HEART OF THE SOUTH

Page 54

Page 55

Page 56

Page 57

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

Big, beautiful and bursting with potential...

Oliver Dixon watches the rebirth of Brazil and its automotive industry.

Rernember Brazil? Once upon a time, it was the great white hope of the globalising hordes, the cornerstone of South American trade and an all-round good thing for an automotive industry looking for new frontiers to cross and new revenues to accrue.

And then it fizzled. In a bout of premillenial jitters, the Brazilian economy headed south,led by a national debt that, at one point, accounted for more than 50% of GDP Devaluations, emergency taxes and a complete fiscal hoo-hah saw the place through Y2K, and to a meeting with the subsequent collapse of Argentina. By this time, China and India were today's specials, the North Amercian Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) appeared to be doomed, everyone was losing their shirt in the former Soviet Union and South America appeared to have become but a fond memory. Just another day in Automotivesville.

All very unpleasant. And then to compound the rn isery, elections in 2002 saw one Luiz lnacio da Silva. a left-winger with little by way of government experience win the popular vote and become president.There followed a rush on adjectives as financial doomsayers the world over fell over themselves in the race to consign what was left of the Brazilian economy to history, and everyone sat back and awaited the rapture.

Which, despite a couple of after-jitters is still to arrive. Brazil has emerged from the economic black hole of the late 1990's, and da Silva — Lula's — policy of fiduciary tough love seems to be paying off, with no industry seeming to have benefited more than the automotive sector. In 2004, Brazilian vehicle output reached 2.2 million units, beating the previous record of two million, set back in 1997. In terms relative to the current emerging favourites. this compares with the 4.5 million units produced in China, and the 1.5 million turned out in India.

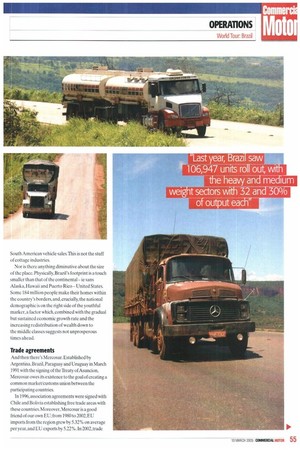

Production leapt year on year by 20.7%, while exports soared by almost 52%, with 2004 seeing more than $8.2bn worth of Brazilian automotive production crossing the country's borders.To date, 27 automotive manufacturers are up and doing in Brazil, employing almost 170,000 people, and with an annual value of over $18bn.This represents 11% of the Brazilian Gross Domestic Product, and, in broader terms, the Brazilian auto sector now accounts for 80% of all South American vehicle sales.This is not the stuff of cottage industries.

Nor is there anything diminutive about the size of the place. Physically, Brazil's footprint is a touch smaller than that of the continental le sans Alaska, Hawaii and Puerto Rico -United States. Some 184 million people make their homes within the country's borders, and, crucially, the national demographic is on the right side of the youthful marker, a factor which, combined with the gradual but sustained economic growth rate and the increasing redistribution of wealth down to the middle classes suggests not unprosperous times ahead.

Trade agreements

And then there's Mercosur. Established by Argentina.Brazil,Paraguay and Uruguay in March 1991 with the signing of the Treaty of Asuncion, Mercosur owes its existence to the goal of creating a common market/customs union between the participating countries.

In 1996, association agreements were signed with Chile and Bolivia establishing free trade areas with these countries. Moreover, Mercosur is a good friend of our own EU;from 1980 to 2002,EU imports from the region grew by 5.32% on average per year, and EU exports by 5.22%.1n 2002, trade with Mercosur represented 2.44% of total EU imports and 1.83% of total EU exports, making it Europe's second biggest import partner, and fifth biggest export recipient.

Which, in a roundabout way, explains why European automotive companies are pretty taken with the place. You might think that NAFTA would have put a colonising arm around the nascent Mercosur's shoulders: you'd be wrong. For commercial vehicles, think Europe.

As witnessed by a closer look at the 2004 truck sales figures for Brazil. Last year, the country saw 106,947 units roll off its production lines, with the heavy and medium-weight sectors vying for dominance at around 32 and 30% of output respectively. Market leadership sits with Scania at the heavy end. MercedesBenz in the middle and VW at the light.

But these numbers don't tell the whole story. Upping its market share by 40% during 2004, lveco can lay claim to —at the very least —a special achievement ribbon. With heavy sales advancing in excess of 245% from 2003 to 2004, and light vehicles putting on a 50% rise, there's obviously something happening in the Italian quarter. Much of the reason for this lies in a combination of bricks and mortar and tough decisions.

