Superheated Steam : Article No. I.

Page 2

Page 3

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

By David J. Smith.

In large stationary steam-engine practice it is recognised by all engineers that the only method by which the steam engine can be made to compare with, if not to exceed, the economical results given by the internal-combustion engine is by the use of superheated steam. Existing plants are constantly being converted to its use, with the result that not only is their output greatly increased, but the fuel consumption is very largely reduced. In view of these well-known facts, it is strange that the designers of steam commercial motors do not pay more attention to the use of superheated steam, as at present there is not, as far as the writer is aware, a single Britishbuilt vehicle in which superheated steam is employed. On several vehicles a small superheater is fitted, which is called by the manufacturer a steam drier; this is not, however, fitted with any idea of getting any material advantage from superheating, but in order partially to dry the very wet steam that most small wateror fire-tube boilers yield. The poor results obtained by the few who have built commercial vehicles to use superheated steam, have perhaps had a deterrent effect on manufacturers, although, in steam pleasure car work, the reverse is the case, the cars not using superheated steam having completely disappeared, they haying proved unable to compete in any way with their rivals. A short review of what has been done by, and the cause of the failures of, those who have attempted to apply super. heated steam to commercial motors will, perhaps, prove interesting to many who are now considering the matter, and may prevent the same errors being again committed. It is quite certain that superheated steam was in use by many engineers who had no idea of its advantages, and, moreover, were actually hampered by it in the early days, the superheat not being obtained by express design, but simply by the method of obtaining the steam. The earliest application of superheated steam as a motive power dates back to about 1780, and it was also the first appearance of the flash boiler, which has revolutionised the pleasure steam cat. The apparatus was built in connection with an old Newcomen pumping engine. A pump, worked from the rocking beam of the engine, delivered a fixed quantity of water per stroke into two heavy cast-iron tubes placed horizontally -over a furnace. This steam was, of course, highly superheated, as the tubes were kept red hot, but why this type of boiler was chosen, when superheat was not desired, is not known. A very similar plant was installed in one of the first steamboats, but no record remains of the ultimate result. In 1824, T. Burstall made a steam omnibus, or coach, fitted with a flash boiler made of cast-iron. The boiler, it is stated, gave a great deal of trouble, and this is not to be wondered at, considering that it was of rectangular shape, and the water was fed to the boiler by air, pressure pumped into the water tank. The use of superheated steam must, in these days, have been attended by insuperable obstacles in the matters of lubrication and packing of the cylinder glands. Jacob Perkins used coil boilers, and worked his engines at astonishing pressures, but there is no record that he attached any value to superheat, or had any troubles from it, though his vehicles were all, for that period, very successful.

There is no evidence of superheated steam being used on any road vehicle after this until after the passing of the emancipation Act of 1896. Two firms then started to manufacture motor lorries with the idea of using superheated steam, the advantages of which had, by this time, become well-known from its performances on stationary plants. These vehicles, known, respectively, as the Musker and the Simpson and Bodman, were very different in design. The Simpson lorry had a flash boiler mounted on the front in the usual position. This boiler was of peculiar design, and its tubes were on the Row indented system. The tubes were connected together at each end by horseshoe-shaped bends in such a manner as to form one continuous coil, The boiler was heated by coke. These twisted or indented boiler tubes had already been tried and abandoned by Serpollet on his pleasure cars, as it was found that, when the tubes got very hot, and the pressure high, the tubes had their indentations blown out ; they thus became circular,

stretched very thin, and, then burst. As a coke lire cannot be regulated with the facility of an oil-fired furnace, there is no doubt that this must have happened with the Simpson boiler, as no water was ever in the boiler when the vehicle was standing. Each rear wheel was driven by a separate three-cylinder, single-acting engine, the cylinders being set at 120 degrees round one crank. By this means the differential gear was dispensed with, a doubtful advantage, considering the multiplication of joints, etc., entailed by two separate engines.

The Musker lorry was practically an attempt to convert the existing lorries into a motor vehicle, as all the machinery was slung under the platform on a separate frame. The boiler was a flash one, and consisted of concentric coils, laid horizontally in a strong asbestos-lined case. An oil 'burner, in which common oil was used on the spray system, was fixed at one end, and the flue was at the other end, and directed towards the ground. A separate small engine drove a fan to supply air for combustion and oil to the boiler. In some of these lorries this engine also drove the feed-pump to the boiler. This small engine was automatically stopped and started by the boiler pressure acting on a diaphragm valve. The feed-water to the boiler was under separate control; a thermostat in the steam pipe reducing the supply of water to the boiler if the temperature of the steam fell below a certain point. Heavy oil or spray burners have been very unsatisfactory when applied to motor vehicles, and, no doubt, this, coupled with the failure of the automatic devices, had a great deal to do with the non-success of the Musker vehicle.

