COMPARATIVE TEST OF THE SCAMMELL OIL AND PETROL RIVEN 1 2-TONNERS

Page 50

Page 51

Page 52

Page 53

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

Road Test No. 1 38

The Same Rigid Six-wheeler, Propelled First by a Gardner Six cylindered Oil Engine and Later by a Scammell Fourcylindered Petrol Engine, Subjected to Identical Tests Interesting Results of an Exhaustive Series of Tests Provide Informative and Accurate Data for Judging the Respective Advantages of the Two Types

OUR road test this week is of' exceptional interest, as it enables a clear comparison to be made between the performances of an oil engine and a petrol engine stalled in the same chassis and tested under almost identical conditions. Although conducted on separate occasions, the consumption tests were carried out over the same route, and

the acceleration tests in the same locality ; furthermore, the vehicle, in each case, was handled by the same driver.

In addition to its value for purposes of comparison, this road test also has much of interest because it concerns a Scammell 12-ton rigid six-wheeler, a chassis which incorporates certain unusual features, is one of the largest vehicles of its kind in general iLse and ranks high amongst British commercial vehicles.

Before describing the performance, it may be as well, briefly, to run through the main features of the chassis. The alternative power .units available are the Gardner six-cylindered LW-type compression-ignifion engine, and the Scanamell four-cylindered petrol engine. The clutch 3332 used for both tests was of the single-plate type, although, normally, the petrol engine transmits its power through a clutch of the inverted-cone type. Both are provided with clutch stops.

Behind the clutch, a separate gearbox is mounted. The standard box has four speeds, but a five-speed box is available and was installed in the chassis we tested. A shaft having a universal coupling at each end conveys the drive to a countershaft through a spiralbevel and differential gear. Thence sprockets and Duplex 14-in. pitch chains take it on to the forward wheels of the bogie. The overall ratio of the Scammelt" vehicle which we tested was 7.8 to 1.

The ratios provided by the box and each reduction gear are given in the accompanying specification panel, but it is worthy of note that the driving driving sprockets can be Changed quickly and easily. BY this simple means the overall ratio can be altered through a wide range to suit special operating condi tions. The standard driven sprocket has 52 teeth, and the most generally used driving sprockets have 21, 22 or 23 teeth. Sprockets with numbers of teeth from 17 to 24, however, are available. The work of changing a sprocket involves removing eight screws, pulling off the sprocket, fitting another one, and adding or removing the required number of links to or from the chain.

The rear bogie suspension consists of a pair of inverted semi-elliptic springs. Each is mounted at its centre on a trunnion, about which it can oscillate. The front end bears on a roller mounted just below the forward axle, whilst the rear is bolted to a chair on the rear axle. The forward axle is located by a pair of adjustable radius rods.Diagonally -split central spring brackets give a tight grip.

The front springs, also semi-elliptics, are anchored to the frame at their rear ends, whilst their forward ends work between rollers in housings mounted on the dumbirons. This arrangement entirely obviates the use of shackles in the suspension. Zerk grease nipples are fitted to all parts requiring lubrication.

The policy of Seammell Lorries, Ltd., is to rely solely upon the muscular effort of the driver,for the operation of the brakes. Opinions. 'differ as to the advisability of pursuing this course, or of employing some systenf of power servo. We write from actual experienee, however, when we state that the Scamme11 system of bra 'lug is efficacious, and our personal muscular strength is probably many degrees inferior to that of the man whose job it is regularly to pilot gross weights of 19 tons on the road.

Our intimate acquaintance with the brakes was formed while negotiating the intricate network of roads on the outskirts of Watford, when returning to the Scammell works on the west side of the town from the direction of Bushey. There was much heavy traffic at the time, whilst there are numerous bills, narrow roads, and many corners in that district.

The system is for the pedal to apply the frontwheel brakes and a transmission brake, which consists of a pair of expanding shoes in a deeply ribbed drum immediately behind the gearbox. The hand lever operates separate brakes on the four bogie wheels. The maker states that the transmission brake receives 60 per cent, and the front wheels 40 per cent, of the total effective pedal pressure.

Our braking graph shows the hand brake to afford slightly superior retardation, and when at the wheel ourselves we found it, if not more effective, certainly pleasanter to use, owing to a slight juddering B34 caused by vigorous, application of the pedal. The lever is situated so that one can get a really good pull on it ; together, they bring 19 tons of moving weight to rest in a manner which inspires confidence.

With muscularly applied brakes, it is ' comforting to know that they cannot let one down through the stoppage of the engine or some improbable failure of a servo mechanism, but it is paid for by the lack of that powerful retardation produced by a gentle pressure of the foot, such as is afforded • by a first-class servo system.

Our first test was made with the Gardner engine installed, the vehicle tieing a platform-type lorry. Carrying a load of just under 12 tons, it sealed, including the driver, observer, a tank full of fuel, etc., exactly 19 tons gross weight, the legal limit for a six-wheeler. This figure was verified by us prior to setting out.

The oil-consumption test consisted of a run from the works at Watford to Aylesbury and back. The route is moderately hilly, as it follows an undulating valley in the Chiltern Hills. It includes the northern outskirts of Watford, the crowded main _ street of l3erkhamsted, the climb through the centre of Trieg, and

a part of Aylesbury. The road is narrower than the average English main road, and passes through several villages besides the towns named. The oourse chosen may, therefore, be regarded as a fair one for a consumption test, erring, if anything, on the exacting side.

