GOOD DESIGN ISTINGUISHES the ATLAS

Page 52

Page 53

Page 54

Page 55

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

Standard's Newcomer Gives Good Performance with 1 cwt. Overload : Manceuvrability and Easy Access to All Components Among its Strong Points

By Anthony Ellis

REMARKABLE manceuvrability and exceptional accessibility to the engine for servicing are the outstanding features of the Standard Atlas 10-12-cwt. van. It is the first goods vehicle to be produced ab initio by the Standard Motor Co., Ltd., for commercial purposes, previous _vans and pick-ups manufactured by the company having been direct derivations of existing private cars.

Although the engine, gearbox and rear axle are similar to those used in Standard cars, the remainder of the vehicle represents entirely new thinking.

At the time of its introduction last year, many people were surprised by the choice of a 948 c.c. engine to power a vehicle which had a maxi

mum recommended gross weight of 34 cwt., whereas the current trend is towards engines of about 11 litres for such an application. Any doubt which I may have entertained as to the ability of the 35 b.h.p. power unit to provide adequate performance was dispelled by the results obtained on test. Running 1 cwt. overloaded, the van accelerated from 0-30 m.p.h. in 15 seconds and yielded a maximum speed of more than 50 m.p.h.

The engine works fairly hard when the van is driven fast, and can be revved above 5,000 r.p.m. Experience gained with the unit in Standard 10 cars has shown that it is extremely sturdy and is capable of sustained high r.p.m. without risk of premature failure. It is slightly detuned for service in the Atlas, with the compression ratio lowered to 7 to 1 to allow operation on commercial grade petrol—the fuel used throughout the test.

Some indication of the quality of the engine is given by a recent arduous test run undertaken with a normal Atlas van from Cape Town to Gibraltar. The 10,000-mile trip included a crossing of the Sahara desert and was completed in 400 hours' driving time at an average speed of 22 m.p.h.

The vehicle was carrying a 12-cwt. payload for most of the trip, with an additional 2 cwt. of water and sand mats for the desert crossing. The engine is said to have behaved faultlessly throughout, returning an oil

consumption rate which was assessed at not less than 3,000 m.p.g.

For my road test the Atlas carried sand bags totalling 11 cwt. Combined with the passenger carried throughout the test, they brought the gross weight to 35 cwt. 1 qr., which was 1 cwt. 1 qr. above the recommended weight. Thus the payload capacity is about 10 cwt. if a passenger is carried or 12 cwt. with only the driver. Nearly even weight distribution was achieved with the test vehicle, which had 18 cwt. on the front axle and 17 cwt. 1 qr. on the rear.

As the van had completed only 336 miles when handed over to me, I attet.--..p.iP4 to run it in a little more before takii-,7 the acceleration an d fuelconsumption figures. Consequently, I conducted hill-starting and general handling tests first.

On Succombs Hill, Surrey, the Atlas made smooth restarts in first and reverse gear on the 1-in-5 section of this difficult incline. Farther up the hill it would not restart on a 1-in-4-} gradient near _ the summit. There seemed to be some loss of power at this point and the engine would not idle. The reason, I think, was that : gradient and steep camber of the id combined to alter the level of r..1 in the emulsion tube of the rburetter and thus made the mixture ) rich. Local journeys in and around London brought the mileage-recorder reading to over 500, at which point it seemed fair to take fuel-consumption figures. The seven six-mile runs which made up this test took place over the undulating stretch of the A6 road betweert Barton-in-the-Clay and Clophill. Each circuit consisted of two three-mile out-and-return legs.

Although not exceptional for vans running at the weight of the Atlas, the figures obtained were acceptable, varying from 29.92 m.p.g. non-stop under full load to 34.24 m.p.g. nonstop with no load. Here, again, the comparative newness of the running units probably forfeited 2-3 m.p.g.

During the tests with one stop per mile and four stops per mile, the vehicle was halted on each occasion for 15 seconds and the engine was left running. Easy restarts could be made in second gear, whilst the van reached 30 m.p.h. without trouble between quarter-mile stops.

When the ignition was switched off after each test run, the engine was noticed to run-on for about 10 seconds. Although this was the only time that this characteristic was apparent, it is annoying and I mentioned it to Standard's after the test.

It had apparently occurred on the prototype Atlas and an additional manually operated cut-off had been fitted in the inlet manifold to prevent it. Modifications to the induction system were thought to have cured the condition and the cut-off was omitted from production vehicles. I suggest that it should be restored.

