Haw Capital Appreciation on the Sale of a Used Vehicle

Page 55

Page 56

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

at More than its Cost Price Affects Income Tax. A Disappointment for an Optimist

Coach Sale Profits

and Income Tax WHEN I read the letter, part of which is set out below, I could not make up my mind whether the writer was trying to pull my leg, trying to make me pull the leg of the readers of this journal, or whether he was actually leading himself up the garden. I did agree, however, that the point he raised was an interesting one. I Will refer to my correspondent, who wishes to remain incognito, as Mr. Optimist. He writes:—

" Is your enlightened contributor able to advise as to -the financial disadvantage of a user selling a vehicle at a figure greater than its cost? The advantage is too obvious— it results in a capital appreciation which, as such, is not taxable.

"I regard that benefit as of no importance, because at the moment 1 am not a seller, but am trying to be a buyer, and, failing to convince myself that there is any prospect of ultimate profit in paying one-third more than list price for a vehicle one year old, I am trying to convince the sellers that by selling at this profit they are in fact losing money.

"I have got as far as reckoning that on a coach costing new £2,000, an initial allowance of £400 is made (normally worth £180 of saved taxation) and further depreciation of a somewhat similar percentage is allowed, presumably worth a similar sum, for the first year. Rut when a sale is effected there is a balancing charge, and I have-been trying to prove that this, if the sale price be above its book value, negatives the initial and depreciation allowances and that, in fact, an owner is better off financially, in the long run, if he sells at a loss instead of at a profit."

Conditions Before 1945

The first thing to do is to make the position quite clear as regards income-tax allowances on motor vehicles, particularly coaches. Moreover, to make the story complete, must go back a little in history and deal first with conditions before the 1945 Income Tax Act came into operation.

Then the allowances for depreciation and wear and tear which an operator could seek were as set out in Table I. Each year he was allowed 20 per cent, per annum on the falling value of the vehicle, plus one-fifth of that 20 per cent.

Curiously enough, however, the full allowance was not deducted each year from the price of the vehicle in order to arrive at its value for calculation of income-tax allowance in the next year, but only 20 per cent. Thus, as in Table I, a vehicle which originally cost £2,000 was subject to an allowance in the first year of 20 per cent., that is £400, plus one-fifth of £400, which is £80, a total of £480. For the second year, however, the value of the vehicle on which these allowances were calculated was not £2,000 less the total allowance, £480, but only £2,000 less £400.

There is a time, however, at which the total allowance is taken into consideration, and that is when, for a reason which will develop soon in this article, it is necessary to state the net value of the vehicle. In those circumstances the total of allowances made, including the one-fifth 35

well as the 20 per cent., must be deducted from the original sum. That net value comes into consideration when the owner of the vehicle sells it and wishes to gain some credit from the income-tax authorities if his selling price be less than that net value.

It is necessary to consider in this connection situations, both relating to the cas: of a man who is about to sell his vehicle after having had it in use for a period of years. These are (a) when the price obtained is less than the figure at which the vehicle stands in his income-tax records, and (b) if the selling price be more than that amount. Assume that the position is as set out in Table I. that is to say, all the transactions take place before 1944. Suppose that the sale is to be effected at the end of the fourth year of use. The net value of.that vehicle, as the income-tax authorities would regard it, is the original cost less the total of those allowances on which rebate of income tax has been given, that is to say, £2,000 less £1,417, which is £583.

Rebate of Tax

First let us take it that the owner was able to obtain only £283 for the vehicle, according to condition (a) above. Then, provided that the coach is to be replaced by another to be employed similarly (an essential condition), he can enter the difference of £300 in his return of income tax for that year as a business expense and may expect to be allowed rebate of tax accordingly.

Suppose, according-to condition (b), the operator sold the vehicle in the early war years, when coaches were at a premium. He might well have got £1,800 for it, thus showing a capital appreciation of £1,800 less £583, which is £1,217. He would have to make a return of that £1,800 and pay tax on £1,417 of it, that being the sum total of allowances made to him during the four years in which he has operated the vehicle: the rest would be regarded as "capital appreciation" and would not be subject to tax. Here, again, another proviso must apply—that the operator was not normally engaged in the buying and selling of coaches as a business.