That the return journey of 49.2 miles was made at an average speed approaching the legal limit speaks highly for the general performance of the machine, and this includes four brief stops caused by traffic hold-up s. Four gallons and five pints of fuel were consumed ; that is to say 10.64 m.p.g. A hilt on the outward .journey, between Berkhamsted and Tring, 'brought us down to fourth gear for about 0.1 mile, and the climb from Aylesbury to the high ground west of Tring, on the return, called for some third-gear work.

Our petrol-consumption test over the same route was made with the Scamme11 four-cylindered engine. The mileage recorder showed the distance covered to be identical with the previous run on oil. Six gallons five and a quarter pints of petrol were consumed, equivalent to a consumption of 7.39 m.p.g.

The bill beyond Berkhamsted on the outward journey demanded third gear, and this ratio was used in Tring. On the return journey, about half a mile of the climb towards Tring required third gear, whilst the Majority of the remainder was accomplished int:fourth gear.

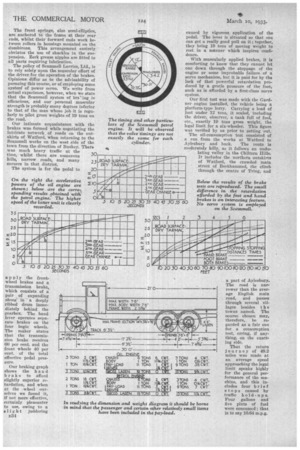

The Watford by-pass provided an almost level stretch for our acceleration and braking tests. The former were made in both directions and the curves were plotted from the mean figures obtained. There is no reason why the two tests should not be suitable for a direct comparison to be made between the 7-litre Scamme11, and the 84-litre Gardner engines, the conditions obtaining being similar, except for the fact that the atmospheric temperature on the latter occasion was considerably lower.

On oil, the ascent of Brockley Hill from the north, with a standing start from the by-pass crossing, occupied 1 min. 17, secs. Starting in second gear, third and then fourth were engaged, third re-engaged on the steepest portion, and a change up to fourth made just below the summit. On petrol, the time was 2 mins. 21) sees., and it was found necessary to drop into second where the gradient stiffens.

From the south, the latter half of the gradual approach was traversed on oil fuel in fourth, the speed dropping from 15 m.p.h. to 11 m.p.h. at the old gradient sign at the foot of the steep portion; third was there engaged, and then second, the lowest speed reached being about 4 m.p.h. The time taken from the sign to the water trough at the top was 2 mills. 10 seca.

,Later, with the petrol engine, the same ascent was made in equal time. At a point about 150 yards before the old gradient sign, our speed having dropped to 12 m.p.h., third was engaged. The 1-in-Si portion brought us down to second, in which gear we climbed steadily at about 6 m.p.h., without signs of distress.

Prior to the hill-climbing tests, on both occasions, part of the radiator had been blanked off, and the. temperatures at the foot of the first hill were 190 degrees F. and 170 degrees F. on oil and petrol respectively. The radiator shield was removed, however, at the foot of the hill, with the result that the temperature after the final climbs, in both cases, was no more than 195 degrees F. From the top we allowed the vehicle to run backwarda to the steepest portion (about 1 in 8i), where restarts were made on oil and on petroL These were accomplished with ease, in second gear, and, with the oil engine, the heavy vehicle continued to ascend steadily in this gear with the driver's foot removed from the accelerator pedal and the throttle in the tick-over position.

On neither fuel did the gradient demand the use of the emergency low gear, but it must be borne in mind that this chassis is built to carry 14 tons, giving a gross weight of over 21 tons.

The steering gear of this Scammell vehicle is of the Merles type, operating reversed Elliott-type swivels. Its self-centring action is more than usually pronounced_a great asset to the driver when straightening out after rounding a corner; nor is this advantage offset by any undue heaviness when putting the lock on.

Another item to ease the driver's lot is to be found in the ingenious mechanism that controls the fuel pump, or throttle valve. When the accelerator pedal is fully depressed, one of the operating rods comes just on dead centre with one arm of the bell-crank to which it is hinged ; thus no reaction from the powerful return spring is transmitted to the pedal, so long as it is fully depressed. A stop prevents the mechanism from passing dead centre, and engine vibration ensures that the pedal returns, One of our pictures shows the spare-wheel carrier in action. The system needs little description, being simply a winch rotated by a handle from the side of the chassis and arranged to wind up a cable to which the wheel is hooked and by which it is normally held securely against the frame members .

Summing up our impressions of these most interesting -comparative tests, we were first struck by the superior liveliness of the petrol engine. It was, of course, ungoverned, and a study of the acceleration curves reveals how every change was made at higher speed. On the climb of Brockley Hill from the south, this feature enabled a higher speed to be maintained in second gear, which compensated for the fact that the distance the machine was able to travel in third was markedly less with petrol.

The longer climb, from the north, demonstrated well the superiority of the oil-engine in "hanging on" and continning to develop its torque at low speeds.

But, perhaps, the factors of maximum speed and fuel consumption are of greatest moment.

Whilst the oiler has a superiority of 3.2 m.p.g.-disregarding the fact that the fuel is cheaper-in the matter of maximum speed, it falls short of the petrol-driven model (which costs less to buy) by 6 m.p.h. In many respects the oiler would have performed better with a higher gear.