H h

Page 42

Page 43

Page 44

Page 47

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

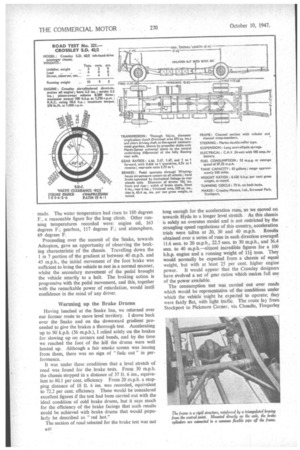

Designed to Operate at High Speed Under Arduous Overseas Conditions, the Crossley Export Single-decker Chassis, Incorporating a Number of Special Features, Represents a Triumph of British Craftsmanship. The 100 h,p. Model and its Supercharged Contemporary Are Guaranteed to Give Prolonged Service

WITH a fairly level stretch of road ahead, I watched the speedometer needle creep across the dial to 70, 80, 90, 95—and, finally, with my eyes streaming and tie flapping around my ears, we topped the 100 k.p.h. mark, equivalent to 62.5 m.p.h.

I was precariously balanced on the chassis frame, watching "Old Joe," the works tester, putting a Crossley export passenger chassis through its paces.

It might be thought that this was a freak performance, or that it incurred dangerous driving. Neither of these fears is well founded, for we made a repeat run at the maximum speed and carried out an astonishing braking test that brought the vehicle to rest in a short distance without causing any of the wheels to lock. From the beginning of the test it was apparent that this vehicle was going to provide an interesting and lively performa nce.

The chassis, a left-hand-drive model, has been designed for high-speed operation for prolonged periods under the most arduous conditions, and with a minimum of maintenance. During the road test, the chassis climbed the Snake Pass in second and third gears, and when on flat country proved itself to be an ideal vehicle for inter-urban service overseas.

Stepped-pot Pistons The Crossley 8.6-litre direct-injection oil engine, which develops 100 b.h.p. at 1,750 r.p.m., produced a clean exhaust at all loads and speeds throughout its range. As a means for promoting swirl, the piston crown incorporates a series of steps in the side of the pot combustion space, thus creating increased turbulence in the critical area. Renewable, dry-type cylinder liners are fitted to the cast-iron cylinder block, which is bolted to a cast-aluminium crankcase. The crankcase, of large proportions, is heavily ribbed to withstand the increased stresses of the high-compression engine.

Drive to the C.A.V. fuel pump is carried through a Westinghouse reciprocating compressor, both being compactly mounted on the left side of the engine. A long jackshaft, taken from a point lower down in the crankcase, drives the dynamo, which is mounted on a bracket alongside the clutch housing. Engine induction noise was noticeably absent throughout the test, being effectively reduced by the Burgess air filter and silencer.

The engine and clutch are mounted as a unit on a three-point suspension system employing Silentbloc rubber bushes. Remarkably little vibration was felt at any point in the chassis frame throughout the test. Designed for use with a full-fronted body, the radiator, supported on Metalastik mountings, is situated low down in the frame line, assuring excellent visibility. Transmission from the clutch to the gearbox is through a shaft fitted with a Hardy-Spicer front joint and Layrub rear joint, which afford a cushioned drive. The rear propellershaft transmission, divided by a centre bearing, employs Hardy-Spicer joints. .

The five-gear constant-mesh gearbox includes an over-speed ratio of 0.656 to 1, which is invaluable for the conditions under which this vehicle will be operated. The fully floating rear axle houses a centrally mounted underslung worm drive, a final reduction ratio. of 5.75 to 1 being standard for this chassis.

The pedal. linked directly to the airpressure valve, operates.: the compressed-air brakes on all four wheels

A two-stage arrangement facilitates normal braking at 3 kilogs. per sq. cm,, and at 4.5 kilogs. per sq. cm. for emergency braking; these figures correspond to approximately 42.5 lb. per sq. in. and 64 lb. per sq. in. air pressure respectively.

Every component and unit of the chassis is outstanding for its sturdiness. The side members are well sup. ported throughout their length by heavy tubular crossmembers, and even the central cross-member has been reinforced by stay brackets welded to the side members.

A Clayton automatic lubricator driven from the rear of the gearbox delivers an equal amount of oil to all the working parts of the chassis, a heavy rubber hose being used to supply the axle points.

Two concrete blocks had been bolted to the chassis as a test load, and a comfortable chair had been fitted up for the observer and photographer. Before starting the test, I was introduced to the works tester, familiarly termed " Old Joe," and then we proceeded to the weighbridge, where we found that the running weight accounted for well over 40 passengers, as well as a full-fronted body.

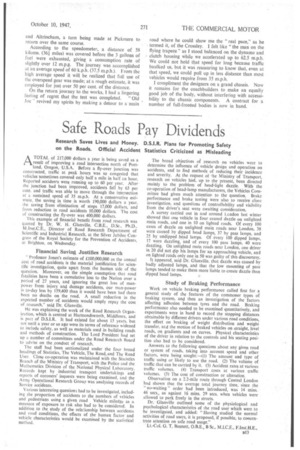

An Effective Conventional Suspension We began the test with a short diversion through Gee Cross to Hyde, so that we might try the suspension over poor road surfaces. Although neither shock absorbers nor anti-roll bars are fitted, the chassis held the road like a leech, and there was no apparent Toll on fast cornering. Our speed over this stretch of road was between 35 m.p.h. and 40 m.p.h., the works tester considering this as just a warming-up period.