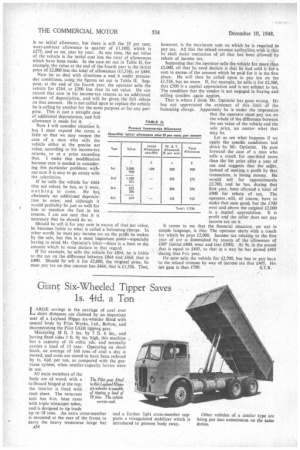

Now conditions arc different in a good many ways. In the first place, the method of assessing income-tax allowances has changed. Instead of there being regular depreciation and wear-and-tehr allowances of 20 per cent., plus one-fifth, the purchaser of a new or used vehicle is allowed to set off as business expense in his return of earnings and expenditure, first, what is called the initial allowance, which is 20 per cent, or one-fifth of the price paid for the vehicle, and then, year by year, 25 per cent. of the declining value of the vehicle, as set out in Table II.

Here, again, I have assumed an initial purchase price of £2,000. During the first year there is the initial allowance of one-fifth (£400), plus wear-and-tear allowance of 25 per cent. (£500), ,so that the total allowance in the first year is £900. The value of the vehicle for the second year is, however, reduced by the whole of that allowance of £900, becoming thus £1,100. In the second year, of course, there is no initial allowance, but there is still the 25 per cent. wear-and-tear allowance ta quarter of L1,1001, which is £275, and so on, year by year. At any time, the net value of the vehicle is the initial cost less the total of allowances which have been made. In the case set out in Table II, for example, the value at the end of the fourth year is the initial price of £2,000 less the total of allowances (f1,536), or £464.

Now let us deal with situations a and b under presentday conditions, using the figures set out in Table II. Suppose, at the end of the fourth year, the operator sells the vehicle for £264, or £200 less than its net value. He can record that sum in his income-tax returns as an additional amount of depreciation, and will be given. the full rebate on that amount. He is not called upon to replace the vehicle he is selling by another for the same purpose or for any purpose. This is just a straight case of additional depreciation, and full allowance is made for it.

Now I will consider situation b, but I must expand the terms a little so that we may reopen the case of a man who sells the vehicle either at the precise net value, according to his income-tax returns, or at a price exceeding that. I make that modification because care is needed in considering this particular problem; without care it is easy to go astray with the calculation.

If he 'sells the vehicle for £464 (the net value), he has, as it were, nothing to come. He has obviously no additional depreciation to enter, and although it would probably be just as well for him to mention the fact, in his returns, I am not sure that it is necessary that he should do so.

Should he sell it. for any sum in excess of that net value, he becomes liable to what is called a balancing charge. In other words, he must pay income tax on the profit he makes by the sale, but this is a most important point—especially having in mind Mr. Optimist's letter—there is a limit to the amount which he must declare in that regard. .

If for example, he sells the vehicle for £864, he is liable to the tax on the difference. between £864 and £464, that is £400. Should he sell it for £2,000, the Original price, he must pay tax on that amount less £464, that is £1,536. That,

Year Value

1st 2.000

900 2nd 1,100

27.5 3rd 825

206 40 619

however, is the maximum sum on which he is required to pay tax. All that the inland revenue authorities wish is that he shall make restitution of all that has been allowed by rebate of income tax.

Supposing that the operator sells the vehicle for more than £2,000, all that he need declare is that he had sold it for a sum in excess of the amount which he paid for it in the first place. He will then be called upon to pay tax on the £1,536, but no more. if, for example, he sells it for £2.500, that £500 is a capital appreciation and is not subject to tax. The condition that the vendor is not engaged in buying and selling coaches again applies.

That is where I think Mr. Optimist has gone wrong. He has not appreciated the existence of this limit of the balancing charge. Apparently he is under the impression that the operator must pay tax on the whole of the difference between the net value of the vehicle and the sale price, no matter what that may be.

Let us see what happens if we apply the specific conditions laid down by Mr. Optimist. He puts forward the case of a man who sells a coach for one-third more than the list price after a year of use and suggests that the seller, instead of making a profit by that transaction, is losing money. He would sell for approximately £2,700, and he has, during that first year, been allowed, a totalof £900 for rebate of tax. The operator,will, of course, have to make that sum good, but the £700

It seems to me that the financial situation, set out in simple language, is this: The operator starts with a coach for which he pays £2,000. Income tax relating to the first year of use is diminished by reason of the allowance of 190(' (initial £400, wear and tear L500). At 9s. in the pound that is equal to £405, so that in a way he has gained £405 during that frst. year. Pe now sells the vehicle for 52,700, but has to pay ba;:k to the inland revenue by way of income tax that £405. His net gain is thus £700. S.T.R.

Total: 1.536 over and above the original £2,000 is a capital appreciation. It is profit and the seller does not pay income tax on it.