What Motorways May Mean

Page 38

Page 39

Page 40

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

Radical Changes in the Country's Pattern of Internal Transport Should Follow the Construction of a Network of Roads Especially Designed

for High-speed Traffic

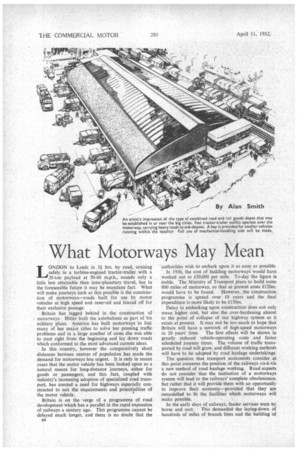

LONDON to Leeds in 3i hrs. by road, cruising safely in a turbine-engined tractor-trailer with a 20-ton payload at 50-60 m.p.h., sounds only a little less attainable than inter-planetary travel, but in the foreseeable future it may be mundane fact. What will make journeys such as this possible is the construction of motorways—roads built for use by motor vehicles at high speed and reserved and fenced off for their exclusive passage.

Britain has lagged behind in the construction of motorways. Hitler built the autobahnen as part of his military plans. America has built motorways to link many of her major cities to solve her pressing traffic problems and in a large number of cases she was able to start right from the beginning and lay down roads which conformed to the most advanced current ideas.

In this country, however the comparatively short distances between centres of population has made the demand for motorways less urgent. It is only in recent years that the motor vehicle has been looked upon as a natural means for long-distance journeys, either for goods or passengers, and this fact, coupled with industry's increasing adoption of specialized road transport, has created a need for highways especially con structed to suit the requirements and potentialities of % the motor vehicle.

Britain is on the verge of a programme of road development which has a parallel in the rapid expansion of railways a century ago. This programme cannot be delayed much longer, and there is no doubt that the n4

authorities wish to embark upon it as soon as possible.

In 1936, the cost of building motorways would have worked out to £50,000 per mile. To-day the figure is treble. The Ministry of Transport plans to build some 800 miles of motorway, so that at present costs £120m. would have to be found. However, the construction. programme is spread over 10 years and the final expenditure is more likely to be £150m.

Delay in embarking upon construction does not only mean higher cost, but also the over-burdening almost to the point of collapse of our highway system as it exists at present. It may not be too much to hope that Britain will have a network of high-speed motorways in 20 years' time. The first effects will be shown in greatly reduced vehicle-operating costs and faster scheduled journey times. The volume of traffic transported by road will grow, and different working methods will have to be adopted by road haulage undertakings.

The question that transport _economists consider at this point concerns the position of the railways vis-à-vis a new method of road haulage working. Road experts do not consider that the institution of a motorways system will lead to the railways' complete obsolescence, but rather that it will provide them with an opportunity to improve their economy—provided that they are remodelled to fit the facilities which motorways will make possible.

In the early days of railways, feeder services were by horse and cart. This demanded the laying-down of hundreds of miles of branch lines and the building of

several stations on the main routes at which the through trains had to stop. With the development of mechanized road transport, the effective radius that a railway depot could cover with its vehicles was increased. By the use of motorways, railway road feeder services could be expanded over even greater areas.

Motorways would make it possible for even more unrenntnerative short-distance, and even mediumdistance, railway lines to be closed, and for fewer railway depots to be kept up. The function of rail transport would be fast long-distance conveyance over the country's arterial traffic routes.

Journey-time Reductions

The most outstanding benefit of motorways will be in reducing the times taken to run certain journeys. To revert to the example quoted at the beginning of the article, the distance betwen London and Leeds is 190 miles. Limitations imposed by the present highway system and the regulations concerning drivers' hours mean that the average speed of a heavy vehicle running between the two cities comes down to 16 m.p.h., involving a total journey time of 12 hrs. If we assumed that on a motorway its cruising speed would be 28 m.p.h., the running time would be nearly 7 hrs., to which must be added a period for driver's rest, which makes the journey time 7khrs.—a reduction of over a third.

Savings in operating costs would also be substantial. The Institution of Highway Engineers has estimated that • by operating vehicles over a proper road system, fuel costs would be cut by 40 per cent. (a conservative estimate), tyre wear by 15 per cent, and repair expenses by 10 per cent. It is further calculated that on the

Birmingham-Bristol section of the proposed motorway, traffic using this route will save over Lim. a year.

These speculations, however, have been based on costings for present-day types of vehicle. There is no doubt that the motor industry will be quick to produce vehicles that will be able to take full advantage of motorways. What these models will be like depends on the new transport methods that will be adopted and the system that carriers create for handling various types of traffic.

In the transfer of much medium-distance distribution from rail to road, large depots might be established in or near the principal cities and these would be fed by the trunk-route railway trains. From them, maximumcapacity road vehicles would carry away loads on the motorways to smaller distributive depots. These establishments would serve as points of transfer in handling medium-distance road traffic, besides their .functions ancillary to the railways.