It was fortunate that there were no speed traps on the main road between Hyde and Glossop, because we were constantly travelling at 50-55 m.p.h., overtaking all other traffic in sight. A minor traffic hold-up caused by badly parked vehicles in the narrower streets of Glossop gave an opportunity of proving that 8-ft. wide vehicles could reasonably be operated in this area. Continuing through Glossop towards Sheffield, a stop was made at the foot of the Snake, to take the radiator temperature, which was 158 degrees F.

At this point, the works tester was relegated to the passenger seat, while I took the wheel. Starting from rest, second and third gears were speedily engaged and held until the steeper gradient enforced a change back to second gear. Even so, maximum governed engine speed was held for the period spent in the lower gear, and it was possible to change to third gear on the lesser gradient. Of the li-mile climb up the Snake, approximately two-thirds of the distance was covered in second gear, and the remainder in third. Arriving at the peak of the hill, a check of all oil and water temperatures was made. The water temperature had risen to 180 degrees F., a reasonable figure for the long climb. Other running temperatures recorded were: engine oil, 163 degrees F.; gearbox, 117 degrees F.; and atmosphere, 69 degrees F.

Proceeding over the summit of the Snake, towards Ashopton, gave an opportunity of observing the braking characteristic of the chassis. Travelling down the 1 in 7 portion of the gradient at between 40 m.p.h. and 45 m.p.h., the initial movement of the foot brake was sufficient to bring the vehicle to rest in a normal manner, whilst the secondary movement of the pedal brought the vehicle smartly to a halt. The braking action is progressive with the pedal movement, and this, together with the remarkable power of retardation, would instil confidence in the mind of any driver.

Warming up the Brake Drums Having lunched at the Snake Inn, we returned over our former route to more level territory. I drove back over the Snake and on the downward gradient proceeded to give the brakes a thorough test. Accelerating up to 90 k.p_h_ (56 m.p.h.), I relied solely on the brakes for slowing up on corners and bends, and by the time we reached the foot of the hill the drums were well heated up. Although a fair smoke screen was issuing from them, there was no sign of fade out" in performance.

It was under these conditions that a level stretch of road was found for the brake tests. From 30 m.p.h. the chassis stopped in a distance of 37 ft. 6 ins., equivalent to 80.1 per cent. efficiency From 20 m.p.h. a stopping distance of 18 ft. 6 ins, was recorded, equivalent to 72.2 per cent. efficiency. These would be considered excellent figures if the test had been carried out with the ideal condition of cold brake drums, but it says much for the efficiency of the brake facings that such results could be achieved with brake drums that would popularly be described as "red hot."

The section of road selected for the brake test was not long enough for the acceleration runs, so we moved on towards Hyde to a longer level stretch. As this chassis is solely an overseas model and is not restricted by the strangling speed regulations of this country, acceleration trials were taken at 20, 30 and 40 m.p.h. Results obtained over a series of runs in each direction averaged 11.6 secs. to 20 m.p.h., 22.5 secs. to 30 m.p.h., and 36.4 secs. to 40 m.p.h.—almost incredible figures for a 100 b.h.p. engine and a running weight of Hi tons. They would normally be expected from a chassis of equal weight, but with at least 25 per cent. higher engine power. It would appear that the Crossley designers have evolved a set of gear ratios which makes full use of the power available. The consumption test was carried out over roads which would be representative of the conditions under which the vehicle might be expected to operate; they were fairly flat, with light traffic. The route lay from Stockport to Pic.kmere Corner, via Cheadle, Timperley

and Altrincham, a turn being made at Pickrnere to t et urn over the same course.

According to the speedometer, a distance of 58 k Rms. (361 miles) was covered before the 3 gallons of fuel were exhausted, giving a consumption rate of slightly over 12 m.p.g. The journey was accomplished at art average speed of 60 k.p.h. (37.5 m.p.h.). From the high average speed it will be realized that full use of the overspeed gear was made; at a rough estimate, it was employed for just over 50 per cent. of the distance.

On the return journey to the works, I had a lingering feeling of regret that the test was completed. "Old Joe' revived my spirits by making a detour to a main

road where he could show me the "real pace," as he termed it, of the Crossley. I felt like "the man on the flying trapeze" as I stood balanced on the dynamo and clutch housing while we accelerated up to 62.5 m.p.h. We could not hold that speed for long because traffic baulked us, but it was reassuring to know that; even at that speed, we could pull up in less distance than most vehicles would require from 35 m.p.h.

I compliment the designers on a grand chassis. Now it remains for the coachbuilders to make an equally good job of the body, without interfering with accessibility to the chassis components. A contract for a number of full-fronted bodies is now in hand.