No mention has been made of the systems which have proved so successful in light steam car work, viz., those of Serpollet, Miesse and White, as, with the exception of Serpollet, nothing has been done in the commercial line by the other makers beyond fitting a light van body to one of the ordinary steam car chassis. The Serpollet system has remained unaltered for the last eight years, and, from its recent successes in motor-omnibus work, promises soon to become very prominent. It consists of a flash boiler, heated by a multi-jet burner of the Hecla or Swedish type, which burns common paraffin. Driven either off the main engine, or by a separate small engine, is the combined water and oil pump, which is the key to the whole system. These pumps are so regulated that they deliver water and oil, in fixed proportions, to the burner and boiler, so that, no matter what the demand is on the boiler, the steam is delivered superheated to the desired extent, and the boiler is not damaged by overheating. Having noted what has been done in the application of superheated steam to motor vehicles, it may be as well to enquire what are the advantages possessed by superheated steam that make it so desirable where economy is concerned and small but efficient plants ar-3 required.

A small, simple, high-pressure engine, using saturated steam, takes about 361b. of steam per h.p. per hour, and even on larger steam plants, with compound engines, the consumption is seldom under 171b. per h.p. By superheating the steam, say, to 7oo or 800° Fahr., the consumption, even with a small engine of 3 or 4h.p., can be reduced to 111b. per h.p. This means that not only is a great economy of fuel obtained, but a much smaller boiler can be used, and much less water need be carried, or the same quantity of water will go much further. Condensation is also entirely abolished. All these are valuable points on a motor vehicle, and these advantages would alone make superheated steam much to be desired. There are, however, others, which are less understood. If a small steam engine be taken for the purpose of experiment, and supplieu with ordinary wet steam at 2oolb. pressure, a certain maximum h.p. can be obtained. Without increasing the pressure, but by superheating the steam, the power can be greatly increased, and will continue to increase with the growing superheat until the limit of lubrication temperature is reached. The engine will, therefore, be giving off a greatly increased power, for probably onethird of the steam consumption on saturated steam. This enables a very small engine to be used, and so reduces the weight of the machinery. Taking into account the reduction that can be made in the weight of the engine, boiler, water and fuel tanks, it is possible to save quite so per cent. by using such a plant of the weight of one of similar power but using saturated steam.

It is often thought that steam of a high pressure must needs be superheated. This, of course, does not follow at all. Steam at 200lb. is, obviously., at a much higher temperature than steam at molb., but both may be wet, whereas steam at 11b. pressure can be superheated to 1,000° if desired, and its pressure will not increase if it is free to expand. Superheated steam is, therefore, very easily condensed, as a certain volume of superheated steam may only contain one quarter the weight of water in an equal volume of saturated steam. When the steam is supplied from a flash boiler it may be condensed and returned, and so used over and over again, as the oil contained in it is no drawback in a flash boiler. A great reduction in the quantity of steam required per h.p. naturally means a corresponding saving in fuel. A test recently taken of a small superheated steam plant on a car showed that tb.h.p. for one hour could be obtained from .81b. of fuel. This compares very favourably with any of the internal-combustion engines fitted on motor vehicles, and even better results could be obtained.

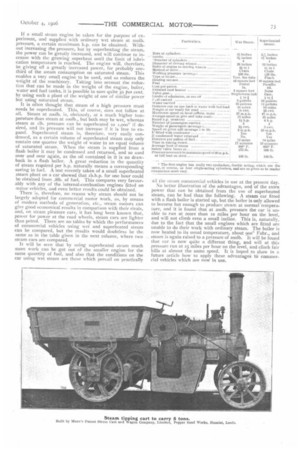

There is, therefore, no reason why steam should not be largely adopted for commercial motor work, as, by means of modern methods of generation, etc., steam motors can give good economical results in comparison with their rivals, and, on steam pleasure cars, it has long been known that, power for power at the road wheels, steam cars are lighter than petrol. There are no tables by which the performances of commercial vehicles using wet and superheated steam can be compared, but the results would doubtless be the same as in the table given in the next column, where two steam cars are compared.

It will be seen that by using superheated steam much more work can be got out of the smaller engine for the same quantity of fuel, and also that the conditions on the car using wet steam are those which prevail on practically all the steam commercial vehicles in use at the present day. No better illustration of the advantages, and of the extra power that can be obtained from the use of superheated steam, can be had than the following. A steam car fitted with a flash boiler is started up, but the boiler is only allowed to become hot enough to produce steam at normal temperature, and it is found that at 200lb. pressure the car is unable to run at more than to miles per hour on the level, and will not climb even a small incline. This is, naturally, due to the fact that the small engines which are fitted are unable to do their work with ordinary steam. The boiler is now heated to its usual temperature, about goo° Fahr., and steam is again raised to a pressure of 2oolb. It will be found that car is now quite a different thing, and will at this pressure run at 25 miles per hour on the level, and climb fair hills at almost the same speed. It is hoped to show in a future article how to apply these advantages to commercial vehicles which are now in use.