layout was excellent.

The cab structure itself is a Seddon-Atkinson design manufactured by Motor Panels Ltd of Coventry. The doubleskinned sides of the engine compartment form girders which are 600mm (23.6in) deep at the front where they meet the box members of the cab frame. The frame below the front screen forms a full-width beam with a total depth of 350mm (13.8in). The top rail around the roof section is 175mm (6.9in) deep as is the dimension for the beam under the rear bulkhead, and, the double-skinned side walls are over 110mm (4.3in) think.

The interior of the cab was designed by Ogle, who suggested the light tan colour for the interior trim. Suspension seats are standard and these are trimmed with brushed nylon cloth, which is claimed to be more dirt resistant. Later in the year a sleepercab option will become available. One alteration to the detail layout of the prototype sleeper-cab has been the blanking off the rear windows to overcome a reported problem of condensation dripping on to the bunks during overnight stops. The cab was first seen in this form at the Brussels Show in January.

As a result of the Amsterdam questionnaire several detail changes have been made to the cab. These include more demis ter outlets for the windscreen, a repositioned tilt mechanism and the covering in of the rear of the headlamps. One other alteration was the provision of extractor vents at the rear of the cab for improved through-flow ventilation when on the move. It is a pity this system could not be applied to eliminate the condensation problem as the blankedoff rear section makes it more difficult to couple up to the trailer accurately.

The service brake operates on all axles, with the emergency "dead man" working on the tractive unit front axle and both trailer axles. The spring parking brakes operate on both tractor axles. The air pipes of all the systems are colour coded for easy recognition. The emergency and parking brakes are controlled by the same lever mounted on the extension to the flat engine cover.

The chassis for the tractive unit is mainly of Atkinson design, consisting of pressed steel channel section sidemembers with four channel section cross-members bolted in position. The suspension is by long leaf-springs fore and aft with a dual-rate helper system at the rear. Double-acting hydraulic dampers are used on both axles, and the trailing ends of the rear springs are slipper mounted. The steering is power assisted using the ZF recirculating ball system, and an anti-theft lock is incorporated.

Two, three or four axles

Although the tractive unit has to date been the only truck from the new range to be shown, threeand four-axled machines are included along with twoaxled trucks intended for drawbar operation. The three-axle trucks are all fitted with double-drive axles and are available with Cummins or Gardner engines developing 152 and 137kW (204 and 184bhp) respectively. The eight-wheelers are intended mainly for tipper work although a haulage chassis will be available. The same engine options apply as for the six-wheelers.

The gearboxes for the sixand eight-wheelers are from David Brown. The six-speed version is standard equipment for both vehicles although the eightspeed box is an option on the eight-wheeler.

The new range is a great departure in many ways from existing Seddon and Atkinson practice and, with the new cab, should prove popular with the drivers. It is interesting to note that no "badge engineering" is being carried out—the new truck is a Seddon Atkinson complete, with no separate Atkinson or Seddon versions.