Much of the engine's success must he attributed to the excellent fourspeed gearbox with which it is combined. Although the instruction book

suggests slow and deliberate movement of the gear lever to give best results, the synchromesh mechanism on second, third and fourth ratios proved to be almost unbeatable and was, in fact, so good that the clutch became nearly superfluous except when starting from rest. The gear-change was extraordinarily fast.

The gear lever, a cranked arm rising from the gearbox turret, is awkwardly placed behind the driver because of the rearward location of the gearbox. Even so, it is better than the steering-column gear levers which are often provided on vans of this type•

Useful Third Gear

Through-the-gears acceleration records were taken up to 40 m.p.h., the final figure for each increment of speed being the mean of runs in both directions on the same stretch of the North Orbital road. Rapid gearchanges and a well-chosen third gear which could be used up to just under 40 m.p.h. allowed this speed to be reached in 28.6 seconds.

For the direct-drive acceleration tests, top gear was engaged at about 6 m.p.h., showing commendable flexibility for a high-revving engine. From this speed the Atlas pulled away smoothly up to its maximum speed. At no point in the top-gear speed range was there any noticeable vibration or judder-a tribute to the three-point engine-gearbox mountings.

The use of I3-in, wheels necessitates the fitting of brake drum' of a smaller diameter than usual, which could affect braking performance adversely. However, t h e figures obtained on a surface which was not ideal-tarmacadam recovering from a coating of ice-showed that braking was in keeping with the general performance.

Good Brakes

Stops were made from 20 m.p.h. and 30 m.p.h. in both directions, the means of the stopping distances being 22 ft. and 46.5 ft. respectively. On each occasion the off-side rear wheel locked for over half the distance.

Situated under the full-width shelf below the dashboard, the hand brake is not particularly easy to reach. This position, however, has the advantage that the deep and useful shelf is left clear of encumbrances. Once reached. great purchase can be placed on the lever, and the system gave a Tapley reading of 25 per cent. when applied from 20 m.p.h.

Bison Hill, near Whipsnade. was chosen for the hill-climb tests. The ascent was made in three minutes and, although on one section the gradient is 1 in 6, the lowest gear employed

was second, which was in use for 1 minute 18 seconds and the minimum speed was 11 m.p.h. This is a good performance for a vehicle with a power-gross-weight ratio of under 1 h.h.p. per cwt.

At an ambient temperature of 38° F., the radiator temperature at the bottom of the hill was 146" F. and it rose after the climb to 165 F., showing that the pressurized cooling system caters for arduous operation

To assess fade the van was coasted [own the hill in neutral with the foot 'rake applied to keep the speed down a 20 m.p.h. As the gradient flattened .ut, top gear was engaged and full irottle applied against the brakes to laintain the same speed. The descent ccupied 2 minutes 53 seconds, of ihich time 28 seconds were spent in op gear.

A full-pressure stop from 20 m.p.h. t the bottom of the hill produced a eading on the Tapley meter of 58 per ent., which, when compared with the eading of 71.5 per cent, taken earlier I the day from the same speed with ooi brake drums, showed that fade /as not severe.

Throughout the tests the Atlas was lost pleasant to drive and had an xcellent main-road performance. Its laximurn speed of more than 0 m.p.h. allowed it to be cruised at n easy 40-45 m.p.h., at which speed ngine noise was not obtrusive.

Excellent Maneuvrability However, the van really comes into s own in towns, where its remarkble steering lock can be used to full dvantage. The turning circle between erbs is only 29 ft. This is achieved -minty by employing a narrow track or the front wheels.

The recirculating ball steering quires less effort than is often ceded in vans which carry at least alf their total weight on the front 'heels. In towns the Atlas is easier ) drive and—even more important-) park than most small cars and -cwt. vans.

Any increase in roll which might ave arisen from the narrow front .ack is checked by a novel frontispension layout which has preiously been employed on some icing cars because of its built-in ati-roll characteristics. Independent ub-axles are carried on wishbones Id a transverse leaf spring is used as te resilient member.

This spring is mounted on a central ivot which allows it to check roll in iuch the same way as an anti-roll ar. Damping at the front is by lescopic shock absorbers mounted side the wishbones. The rear axle carried conventionally on semiliptic springs, the front and rear )mbination giving a well-sprung ranee ride. As with all light slab-sided ins, the Atlas is sensitive to side inds, but any deviation from course in be corrected quickly by the :curate steering system.

I was impressed by the attention hich has been paid to driver cornrt. The identical seats for both iver and passenger are comfortable ough simple. The positions of the pedals are good, but some form of rest below the accelerator would be appreciated.

Oddly, the steering column is inclined inwards towards the centre line of the vehicle. This tilts the steering wheel and tends to make one's hands adopt a "twenty to two" attitude.