Iveco has a track record in South America that goes back some 30 years. Currently, the company operates three manufacturing locations — at Cordoba in Argentina, La Victoria, inVenezuela and Sete Lagoas in Minas Gerais, Brazil, Backing up these production sites is a network of 89 sales and 145 service points through South and Central America. In addition, Iveco sub-brands — Astra and Iveco Motors — also boast a sales and service network throughout the territory.

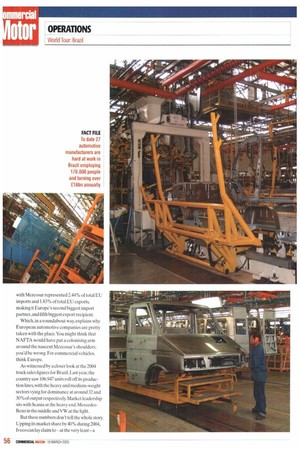

But it is Sete Lagoas that is the principal focus of the company's operations within the area. Representing a $240 million investment, the plant came on stream in 2000, and has had a considerable impact upon the area, with what amounts to a supplier park developing alongside the main 700,000m2 facility, which, in addition to the production of Iveco truck product, is also charged with the production of both Daily vans and Fiat Ducato LCVs. In addition to the 5,000m2line turning out Eurotech and Euro-cargo models, there's also a dedicated 7,000m2 plant producing engines, important given that Brazil — and, one assumes, the rest of the region — is looking to EU emissions legislation as its future guide.

Cheap loans

EuroTech seems a bit old — whither Stralis? The answer lies in finame. What now? In other words a bit of Brazilian self help. Fmame is a government-backed scheme in which truck operators can benefit from vastly improved borrowing terms as long as their loan finances a product with a minimum 60% local build content.

Iveco is currently building Stralis models in Argentina, and,as such,these do not qualify for the tax break. In time.Stralis production will shift to Sete Lagoas, but there is an obvious issue in going from zero to 60% local content in one hit. Hence the longevity of the EuroTech.

But, in truth, in its slightly tropicalised form, the EuroTech is a pretty fair match for Brazilian operating conditions.These range from good road to what road, and encompass just about every terrain known to man. From what we were able to see in terms of GVW, weights appear nominal, and the absence of the ministry and its attendant weighbridges suggest that many Brazilian operators work on the basis of It's loaded when it's full'.The EuroTech — which is here, to all intents and purposes, a EuroTrakker — is about on the mark for this sort of work.

Allgood stuff, but what of the future? Here we head into the realms of definition. Brazil is perceived by many as an emerging market. That seems a pretty harsh judgement. Sao Paolo is not without its rougher areas, but it's not without its skyscrapers and big number investors either.This is not darkest back of beyond, and you can find a tube of Colgate without looking too hard. Emerging seems to understate the place, while Emerged reduces somewhat its potential for the future. And,moreover, if Mercosur is brought into the equation, then the numbers really do begin to stack up. Peeking through the dust of years of iffy politics and muppet economics is an emerging middle class, hungry for goods and infrastructure. And, despite what Paul Theroux may have had to say, railways are in the minority here, and so consumer demand is going to be sated, inevitably, by the CV.

A popular misconception today seems lobe that any non-first world country is, by definition, a maquiladora, a place where the first world gets to build its stuff on the cheap.That Brazil has no shortage of domestic and regional export demand suggests that applying this sobriquet would be daft.

Which, in the final analysis, suggests that lveco has played a sharp hand here. Sete Lagoas offers a huge amount of potential for the years to come.The existence of meaningful car parking spaces all around the facility suggests that expansion isn't likely to be a problem, and the company's willingness to train up the local population can only pay dividends, both in terms of productivity and workplace loyalty.

As Brazil, Mercosur and the rest of the South American continent continue to move forward, Iveco finds itself in the not-unhappy position of being able to meet domestic and regional demand with what amounts to a domestic product.

Planning the play

You want to be a global player, you've got to play across the globe. Simple enough. But structuring one's game plan in such a way that it emerges from within each distinct territory, as opposed to a one-size-fits-all approach, is not so easy. It takes time, and not a small amount of effort. Iveco has gone about its business in South America using this bottom up approach, and, on the basis of 2004, it's an approach that seems to be working.

That there's never complete certainty in global economic and national development is a given. But work on the basis that Brazil has an increasingly mature economy, and, as importantly, an increasingly stable political climate, and you'd be hard pressed not to justify at least an each way punt on this place working out pretty sweetly.