SAFETY

Page 42

Page 43

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

Nearly 200 people perished in the Hera of Free Enterprisedisaster; another 85 died in the Estonia at Hagan looks at developments in RO-R0 technology and asks if getting that consignment

overseas is as safe as you'd like to thin

Roger Broomfield knows the only reason he is alive today is his own instinct for survival and a powerful pair of shoulders. Without either, he would surely have perished along with the 193 others who lost their lives on 6 March 1987 when the Herald of Free

Enterprise sank off Zeebrugge.

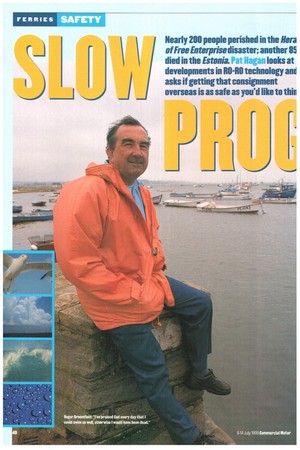

Broomfield, a veteran of the haulage business, was in a cabin below the waterline when the lights went out, signalling the beginning of one of the worst peacetime disasters in maritime history. Underwater and in pitch blackness, he somehow made his way to safety in what he now readily admits was nothing short of a miracle. "I've praised God every day since that I could swim so well, otherwise I would have been dead," says the 57-year-old driver from Poole in Dorset.

Broomfield, who had been returning from Germany with a consignment of chemical waste products, was one of the last survivors to be rescued from the stricken ferry after being stranded for almost seven hours. Other drivers were not so lucky. They were among the victims of a tragedy which struck horror into the hearts of millions and focused attention on the dangers of RO-RO ferries.

But 12 years on, the controversy refuses to go away. Although safety procedures aboard many ferry routes have been significantly tightened up, opinions remain divided over whether enough has been done to ensure that the design of ferries is as safe as it could be.

In the years following the disaster a debate raged over what measures were needed to prevent it happening again. Ferry operators argued that it would be unfair to impose mandatory, costly changes to the design of their vessels when the evidence was that the Herald of Free Enterprise had sunk because of human error. In response, MPs on the House of Commons Transport Select Committee demanded that changes be made so ferries remained upright for at least two hours after an accident—instead of 30 minutes—to allow evacuation.

The discussions dragged on and were only given impetus by another seafaring tragedy of such magnitude that it eclipsed even the Herald tragedy. In September 1994 the ferry Estonia went down in the Baltic Sea with the loss of more than 850 lives.

An official report revealed that design faults and an incompetent crew contributed to the disaster, in which 13ft waves ripped off the vessel's visor-style bow door, allowing water to pour onto the vehicle deck.

The accident happened in the early morning when most passengers were asleep and the ship sank so quickly, plunging hundreds of feet to the bottom of the sea, that the majority of them had no chance of escape.

The combined effect of the two tragedies was to throw into question the whole concept of RO-RO ferries. Even though such vessels had transformed international haulage, and had been the sole form of crossChannel travel for 13ritish drivers for years, suddenly there was a perception that passengers might be taking their lives in their hands every time they boarded one.

A panel of experts was set up by the International Maritime Organisation to examine the safety of RO-R0s. It looked at whether the fitting of bulkheads to the car deck would help the ship survive an accident. And it also scrutinised all the procedures involved in running ferries— from what operational guidelines were in place for sailing in rough weather, to how multinational crews communicated

After years of deliberation the first of a series of new measures took effect on i January this year to prevent a repeat of the confusion which arose in previous tragedies because ferry companies had little or no idea who was on board their ships.

Trageckes

Incredibly, until these tragedies forced a reassessment of the way ferry firms worked, there was no obligation for them to even count the number of passengers sailing on their ships.

Under amendments made to the International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea, details of all passengers—including name and gender, and whether they are an adult, a child or an infant— must now be recorded for searchand-rescue purposes. These details are kept ashore and immediately handed to the emergency services in the event of a crisis.

Tough new measures demanding better training for ferry staff have also come into effect. As well as crisis management, crews must now be trained in dealing with passenger safety, and handling various aspects of human behaviour.

In terms of design, new regulations mean that all RO-RO ferries built after July 1998 must be equipped with fast rescue boats

and a means of recovering survivors from the water. They must also be equipped with a helicopter pick-up area, while vessels longer than I3OM built after July this year must have a helicopter landing area.

These measures have certainly gone some way to improving the passengers' chances of survival in the event of another serious incident. But it is questionable whether the changes made so far will do much to prevent another major tragedy. In May, a survey carried out by a major international motoring body showed safety procedures on one in four RO-RO ferries were rated as either "poor" or "very poor".

The Alliance Internationale de Tourisme and Federation Internationale de Cautomobilea European umbrella group of motoring organisations—went so far as to warn that travellers were putting their lives at risk by using the ferries in question.

They tested 23 ships in the North Sea, the English Channel, the Baltic and the Mediterranean and found a wide range of safety deficiencies. Only one ship was classed as "very good", although those operating on the main UK routes were generally safe.

Dangerous faults included life-rafts tied up with ropes, rotten life vests with night lights and whistles missing, and rusty, worn or unserviced firefighting equipment. They even found one vessel with a bow door that was not watertight.

That fact alone is enough to worry Herald of Free Enterprise survivor Roger Broomfield. He has no problem using ferries now but admits to being troubled by the fact that the one thing that has not yet changed is the fundamental design of RO-RO ferries.

"It has to be said that you need very little water on the car deck of a RO-RO ferry to make it unstable," he points out. "And nobody will ever convince me that ships have not crossed the Channel with their bow doors open all the way."