Collecting the Farmers' Milk and Delivering it to the Dairies.

Page 101

Page 102

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

Some Advice to Contractors who are Considering Entering this Sphere of the Haulage Business

Problems of the

HAULIER and CARRIER THIS issue of The Commercial Motor is of particular interest to all those who are engaged in the pursuit of agriculture in one or other of Its many departments, and I am, therefore, proposing, this week, to digress. from the series of articles on problems appertaining to the use of tractors and trailers, so that I may consider a subject appropriate to this issue. I -have chosen milk haulage as' being one of general interest.

There is plenty of good and reasonably profitable business for hauliers in the transport of milk. It is a department of the haulage industry which, however, involves certain special conditions, and as these directly affect the profit to be made, it is important that they should be properly understood and in nowise overlooked.

Contracts Available All Over theCountry.

First I will deal with the kind of business that is offered. So far as readers of these articles are concerned, practically all milk is carried in churns. Contracts for the transport of these churns are available all over the country for all distances up to 100 miles each way. There is the conveyance from farm to station, from station to dairy, direct from farm to dairy as well as from farm to collecting depot of either a dairy or milk-using factory. The carriage of bottled milk or of milk in tanks is usually performed by the dairy companies in their own vehicles.

Churns are of three sizes. There are cylindrical containers for 10 gallons and 12 gallons, and the olderfashioned and more popular conical type holding 17 gallons. The weight of a full churn is 1 cwt., 11 cwt. and 2 cwt., according to the capacity.

The haulier's difficulty with the ordinary type of platform lorry is to find sufficient room for the precise number of churns needed to complete a load up to the capacity of his vehicle. To overcome this difficulty a supplementary platform, capable of holding sufficient extra churns to enable a full load to be carried, is fitted immediately behind the driver's seat.

A Typical Body Arrangement.

As typical of the arrangements that are made after this fashion, I can quote the case of a 5-ton lorry designed to carry 75 12-gallon cylindrical churns. The dimensions of the platform of the lorry were 14 ft. 3 ins. by 6 ft. 6 ins., and this was sufficient to accommodate only 55 of the churns. A supplementary platform was, therefore, built above, it •being 5 ft. 3 ins. deep from the back of the driver's seat and 2 ft. 8 ins. above the level of the main loading space. That sufficed to enable the load to be completed. Another point to note while on the question of bodywork is that there is liability for empty churns at least to be rather noisy, and, as all my readers know— some of them to their cost—a noisy load may easily involve a severe fine. It is, therefore, customary to line the chains or supporting boards around a milk lorry with rubber, so as to deaden the noise. A contract for the conveyance of milk usually involves working seven days per week, 52 weeks per year. It will be obvious that in entering into such a contract the haulier must have in mind the need for occasionally providing a spare vehicle, when his own is out of commission, and he must reckon on having to pay overtime or extra wages to a second man for some days every week.

Quotations are usually asked for per gallon, although occasionally the contract is at a given price per churn. Invariably the haulier is expected to return the empty churns at the price quoted for the milk. There are no set figures. It is up to each contractor to consider carefully every proposition which is put to him. Most of' the milk-carrying hauliers with whom I am in touch are obtaining fair prices.

On the other hand, there are one or two who would be better out of the business. If I have any hesitation in writing this article, it is the fear that I may encourage participation by that type of contractor who regards the cutting of rates as the most satisfactory method of entering into competition with a rival.

In quoting the following examples of what is already being done, just. to show what class of business milkcarrying is, I should like to impress upon new readers, and particularly those who are thinking of taking up milk cartage, that they should submit prospective contracts to me before they enter into them.

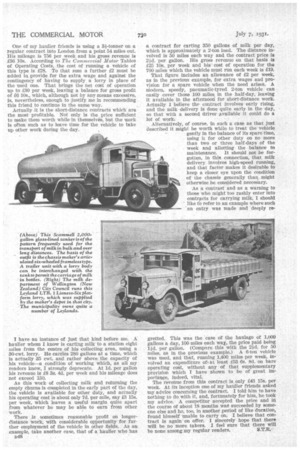

One of my haulier friends is using a 3i-tonner on a regular contract into London from a point 54 miles out. His mileage is 756 Per week and his gross revenue is £36 10s. According to The Commercial Motor Tables of Operating Costs, the cost of running a vehicle of this type is £28. To that sum a further a must be added to provide for the extra wage and against the contingency of having to supply a lorry in place of the used one. That brings the net cost of operation up to £30 per week, leaving a balance for gross profit of £6 10s., which, although not by any means excessive, is, nevertheless, enough to justify me in recommending this friend to continue in the same way. Actually it is the short-distance contracts which are the most. profitable. Not only is the price sufficient to make them worth while in themselves, but the work is often such as to leave time for the vehicle to take up other work during the day.

I have an instance of just that kind before me. A haulier whom I know is carting milk to a station eight miles from the centre of his collecting area, using a 30-cwt. lorry. He carries 280 gallons at a time, which is actually 35 cwt, and rather above the capacity of his vehiclea condition of working which, as all my readers know, I strongly deprecate. At 1.d. per gallon his revenue is £8 3s. 4d. per week and his mileage does not exceed 130. As this work of collecting milk and returning the empty churns is completed in the early part of the day, the vehicle is available for other duty, and actually his operating cost is about only 7d. per mile, say £3 15s. per week, which leaves a useful margin quite apart from whatever he may be able to earn from other work. There is sometimes reasonable profit on longerdistance 'work, with considerable opportunity for further employment of the vehicle in other fields. As an example, take another case, that of a haulier who has D48 a contract for carting 350 gallons of milk per day, which is apprcaimately a 2-ton load. The distance involved is 50 miles each way and the contract price is 2id. per gallon. His gross revenue on that basis is £25 10s. per week and his cost of operation for the 700 miles which the vehicle must run each week is £19. That figure includes an allowance of £2 per week, as in the previous example, for extra wages and provision for a spare vehicle when the need arises. A niodern, speedy, •pneumatic-tyred 2-ton vehicle can easily cover those 100 miles in the half-day, leaving it available in the afternoori for short-distance work. Actually I believe the contract involves early rising, and the milk delivery is done quite early in the day, so that with a second driver available it could do a lot of work: Alternatively, of course, in such a case as that just described it might be worth while to treat the vehicle gently in the balance of its spare time, using it for other duty on no more than two or three half-days of the week and allotting the balance to maintenance. It should not be forgotten, in this connection, that milk delivery involves high-speed running, and that factor makes it desirable to keep a closer eye upon the condition of the chassis generally than might otherwise be considered necessary. As a contrast and as a warning to those who might too rashly enter into contracts for carrying milk, I should like to refer to an example where such an entry was made and deeply re gretted. This was the case of the haulage of 1,000 gallons a day, 100 miles each way, the price paid being lid, per gallon. (Compare this with the 2id. for 50 miles, as in the previous example.) A 6-ton vehicle was used, and that, running 1,400 miles per week, involved an expenditure of l at least £53 Os. 8d. on bare operating cost, without any of that supplementary provision which I have shown to be of great importaace, indeed, vital. The revenue from this contract is only £43 15s. per week. At its inception one of my haulier friends asked my advice concerning the contract. I told-him to have nothing to do with it, and, fortunately for him, he took my advice.. A competitor accepted the price and in the course of about 18 months wet succeeded by somecue else and he, too, in another period of like duration, found himself unable to carry on. I believe that contract is again on offer. I sincerely hope that there will be no more takers. I feel sure that there will be none among my regular readers. S.T.R.