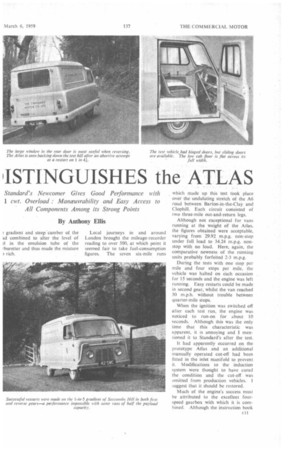

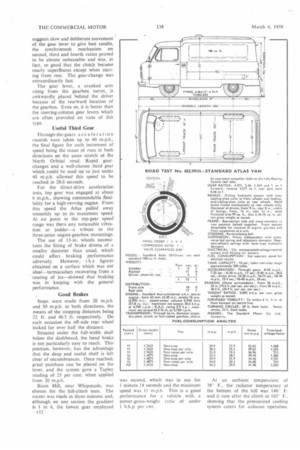

Visibility, as on all the forwardcontrol vans at present in production, is excellent and there is a large window in the rear door to assist the driver when reversing.

The version of the Atlas which tested had hinged cab doors, although sliding doors are available. They are wide and, combined with the low floor line provided by the 13-in. wheels, make for easy access to both seats.

The rear door is also wide, but as it does not have cranked hinges it cannot be opened through 180° or 270° to permit the vehicle to be backed up close to a loading bay.

A good interior light illuminates both the cab and the body. A ventilator in the roof effectively solves the problem of condensation inside the body and, in conjunction with an excellent Smith's heater which is a production option and was fitted to the test vehicle, provides pleasant fresh-air heating.

As the air duct for the radiator is beneath the cab, the floor line across the full width of the cab can be made fiat, so that it is easy to reach the driver's seat from the near side.

Easy Servicing

Close attention has been paid in the design to good accessibility to all components, with emphasis on the engine. To this end, the chassis frame is constructed in halves bolted together. The front half can be unbolted and. with the engine, gearbox and front suspension, can be detached as a unit for servicing.

I did not carry out this operation, but I am assured by Standard's service department that by this means it is possible to make an engine change in eight man-hours.

There is ample space around the engine and two sections of the cowl on each side, secured by two bolts mating with caged nuts, may be removed to give clear access to both sides of the unit.

Beginning the maintenance tests, the engine cowl, which is secured by one spring clip, was removed in 7 seconds, following which I checked the water level in the cooling system in a further 5 seconds. The dipstick is longer than normal to allow it to be brought up level with the top of the engine and in this position it is easy to reach, so that I was able to check the oil level in 18 seconds.

Mounted on the near side of the engine, the distributor presents no difficulties in servicing. I checked the gap between the -points with the detachable cowl section in place. My time of 2 minutes 4 seconds for this operation included removal of the starting handle from its mounting across the passenger's foot-well and replacing it, although I had an assistant to rotate the engine.

To take out the sparking plugs it was necessary to remove the passenger's seat and the near-side cowl section. The plugs were removed in 3f minutes and replaced complete with the cowling and seat in 4 minutes 22 seconds.

Although located low down on the near side of the engine, the gauze in the petrol pump was taken out, cleaned and replaced in 1 minute 19 seconds.

Neat Battery Mounting

The battery is located behind the passenger's seat and is secured by two wing nuts which hold down a channelsection member over the vent plugs. This member acts as an airtight seal over the plugs and vents to atmosphere through a rubber pipe which emerges below the floor. Two minutes 36 seconds sufficed to inspect the level of the six battery cells.

On the opposite side of the cab is the spare wheel, which is attached to the bulkhead. I removed it in 21 seconds, 9 seconds of which was oecupied in detaching the driver's seat, and replaced it in I minute40 seconds, the seat taking 30 seconds to refix.

The same spanner could be used in inspecting the gearbox and rear-axle oil levels, these operations being carried out in 20 seconds and 34 seconds respectively.

An efficient ratchet-type screw jack supplied in the tool kit enabled me to adjust the front brakes (which have two back-plate-mounted adjusters at each drum) in 7 minutes, jacking up each wheel independently. I spent 44minutes on the single adjusters on the rear brakes, the time for the complete operation being 114 minutes.

The front grille can be removed by undoing two Dzuz fasteners, to reveal the reservoir for the hydraulic brake and clutch systems. Removal and replacement of the grille took 26 seconds, and inspection of the hydraulic fluid level, 9 seconds.

These sample tasks show that the Atlas will be exceptionally easy to service both on routine occasions and on comprehensive overhauls.