Tractor-trailer operation may be favoured for haulage work over the motorways. Motive units to haul 20-ton -.payloads at 50-60 m.p.h. (10 tons on the prime mover . and 10 ton on a trailer) would be expensive machines, and 'economy would demand their fullest employment. Their design should not present great difficulties to the

• motor industry. With engines of 200 b.h.p. or even more and rear axles of high ratio, they should return a fuel-consumption rate of 6 m.p.g. and their life should be much longer than those of vehicles operating over normal highways. Loads would be carried in containers of various sizes, 10-ton, 5-ton, 2-ton and 1-ton, made to fit platform dimensions, and depot handling of containers could be done by overhead gantries and fork-lift trucks.

Economy would also dictate that the prime movers be restricted to the motorway alone. If trailers had to be drawn on the ordinary roads, they could be detached for traction by normal-type machines. In fact, loads might be broken up at the sub-distributive depots, so that occasions when high-capacity units would need to be taken off the motorway Would rarely arise. The subdepots would be built just off the motorways, to which they would be linked by service roads.

Much of road transport's present value lies in its

ability to effect direct delivery without intermediate handling of the load. This advantage would be retained in many cases where single loads were large enough to justify direct haulage, as would be the experience of many ancillary users, but for general transport some copying of railway practice would be desirable to obtain fast, economical transport of mixed small consignments over motorway routes. Large single loads to be carried over motorway and ordinary road could best be taken by normal vehicles fitted with overdrives.

It is to be expected that advances in mechanical methods will be made, so that the load-transfer and sorting problem involved in general traffic may be largely overcome. Fuller advantage of mechanical-handling methods could be taken in the new road transport depots, which would be designed for their application, than in railway yards never laid out for their employment.

In passenger transport, the developments would be just as marked as in haulage. The most modern longdistance coaches already offer comfort at least comparable with rail travel: motorways will put road passenger transport in a more competitive position as regards speed. These conditions, and the comparative cheapness of road travel, will guarantee a greatly increased demand for express-carriage services of high frequency between various centres of population.

It may not be as necessary to build special vehicles for passenger transport on the motorways as might be the case in goods haulage. Many towns will be by-passed by the motorways and the need for coaches to run to and from urban terminals will demand the use of vehicles suited to normal roads. Coaches built for use on the motorways would have powerful engines and high-ratio transmission systems to enable them to cruise at about 70 m.p.h. Whilst faster speeds of the 100-m.p.h. order may be theoretically attainable, they may not be acceptable to passengers. Experience in Germany has also taught their danger.

The fast long-distance coach services would lend themselves ideally to the operation of vehicles with automatic transmission systems incorporating overdrives. Engines would be of 170-190 b.h.p. and vehicle weight would be saved by the adoption of integral construction. In due course, motorway goods and passenger vehicles may be the first to be equipped with gas-turbine power units.

Tyres for Fast• Vehicles

The high-speed operation of heavy vehicles will necessitate the use of special tyres. United States manufacturers have produced tyres for fast heavy vehicles, with rayon fabric which withstands heat better than cotton. Nylon can also be used, but is expensive. To assist heat dissipation, treads are not made as thick as with normal tyres. This is no disadvantage to life. Ordinary roads, with their twists and turns—absent on motorways—create excessive abrasion and make thick treads a necessity.

Knowledge of the requirements of high-speed, heavyvehicle tyres is already possessed by makers—indeed, some ,special types embody the principles outlined. In this country, the heat problem may not be as critical as in America because of the lower average ambient tern peratures.

Conspicuous success has resulted from the construction of America's famous motorway, the 160-mile long Pennsylvania Turnpike—called a turnpike because tolls are levied on users to recoup thei1.7m. spent in building it. It was opened 12 years ago and runs between Harrisburg, the State capital, and Pittsburgh, the big coal and steel centre. The Turnpike provides four 12-ft.wide lanes and there is a 10-ft.-wide parkway down the middle. The minimum radius on curves is 1,000 ft._ The Turnpike fills a dual role. It is a major highway for heavy traffic between the two cities, and relieves other older roads, which are left for use by local people. Nearly half its cost has been collected in tolls. A fifth of the traffic is comprised of goods vehicles, which pay charges varying between three dollars and 10 dollars, according to gross weight, the maximum being 31 short tons. The largest single customer is the Greyhound coach concern.

It is now planned to extend the highway to Philadelphia, the largest city in Pennsylvania, to the east, and to the Ohio border to the west. Motorway projects have been formed in a number of other States to keep pace with Pennsylvania's advance.

Social Implications

Far-reaching social implications are involved in the establishment of a motorway system in Britain, The recent census revealed a welcome reversal of the trend in rural depopulation. Not only will motorways ease urban congestion through by-passing centres of heavy traffic and speeding up movement, but they will in themselves promote rural development.

One motorway is to link London with Newport, in South Wales, and plans have been drawn up for a suspension bridge, costing Om., to carry it across the Severn.

A more ambitious project was thought of by Isambard Brunel, who proposed a dam across the river, and this idea could be adopted instead, the motorway running over the barrage. Hydro-electric power could be generated for the South Wales industrial region and a flying-boat base established, taking advantage of the dam lake. Good road facilities for this base would be available by the very nature of the scheme, and these could serve pleasure resorts set up around the water.

Political considerations weigh in with another shoreto-shore link that would be necessary—the Channel tunnel. Although it has never reached fruition after some 50 years of existence as a mere proposal, its need will become patent with the building of first-class roads.